Climate change conversations seem to come with invisible boundaries: humanists talking with humanists, scientists talking with scientists. In some conversations, climate change can be just as taboo as religion, sex and politics.

But how do you tackle a problem you can’t talk about?

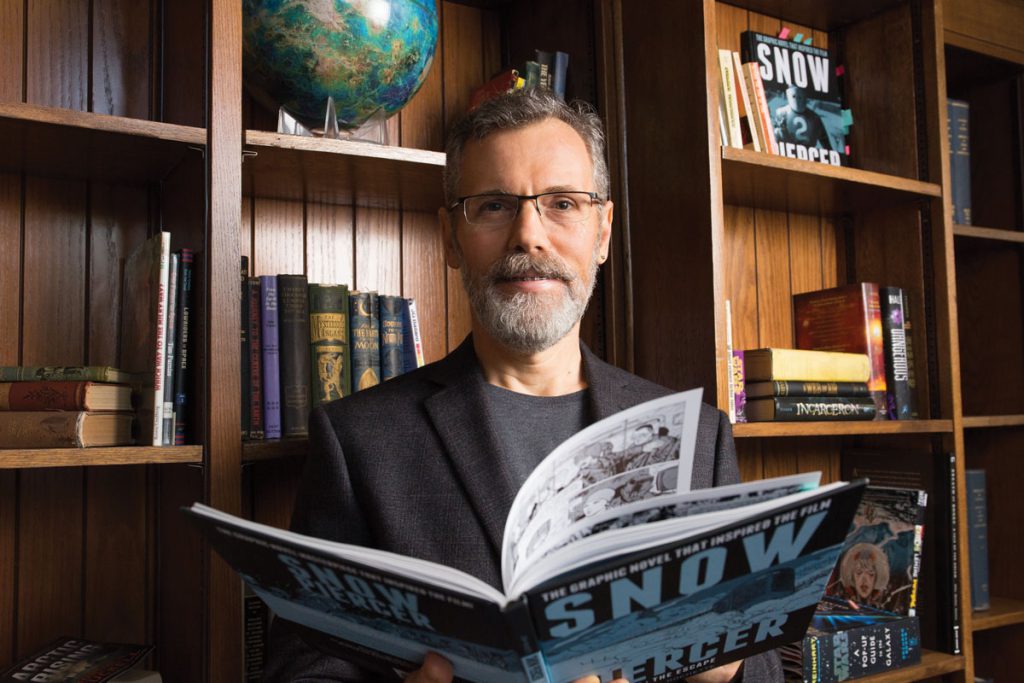

University of Florida science fiction scholar Terry Harpold wondered if humanists and scientists could collaborate on an unorthodox conversation that could alter the discourse on climate change. He brainstormed with Alioune Sow, director of the France-Florida Research Institute, and an idea took shape.

He called geochemist Andrea Dutton, who had just released a study on sea level rise, with a proposal. If he and Sow could get sci-fi novelists to participate in a panel discussion, would she be the voice for science?

“It was out of the blue,” says Dutton, an expert on earth’s climate archives, going back millions of years.

Dutton had noticed the same phenomenon: a science conversation going on in the journals, a literary conversation taking place in books and movies, and a public conversation full of dissonance. She signed on.

The experiment took shape as a yearlong symposium series, “Imagining Climate Change: Science and Fiction in Dialogue.” The first symposium was in October 2015 with another in February and a March screening of a climate change science fiction film. The series was funded by the French Embassy of the United States, the France-Florida Research Institute and a half-dozen departments in UF’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. The scope has been international, including scientists and sci-fi authors from France, the Caribbean and the United States and the filmmaker, Wanuri Kahiu, from Kenya.

To Harpold, “Imagining Climate Change” is an invitation to look into the future. As a scholar of science fiction, literary worlds that don’t exist don’t faze him. The scary thing, Harpold says, is those worlds look less and less like fiction.

“This is an opportunity to talk about how changing the climate changes the human world in every imaginable way.”

Harpold says once the scientists and authors got started, the conversations spilled into hallways and persisted through language barriers. One night at dinner, he noticed that UF entomologist Andrea Lucky had been deep in conversation with Jeff VanderMeer, author of “Annihilation,” for 45 minutes nonstop.

“That was an interdisciplinary moment,” Harpold says. “That’s the conversation I wanted to happen.”

As far as Harpold knows, “Imagining Climate Change” is unique, and he thinks there is no better place for the program than UF.

“Where else would it start? We’re a land-, sea- and space-grant institution with superb students, superb faculty,” Harpold says. “We have an obligation as scholars and as educators — frankly, also as human beings — to be part of this conversation.”

Harpold drew students into the conversation with Climate Fiction, a spring undergraduate course. Steeped in ecological sci-fi, the students read nine books that took them into a sometimes hopeful, sometimes dystopian future, among them 1962’s “Drowned World,” by J. G. Ballard, in which London is under water. In the book, humans adapt to the changed environment by changing, too, at a cellular level.

“We don’t worry about whether Ballard gets the science wrong,” Harpold says. “What we worry about is what Ballard can tell us about a human life that is transformed by living in a transformed climate, what it means to be human in a place where things have changed so fundamentally that you can no longer continue to live the way you did.”

The science fiction boom in the 20th century, with the advent of the space program and visions of aliens and outer space, is fostering a different thought experiment for the 21st century as eco-disasters replace alien invasions.

Unlike scientists, writers can speculate. What are the logical outcomes of the data presented by science? Emotional narrative is not the currency of science, Harpold says, but it may be the “currency that will reach people, to get them to think about whether they want to live in a world that looks like that.”

UF President Kent Fuchs spoke at the spring symposium and noted that collaborations of scientists and humanists offer hope: “Scientists can illuminate a great deal about Earth’s environment and its changes. They can help quantify our impact and provide wisdom on scientific solutions. But they cannot change our hearts.

“Artists,” he said, “can move us.”

“Imagining Climate Change” will continue into next year. Harpold is in discussion with the Center for European Studies to bring in French and German ecologists in the fall, and eventually he hopes to invite researchers, writers and artists from South America, Africa and Asia to participate. He has petitioned to make Climate Fiction a permanent course offering, and hopes the symposia become the impetus for a research unit for climate and the humanities and perhaps even a research program for doctoral students, hence seeding the future with climate scholars. The focus will remain international; climate change knows no borders.

“Climate change challenges the disciplinary boundaries we believe to be stable,” Harpold says. “There’s no end to this, no end to what this means for all of us.”

UF’s breadth of teaching and research, Harpold says, gives it particular relevance for the conversation between the sciences and the humanities.

“We can create widgets, develop information, write books, edit journals, teach classes, but did we do good while we were here?” Harpold says. “At a place like UF, we have the potential to make a new kind of conversation happen about the most important thing we need to do good about.

“We have the luxury of thinking big,” Harpold says. “Let’s do that.”

Source:

- Terry Harpold, Associate Professor of English

Related Websites:

This article was originally featured in the Summer 2016 issue of Explore Magazine.