In fall 2008, a homeowner in Pasco County was jailed for breaking the rules in his deed-restricted subdivision. His lawn was brown.

A few months later, spring 2009, Tampa Bay Water drained its 15-billion-gallon reservoir and crossed its fingers for an early rainy season.

This irony — jailing someone for not using water in the face of a water crisis — is something Florida will need to come to grips with in the face of the double whammy a changing climate and a burgeoning population represents, says Pierce Jones, who heads the University of Florida’s Program for Resource Efficient Communities, a research and extension program that supports green building and has worked with communities such as Celebration, near Disney.

Anyone who has lived in Florida for a minute and a half has seen the business-as-usual model of development. Bulldoze a parcel, build a big house on a big suburban lot, throw in a golf course, pave some roads and move on to the next parcel. That model has a carbon footprint the size of Godzilla, according to Jones, who got the opportunity to measure the conventional development model against a resource-efficient model a few years ago.

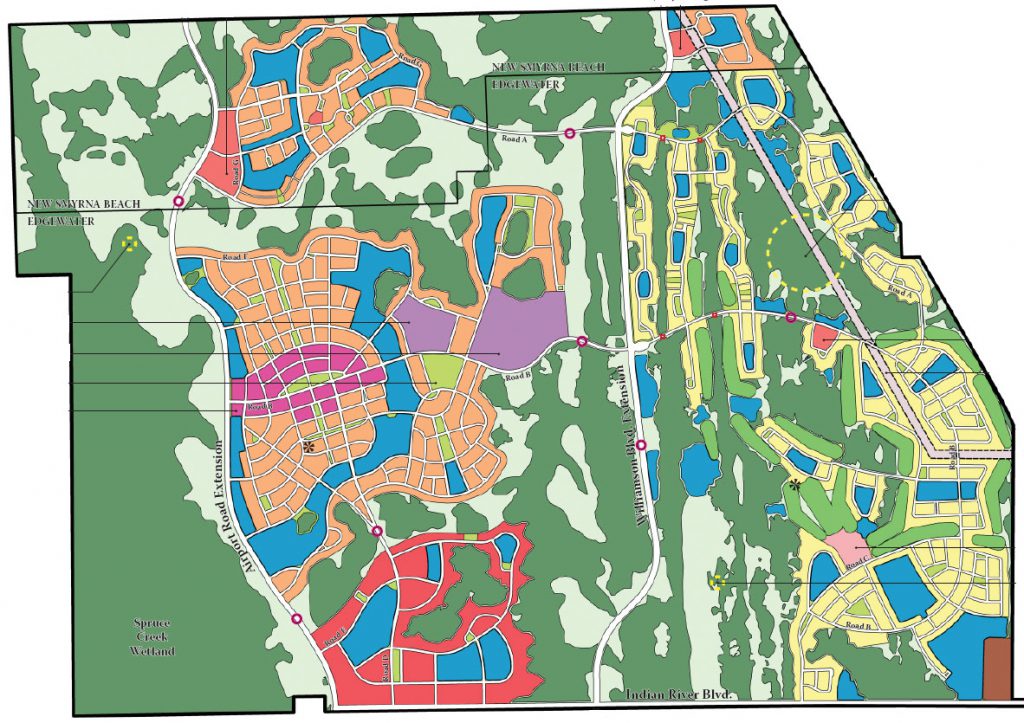

The developer of Restoration, a 5,187-acre master planned community in Volusia County, approached the Program for Resource Efficient Communities for help in 2006 during a review by the East Central Florida Regional Planning Council. Jones took a look and found a plan for 8,500 homes along with a golf course and suburban-style streets — all in the watershed of Spruce Creek, designated an Outstanding Florida Water for its high water quality.

“This was a standard product, standard Florida practice,” Jones says. “I looked at it and knew right away what the problem was — typical Florida sprawl.”

Jones suggested a more compact design and mixed uses — which also saved the developer money — and project designer Brian Canin delivered a new design that could be the poster child for more sustainable development.

“The golf course was gone, the roadway system almost cut in half, two-thirds of the land was in conservation,” Jones says. “But even better, it gave us two fully developed designs — a before and an after — and we could quantify the differences between conventional subdivision design and green subdivision design.”

Road building and maintenance have a huge carbon load. Building a road requires mining materials, transporting them, shaping them into a road, establishing and maintaining rights of way, and at some point in the future, rebuilding. The 2009 redesign cut lane miles from 186 to 103, potentially saving the developer $145 million in road-building costs and keeping 5,855 metric tons per year of CO2 out of the atmosphere.

The compact design, a shopping district and a trolley line from one end of the property to the other, reduced the need for auto travel. The estimated savings from the 2006 plan to the 2009 plan: 40,700 metric tons of CO2 per year and a fuel savings of $13 million.

“The savings analysis is highly conservative. Some of the homes might not be two-car homes, for instance,” Jones says. “The developer was pleasantly surprised to say the least.”

Although construction is on hold, Jones estimates the new design could save the developer $200 million overall and leave an extra $400 a month in homeowners’ pockets due to savings on transportation and other costs of living. That matters, Jones says, because savings for homeowners translates into stability for a community.

“Are these people more or less likely to be able to pay their mortgages, more or less likely to have foreclosed homes?” Jones asks.

Jones’ history with green building started closer to home. In 2003, he had a guiding hand in the development of Madera, a green community of 88 homes in Gainesville, where he built energy-efficient homes way above code as a test case. The Program for Resource Efficient Communities owned four of the homes and paid for Madera’s engineering. The community is water-efficient and well above Energy Star standards. Even though construction began during the economic downturn, Jones’ program made its money back and supported the case for resource efficiency.

“That’s how we learned something about development,” Jones says.

Water efficiency is one of the foundations for sustainable communities, particularly when it comes to landscaping. Jones says people sometimes view desalination as a solution to water scarcity since the ocean is the source. But desalination, he says, has a giant carbon footprint; it is 20 times more expensive than groundwater because of the energy required to process salt water.

“Water quality problems are growing all over the state. Regulation is coming, landscape ordinances are coming, water restrictions are coming,” Jones says. “The most risk-averse thing a developer can do is build green.”

Depending on how it is maintained, a lawn’s carbon footprint can be large or small. Under typical turf grass maintenance, the Program for Resource Efficient Communities has estimated the cost per year per 1,000 square feet of lawn: mowing emits 15 pounds of CO2; pesticides emit 1 pound of CO2; fertilizer emits 29 pounds of CO2. Pumping groundwater for a lawn adds 34 pounds of CO2 emissions, but using desalinated water for irrigation adds 579 pounds of CO2 emissions.

Communities built to reduce CO2 emissions associated with the way we live can help the people who move there by reducing commute times and providing green spaces.

“It’s not people who are demanding sprawling subdivisions, it’s the financial model of developers driving the shape and feel and look of developments. But developers are finally figuring it out,” Jones says. “In a climate change environment, developers will have to be smart and make different choices.”

Source:

- Pierce Jones, Director of the Program for Resource Efficient Communities

Related Website:

This article was originally featured in the Summer 2016 issue of Explore Magazine.