Geography lecturer Gabriela Hamerlinck debuted a new class for Fall 2019: Pandemics. As the semester began, she was lecturing about history – the plagues of prehistory and the Black Death.

By the end of the semester, current events were about to catch up with her lesson plan. And as she began spring semester, teaching People and Plagues, the headlines could not be ignored.

“We sort of scrapped the syllabus for a while and focused on the coronavirus,” says Hamerlinck, whose specialty is medical geography. “I wanted my students to see and apply what they were learning to this real-life scenario. It’s great timing for teaching, although I’d rather not have that great timing.”

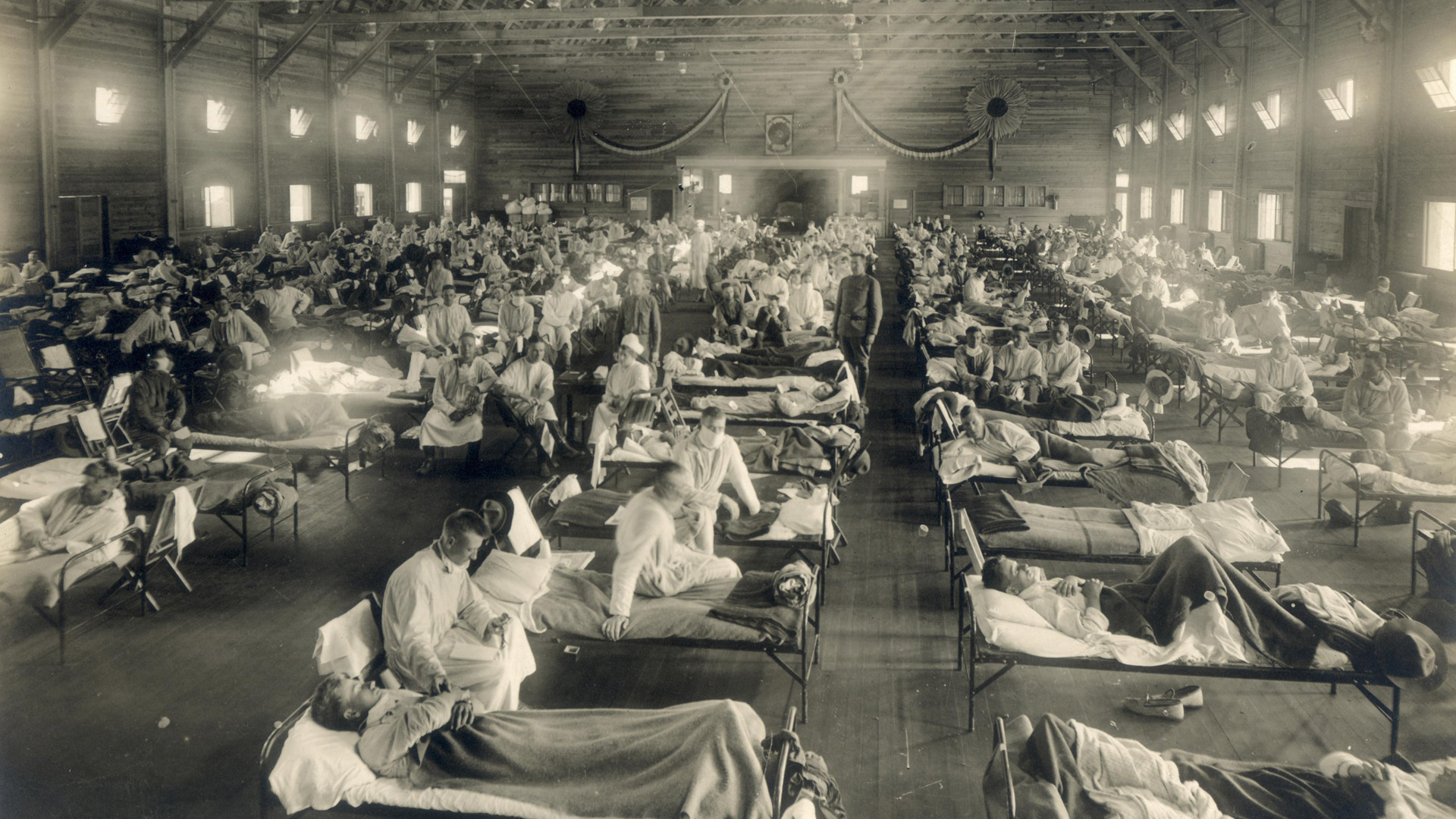

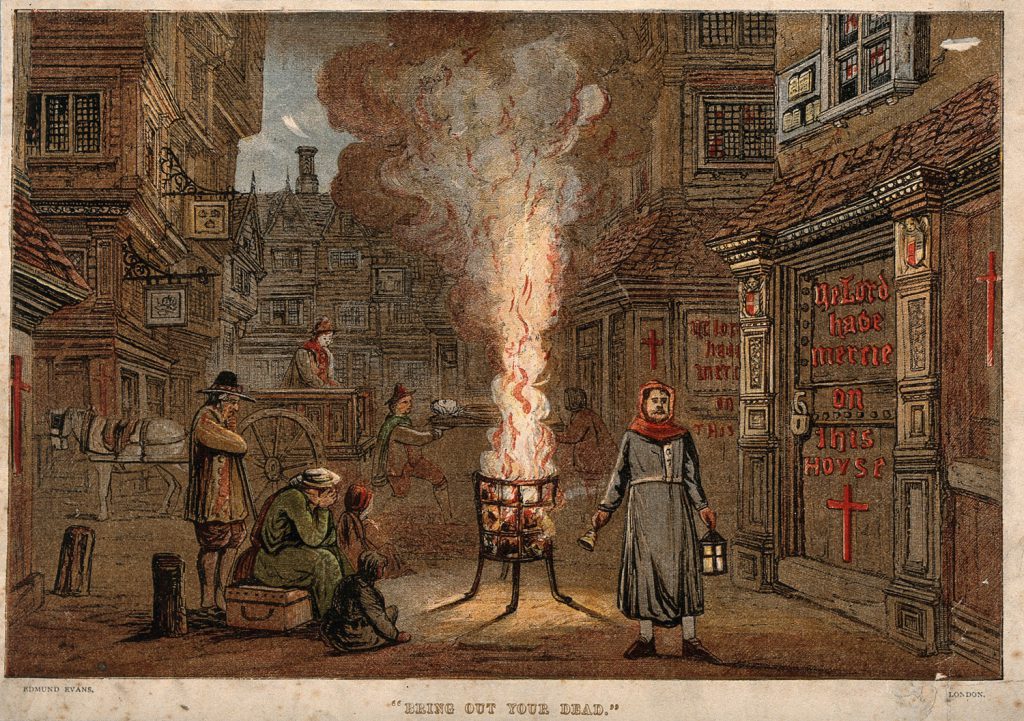

The history of pandemics and plagues is long. There is evidence of a plague in 3000 BCE in a mass grave in a village in China on a site that was not inhabited again. Europe struggled with the Black Death in the 1300s, with half its population wiped out. The Black Death appeared again in the 1600s. Europeans brought diseases with them to the New World, killing 90 percent of indigenous populations in the Western Hemisphere. In more modern times, the Spanish Flu of 1918 is estimated to have killed 50-100 million people, and from 1981 to the present, HIV/AIDS has claimed 35 million lives.

We sort of scrapped the syllabus for a while and focused on the coronavirus…It’s great timing for teaching, although I’d rather not have that great timing.”

Gabriela Hamerlinck, UF Geography lecturer

Hamerlinck says several factors determine whether an outbreak, a small-scale incidence of disease, blossoms into an epidemic, a larger scale outbreak with incidence of disease beyond a normal threshold level. And then there are pandemics, which sweep over the world.

“Reaching a pandemic level is terrifying,” Hamerlinck says.

Modern life and life in bygone days share some factors that lead to pandemics. But modernity has magnified those factors and added a few.

“There’s just a lot more disease risks that exist nowadays,” Hamerlinck says.

Society is more mobile, people travel more for work and pleasure, world population is growing, sending humans into formerly wild habitat where they can encounter novel pathogens, and then there’s climate change. The stage is set, it seems, for a pandemic.

Mobility and Globalization

Mobility and risk go hand in hand, both in historic and modern pandemics. Hamerlinck teaches about the Mongol hordes, who spread the plague along the Silk Road, a 7,000-mile trading route between Asia and Europe. Modern times have hordes as well, and modern hordes have speed on their side.

“You can track the progression of the plague based on where the Mongol hordes were,” Hamerlinck says. “Nowadays, spring breakers in Florida are all coming from different locations. When they go home, they just jump on a plane and they can be halfway around the world in a day, before they are showing signs and symptoms of being ill.

