Pick up The Wall Street Journal or The New York Times or turn on CNBC’s Squawk Box or Bloomberg TV on any given day and if there’s a story about companies like Uber or Lyft or Pinterest or Airbnb going public, UF finance professor Jay Ritter is likely to be quoted.

The database of information about initial public offerings, or IPOs, that Ritter started building in 1979 for his doctoral dissertation has grown into an essential resource for journalists, investors, scholars and policy makers. Ritter has tracked so many variables about so many companies — more than 8,500 at last count — that he and his collaborators and students can answer just about any question that arises. Want to know the average first-day returns on IPOs? He’s got it. The fraction of companies with negative earnings? Got it. The number of U.S. IPOs from Chinese companies? Yep.

And because he is able to provide up-to-the-minute data and easily digestible quotes, he is now known throughout the industry as “Mr. IPO.” He has been quoted in The Wall Street Journal more than 180 times since 1989; nearly 100 times in USA Today; more than 50 times in Bloomberg Business Week and Bloomberg TV; and more than 40 times in The New York Times.

“Professor Ritter’s research into, and data about, IPOs is without peer,” says Mark Hulbert, a columnist at Dow Jones for MarketWatch, Barron’s and The Wall Street Journal. “He also is unfailingly willing to respond to reporters’ questions and help them understand the nuances of the historical record. I am in his debt for countless stories written over the last several decades that were infinitely better because of his insights.”

“If I wasn’t getting calls from journalists I probably wouldn’t bother updating things on a weekly basis, but with a sufficient demand it makes it worth my while,” says Ritter, the Joseph B. Cordell Eminent Scholar in UF’s Warrington College of Business. “One of the main things that I do for journalists is provide historical perspective and evidence. Responsible journalists like the kinds of facts I can provide.”

“Professor Ritter has for years provided his invaluable insight on the IPO market that helps members of the media find trends, explain the process and provide historical perspective amid the deal activity,” says Leslie Picker, a reporter for CNBC who has covered IPOs for six years. “We’ve consistently used his data and comments on air and online to improve our coverage of the IPO market.”

Ritter says he kind of stumbled into IPOs while searching for a dissertation topic.

“I had the good fortune to study under eight Nobel Prize winners at the University of Chicago,” says Ritter. “But if I had been more knowledgeable about the real world when I was working on my dissertation or if my professors were paying more attention, I would have realized that the IPO market had been dead for six years. They would have told me not to do it, that nobody cares about it, and they would have been right. But I didn’t know that, so I started working on IPOs at what turned out to be the start of a booming market.”

A market that since 1979 has included such high-profile names as Apple (1980), Microsoft (1986), Amazon (1997), Google (2004) and Facebook (2012).

“These are now among the largest market cap companies in the world, and all of them are pretty young companies, reflecting the dynamics of the US economy,” he notes.

What’s An IPO?

While many people have heard the term IPO, a lot of them probably don’t really understand what it means and even fewer have the resources or the access to invest in them, and Ritter says that’s OK.

For the record, NASDAQ defines an IPO as “a company’s first sale of stock to the public. Securities offered in an IPO are often, but not always, those of young, small companies seeking outside equity capital and a public market for their stock.”

“There’s no reason for everybody to be an expert, or even have minimal knowledge about how IPOs work, just as I don’t need to know the intricacies of what’s involved with the 5G network,” Ritter says of the coming super-fast cellular network.

And, he adds, individual investors probably wouldn’t want to invest in IPOs anyway.

“Smaller investors often suffer from what’s called the winner’s curse. If there’s lots of demand, they’re unlikely to get shares. If nobody else wants to buy, they’re likely to get shares, but those shares probably aren’t going to do very well. My view is that for most people investing in the stock market, buying and holding a low-fee index fund is the best strategy.”

Ritter says journalists often ask him if he thinks it’s fair that small investors can’t really get into the IPO market.

“It would concern me if the limited partners who invest in venture capital funds were getting unusually high returns,” he responds, “but generally they’re not doing that much better than the average investor.”

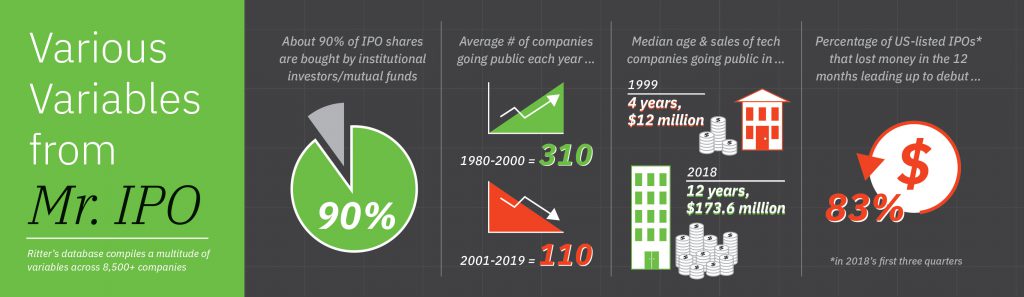

Ritter says that typically about 90 percent of IPO shares are bought by institutional investors such as mutual funds, but he adds that individuals will benefit indirectly if their 401(k) invests in successful IPOs.

