Spring football may be on hiatus at Ben Hill Griffin Stadium, but on the rest of the University of Florida campus, the Gators are out in force.

Alligator mating season has arrived along with warmer weather, like always, but this year, the alligators pretty much have all 2,000 acres of campus to themselves. As these Gators go courting, they are likely to be more visible, says UF urban ecologist Mark Hostetler.

“The males have wanderlust,” says Hostetler, a professor in the Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation in UF’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. “They will be roaming around looking for mates.”

Any body of water on campus is fair game, so it would not be unusual for an alligator who finds too much competition in the mating game in Lake Alice to amble over to the Union Pond.

“It’s amazing to think of how an alligator, which is really low to the ground, can detect another lake a mile away, but they have a way of doing it,” says Hostetler. “They can go for miles.”

Alligators aren’t the only creatures enjoying a quieter campus. With less human traffic, shy species – lizards, turtles and tortoises, birds and even the occasional red fox – have more time for basking in the sun and traversing from one green space to the next. Hawks are likely finding it easier to hunt for food.

Spring is also peak migration season, with hundreds of bird species traveling through Florida. With fewer people out at night, the campus habitat may be more attractive as a pit stop, Hostetler says.

“Even a one-acre patch of woods or tree canopy helps,” Hostetler says. “These birds need places to refuel as they go from South America, Central America and the Caribbean to their northern breeding grounds.”

Less Light, Lower Volumes

Migrating species – great crested flycatchers, indigo buntings, Baltimore orioles, black and white warblers – usually like to forage away from human activity and rest at night away from the light. Although security lights are still on, many offices, labs and residence halls are emitting less light, and the reduction in light pollution is welcome for nocturnal migrating species and resident owls.

Noise pollution, too, is reduced.

It’s amazing to think of how an alligator, which is really low to the ground, can detect another lake a mile away, but they have a way of doing it. They can go for miles.”

Mark Hostetler

“With less noise, singing birds and croaking frogs can communicate better. Acoustically, they may do better in and around UF right now,” Hostetler says. “They can hear each other and find mates and set up territories.”

Hostetler says bird strikes – when birds crash into windows that reflect a clear sky or nearby vegetation – can be a problem for migrating species this time of year. A recent experiment in Newins-Ziegler Hall resulted in a simple solution. Strips of nylon cord spaced four inches apart were installed on reflective windows. Birds are not comfortable flying into an opening of four inches or less, so the installations, called Acopian Bird Savers, reduced window strikes, a significant cause of bird mortality, killing millions of birds a year, Hostetler says.

Hostetler encourages pedestrians on campus to enjoy wildlife from afar. He recalls a story about researchers who found themselves under attack when they were monitoring a campus mockingbird nest. Mockingbirds can recognize faces, and after repeated visits from the researchers, went on the attack.

“When they would repeatedly approach the nest, the parents would dive bomb them,” Hostetler says. “They wouldn’t react as much to new volunteers approaching the nest, but as soon as the original volunteers approached to check on the nest, they would attack.”

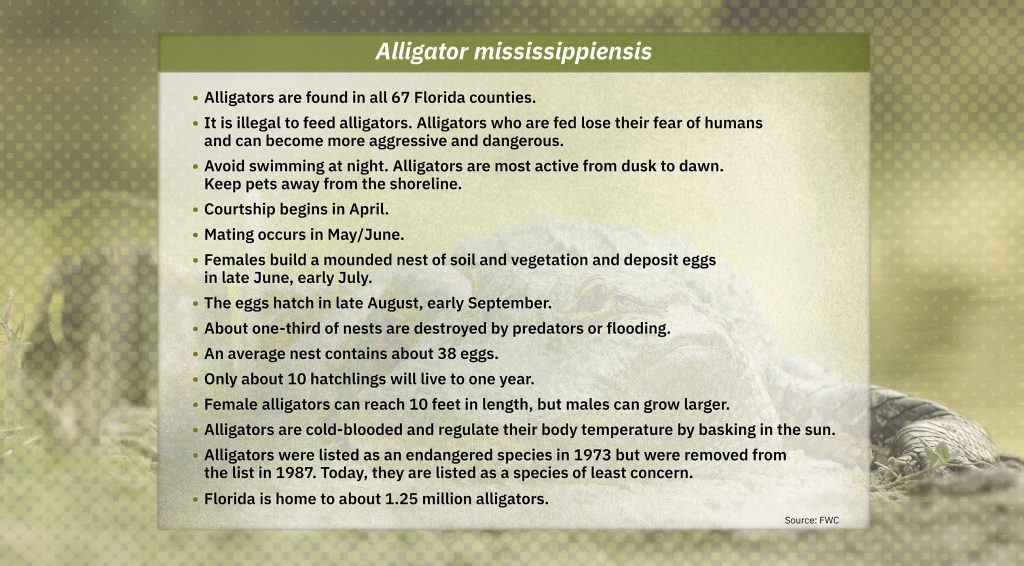

On the heels of alligator mating season, alligators will begin nesting, too. The females will make their nests of twigs and mud, generally near a shore, sometime in June and July and guard the eggs from predators, like curious humans. That makes safety the priority for alligator viewing, Hostetler says.

“Rule No. 1: Don’t try to get close to an alligator. Rule No. 2: Never feed an alligator.”

Although most campus creatures are enjoying the peace and quiet, some likely will welcome the end of social distancing and the return of humans.

“The squirrels and raccoons are probably getting thinner,” Hostetler says. “They’re missing out on the daily buffet of food scraps from the students.”

Source:

Mark Hostetler, UF Urban Ecologist and Professor

Related website:

For wildlife lovers, Hostetler recommends the City Nature Challenge April 24-27. To participate, visit Alachua County iNaturalist.