“All things considered, it is quite easy for diseases to spread globally really quickly,” Hamerlinck says.

Housing vs. Habitat

The global population today is larger with more people crowded into more mega cities and in closer proximity, making it easier for disease to spread. The growing population also means humans are encroaching more than ever on new environments, creating pastures and farmland where once there were few humans. The wild animals encroached upon, in some cases, are reservoirs of disease.

For sophomore Brian Branstetter, who took both Pandemics in the Fall and People and Plagues in the Spring, the unit on HIV/AIDS resonated most.

“For me, the week that made it real was when we learned about HIV and AIDS,” Branstetter says. “The prejudice, the way humans handled the disease, allowed it to be spread globally and made it such a huge issue. And it’s still with us, so we all understood the magnitude of it and how it’s killed millions of people.”

Branstetter also said he was struck by the fact that HIV/AIDS jumped from chimpanzees to humans not once but seven different times before it went from a zoonotic disease – transmitted from animals to humans – to an anthronotic disease – transmitted human to human. The original reservoir is unknown but is thought to be bats, which may be the source of other diseases, such as the Ebola epidemic in 2014-16 in West Africa, and perhaps coronavirus.

For me, the week that made it real was when we learned about HIV and AIDS. The prejudice, the way humans handled the disease, allowed it to be spread globally and made it such a huge issue.

Brian Branstetter, UF Sophomore

Mosquitoes also serve as vectors for disease, biting an animal that carries a disease and transmitting it to humans with a bite. Zika, yellow fever, dengue and malaria are all vector-borne diseases.

Hamerlinck says the class discusses which pathogens are involved – bacteria, viruses, parasites – and which hosts are involved, such as bats, birds or chimpanzees.

“If a disease jumps into human populations because it is spilling over from an animal population, what factors might have influenced that jump?” Hamerlinck asks.

For zoonotic diseases, human actions play a role. Diseases jump from animals to humans when humans encroach into formerly wild areas and when humans fail to observe proper hygiene in butchering or marketing meat from animals.

Climate Change

As the climate shifts, risk of pandemic disease could shift as well.

Humidity, rainfall, temperature and other environmental factors affect the range of animals, a warmer world potentially changing or increasing the range of tropical creatures and the diseases they carry, as well as the range of the mosquitoes, parasites or pathogens that can transmit the disease to humans.

“The disease vectors – mosquitoes, ticks, lice, etc. – could expand or shift their range and may move into locations where human populations have not expected them and where there is not a healthcare infrastructure to deal with them,” Hamerlinck says.

Hamerlinck asks students to engage in scenario planning, figuring out where to devote their public health dollars as they learn about new public health threats week by week. Often, she says, students choose to devote their budget to diseases that threaten human populations right now.

“The future threat doesn’t feel strong enough, like something to be worried about yet,” Hamerlinck says.

What changes that? Talking about coronavirus. The current pandemic, she says, has more students thinking about public health measures with a main focus on research and education.

What’s Next

One way Hamerlinck gets the students to think more about their public health budget is by talking about Nipah virus infections, which can be asymptomatic, cause acute respiratory distress, or cause even fatal encephalitis.

“I ask them, ‘do you think we should be worried about this disease?’” Hamerlinck says.

Like Ebola, Nipah is a devastating hemorrhagic disease. The fatality rate is 40 to 75 percent, according to the World Health Organization.

“It hasn’t really jumped into the human population yet,” says Hamerlinck, adding again, “Yet.”

As a viral hemorrhagic fever, Nipah and Ebola have a bigger dread factor and are more exotic than a respiratory disease with similarities to the flu, a familiar seasonal affliction, though deadly as well. The global attention to the Ebola outbreak in sub-Saharan Africa was more immediate and focused.

“You could see the difference in response to the shock and awe of a hemorrhagic disease vs. something that presents like the flu,” Hamerlinck says.

Flu season gives Hamerlinck a chance each year to talk about proper hygiene to prevent the spread of viruses and bacteria. Viruses are in the limelight lately but are no better or worse than bacteria or other pathogens, just different threats. With bacteria, antibiotics have kept diseases in check, but increasing antibiotic resistance could change that and already likely play a role in epidemics of tuberculosis around the world.

And tuberculosis isn’t the only disease threat, Hamerlinck points out.

There is a massive dengue outbreak in the Philippines, a cholera outbreak in Yemen, another Ebola outbreak in sub-Saharan Africa. Polio eradication efforts in Afghanistan have been put on hold to deal with the coronavirus.