IPOs are important to the economy, however, Ritter adds.

“IPOs are part of a well-functioning capital market, just as the banking system is part of a well-functioning capital market,” he says. “Raising equity capital from a public market of investors facilitates companies’ ability to grow.”

And, they enable the founders of the companies to cash in on their success.

“IPOs provide an opportunity for employees to sell some of their stock options, so that rather than just having big paper wealth they are actually able to buy a house and raise children,” he says.

In fact, Ritter says IPOs have actually helped to change the profile of America’s wealthiest people.

“According to Forbes, in the last 35 years the fraction of rich people who got their wealth through inheritance has plummeted,” he says.

Although they have only recently appeared in the public conscience, Ritter says IPOs have a long history in the financial world, dating back to 1602 when the Dutch East India Company first offered shares to raise capital for its explorations.

“Thomas Edison was funded primarily by venture capitalists,” Ritter cites as another example. “He was very oriented toward having his army of engineers and inventors and tinkerers work on things that he thought might be commercially viable, which would make him and his investors wealthier.”

Fewer, Bigger Companies

After the Internet bubble burst in 2000, the number of IPOs in the United States dropped dramatically and has stayed low. According to Ritter, between 1980 and 2000, an average of 310 companies went public each year. Since then, that number has dropped to 110 companies. The difference, he says, between IPOs in the early 2000s during the “dot.com” boom and bust and today is that Uber, Lyft, Pinterest and others are much bigger and more mature companies than was true of IPOs 20 years ago.

“Rather than just being a startup with an idea, these companies have a business model where they’ve demonstrated that people are willing to buy their goods and services,” he says.

Ritter’s data shows that the median age for tech companies going public in 1999 was four years, compared with 12 years in 2018. Median sales, meanwhile, were about $12 million in 1999, compared with $173.6 million in 2018.

“The reason that companies are waiting longer and growing bigger is that technology and globalization have in many industries made being big more important than it used to be, and getting big fast more important than it used to be,” he says.

Another reason there are fewer IPOs is that many successful startups never do go public, Ritter says. Instead they get acquired by a bigger tech company. According to Andy Serwer, editor and chief at Yahoo! Finance who frequently quotes Ritter, “since 2012 Facebook has bought 77 companies. Since 1998 Amazon has bought 83 companies. Since 1998 Apple has bought 108 — more than half over the past five years. And the granddaddy of them all, Google, has purchased 234 companies since 2001.”

Although they may be older and bigger than in the past, most newly public companies still aren’t profitable, Ritter says.

“About 83 percent of US-listed initial public offerings in 2018’s first three quarters involve companies that lost money in the 12 months leading up to their debut,” Ritter told The Wall Street Journal in October 2018.

While much of the focus is on well-known service providers like Uber and Airbnb, Ritter says biotech companies account for a large fraction of IPOs, even though many of them might not have an actual product, like a new drug, for years.

“Most of them don’t even have any revenue and they don’t expect to be selling products for many years,” he says, “but the market fully understands that and realizes that it’s difficult to come up with a successful drug and that most of the companies are going to end in failure. But, at the right price it can be a good investment. Your most likely outcome is that you’re going to earn a low return, even a negative return, but there’s a lot of upside potential. Every once in a while somebody comes up with a blockbuster, and they’re counting on that possibility.”

“One of the main things that I do for journalists is provide historical perspective and evidence. Responsible journalists like the kinds of facts I can provide.”

Jay Ritter

Ritter argues that sales are a much better predictor of IPO success than profitability.

“Historically, companies that have gone public with less than $50 million in sales have been disappointments,” he says. “Companies that have demonstrated that they have a product or service that people are willing to buy, on average, have been decent investments, not necessarily beating the market, but not underperforming either.”

Much of the IPO attention in 2019 was focused on the two ride-sharing giants — Uber and Lyft — and most of the news was bad. Uber lost nearly 8 percent of its initial $45 per share price on its first day, which Ritter says was the worst opening-day performance in terms of money lost that he has ever tracked, costing investors $617 million. On Nov. 1, it was trading at $31. Lyft opened at $72 per share and immediately started going down, by Nov. 1 it was at $43.

But Ritter has been predicting for months that those losses won’t mean much if Uber and Lyft eventually merge, which he has called “inevitable.”

Speaking on Yahoo! Finance in April, Ritter noted that Uber has a history of “calling a truce and merging” with rivals in other parts of the world, so he predicts that eventually the two competitors will become one.

Ritter says IPOs have provided a rich research environment for him and his students and he looks forward to continuing his tracking of companies that could lead the economy well into the 21st century.

“When I started working on IPOs 40 years ago, I had no way of knowing that the IPO market would boom,” he says. “Being in the right place at the right time has worked out well for me – and for the last 23 years, Gainesville has been the right place.”

Source:

Jay R. Ritter, Cordell Eminent Scholar, Department of Finance, Insurance and Real Estate

Related website:

This article was originally featured in the Fall 2019 issue of Explore Magazine.