“There are worldwide impacts beyond just people being sick with coronavirus right now,” Hamerlinck says.

Hamerlinck will have plenty of new material for the syllabus for the next semester of Pandemics.

“There are lessons learned from previous pandemics, so I’m really curious to see what happens when we come out of the coronavirus lockdown that we’re on right now,” Hamerlinck says.

And when she teaches the class again, it will get a new name: The Next Pandemic.

Sources:

Gabriela Hamerlinck, UF Geography Lecturer on Pandemics

History of Pandemics and Plagues

| Year | Description |

|---|---|

| c.3000 BCE | Prehistoric epidemic, village in China, mass grave, site not inhabited again. |

| 430 BCE | Plague of Athens – 100,000 victims, possibly caused by smallpox or measles. |

| 541 AD | Plague of Justinian – Bubonic plague that continued off and on for 200 years, killing as much as 10% of the world population. |

| 1346–1353 | Black Death – Spread along trade routes from Asia to Europe, killing about half of the European population. Spread by fleas on rodents. This pandemic led to the end of serfdom. |

| 1519–1548 | Mexico, Central America – Spanish carry smallpox to a native population of about 25 million. In the next century, fewer than 2 million survive smallpox and other communicable diseases. |

| 16th Cent. | American Plagues – Eurasian diseases brought to North America are estimated to have killed 20 million Native Americans. |

| 1665–1666 | Great Plague of London – Black Death’s last outbreak, 100,000 victims, including 15 percent of the population of London. |

| 1720–1723 | Great Plague of Marseille – About 100,000 people died. |

| 1770–1772 | Russian Plague – About 100,000 victims. |

| 1793 | Yellow Fever in Philadelphia – A mosquito-borne disease with 5,000 deaths. |

| 1860 | Modern Plague – Kills more than 12 million people in China, India and Hong Kong, until a vaccine is created in 1890. |

| 1889–1890 | Flu pandemic – 1 million people. |

| 1918–1920 | Spanish Flu – 500 million sick, about one-fifth died. |

| 1952 | Polio peaks. Vaccine is developed in 1954. About 60,000 children were infected. The last polio case in US was in 1979. |

| 1957–1958 | Asian Flu – Started in China, 1 million died globally. |

| 1981–present | AIDS – 35 million lives. Likely HIV jumped from chimpanzees into humans. |

| 2003 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, SARS, identified in China, causing 8,000 cases and 774 deaths. |

| 2010 | Haiti – A cholera epidemic killed 10,000 after a deadly earthquake. |

| 2009-2010 | H1N1 – Originated in Mexico. Infected as many as 1.4 billion and killed between 151,000 and 575,000. |

| 2014–2016 | Ebola – 11,325 deaths. Virus may have originated in bats. |

| 2015–present | Zika – virus spread by mosquitoes, causes birth defects. |

Lesson plans tap into pop culture

By the end of a semester studying contagious diseases, Hamerlinck says students need a break. Bring on the zombies.

Hamerlinck says zombies are a perfect fit in talking about pandemics, and several scientific papers use zombies in modeling.

“It’s an interesting way to think about hard choices,” Hamerlinck says. “Do you kill all the zombies to save the people who are still human? Do you try to come up with a vaccine? If you do, how do you distribute it? What if there is a lag between being bit by a zombie and becoming a zombie?”

Hamerlinck also reached into popular culture in another way that seemed fitting, say sophomore Brian Branstetter and freshman Lylybell Yanghua Zhou. Just as news about coronavirus was starting to take over the news cycle in the third week of January, the class viewed “Contagion,” a movie about a respiratory virus that causes a pandemic.

“We watched ‘Contagion,’ and later that day I took a nap back in my apartment, and when I woke up I saw on news feeds on my phone breaking news about coronavirus in China,” Branstetter says. “I thought I was dreaming at first because the similarities between the movie and what was actually happening were really, really strange.”

Zhou says her reaction as the lessons ticked by was “this is really happening.” She used to visit Hamerlinck’s office hours in Turlington Hall frequently, and when students left campus in March, she continued to reach out to discuss the news, eager to apply what she had learned to the headlines she was reading. Both Zhou and Branstetter say they now want to study epidemiology.

Hamerlinck says other students have reached out as well.

“They’re worried but also really grateful for what they’ve learned,” Hamerlinck says. “They’re actually realizing that they can put their classwork to use right now.”