Caleb Stair was visiting his family’s farm in Pennsylvania one weekend when something happened that would change the direction of his academic career.

His brothers were driving home when they hit a deer with their car. His brothers were fine (the deer, alas, was not), but the accident prompted a lively family dinner table conversation.

UF Food and Resource Economics Department

“We were all wondering why that deer was over there,” says Stair, a new faculty member in the University of Florida’s Food and Resource Economics Department.

His grandfather suggested it was because hunters had scared the deer onto the road, and Stair, who was knee-deep in econometrics research at the time, had an idea. As part of his natural resource economics studies he had worked on climate issues and agricultural subsidies, so why not apply the same data analysis approaches to wildlife.

“I knew the data existed for me to do this sort of thing,” Stair said, “but I had never heard of it being done before.”

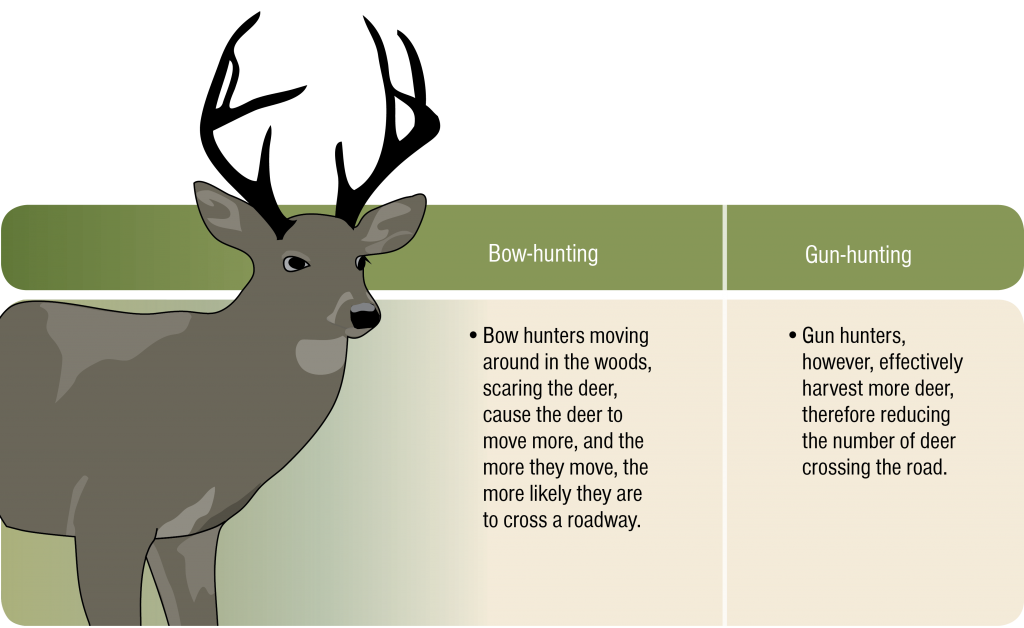

Stair designed a study to determine the effects of different hunting methods on deer-vehicle collisions. He decided to compare the effects of hunting with guns vs. hunting with bows to see which method was more effective at reducing deer-related vehicle accidents. His hypothesis was that bows, which are quiet, would not scare the deer, and that guns, which are loud, would.

Wrong.

“The average bow hunter is not Robin Hood,” Stair says. “Bow hunters moving around in the woods, scaring the deer, cause the deer to move more, and the more they move, the more likely they are to cross a roadway.”

Gun hunters, however, effectively harvest more deer, therefore reducing the number of deer crossing the road.

His mentor was enthusiastic about the study and asked him if he had any other ideas involving animals.

And a wildlife economist was born.

Data, Policy and Animals

In 2015, when Stair attended the Southern Regional Science Association Conference, he presented his research on the deer-related auto accidents and found he was the only economist discussing wildlife. Each year since, however, there have been more and more researchers presenting work related to wildlife and economics, an encouraging sign, Stair says, for the young field.

“I don’t want to be the only wildlife economist,” Stair says. “I’d like to drum up interest in prospective students and colleagues from other disciplines.”

Stair says he hopes wildlife economics can better inform policy makers about their decisions. For example, if a forest manager wants to increase the number of bow hunters in an area, what are the ramifications of that decision? Wildlife economists can provide statistics, costs, benefits and merge that knowledge with the knowledge of wildlife biologists who have a better understanding of animal behavior.

I don’t want to be the only wildlife economist. I’d like to drum up interest in prospective students and colleagues from other disciplines.”

Caleb Stair

Stair came to UF in 2019 as part of a hiring spree that brought to campus more than 600 new faculty, many of them early career academics like him. Students in his lectures, he says, are intrigued by applying economic principles to wildlife management and some have offered to help with research.

And now that he is in Florida, he welcomes the help. While he is accustomed to interactions with wildlife from his childhood on the Pennsylvania farm, wildlife in Florida takes some getting used to. One of his first stops was the St. Augustine Alligator Farm since he had never seen an alligator before. And not long after moving in to his McCarty Hall office, he saw an alligator in the pond next to the building.

“I was definitely the only person on the sidewalk who walked past and stopped,” Stair says. “To the students, it was just an alligator, whatever.”

To Stair, it was another research idea.

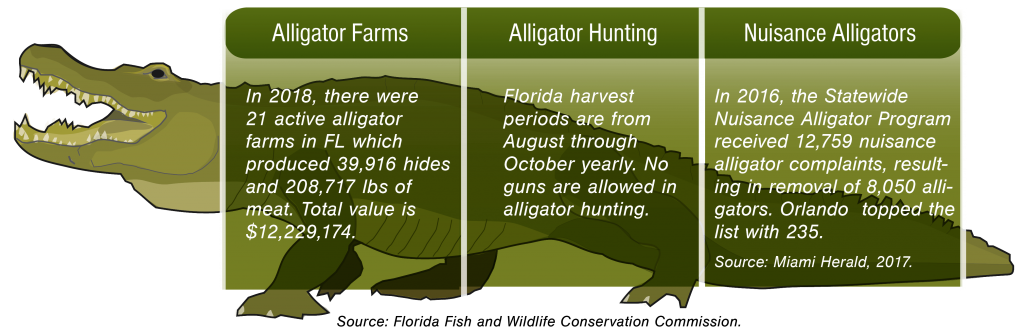

“What are the overall economic contributions of the American alligator to the state of Florida?” Stair asks. “How much money do alligators actually bring in to the state?”

A lot of factors go into that analysis: alligator farms, alligator hunting, alligator tourism, alligators on campus.

“I mean, the mascot for this university is an alligator,” Stair says.

How do you attach a value to a mascot?

“Good question. We’re still trying to figure that one out.”

“Jaws” Effect

Since “Jaws” is his favorite movie, it’s no surprise that Stair turned to sharks with an eye toward economic analysis.

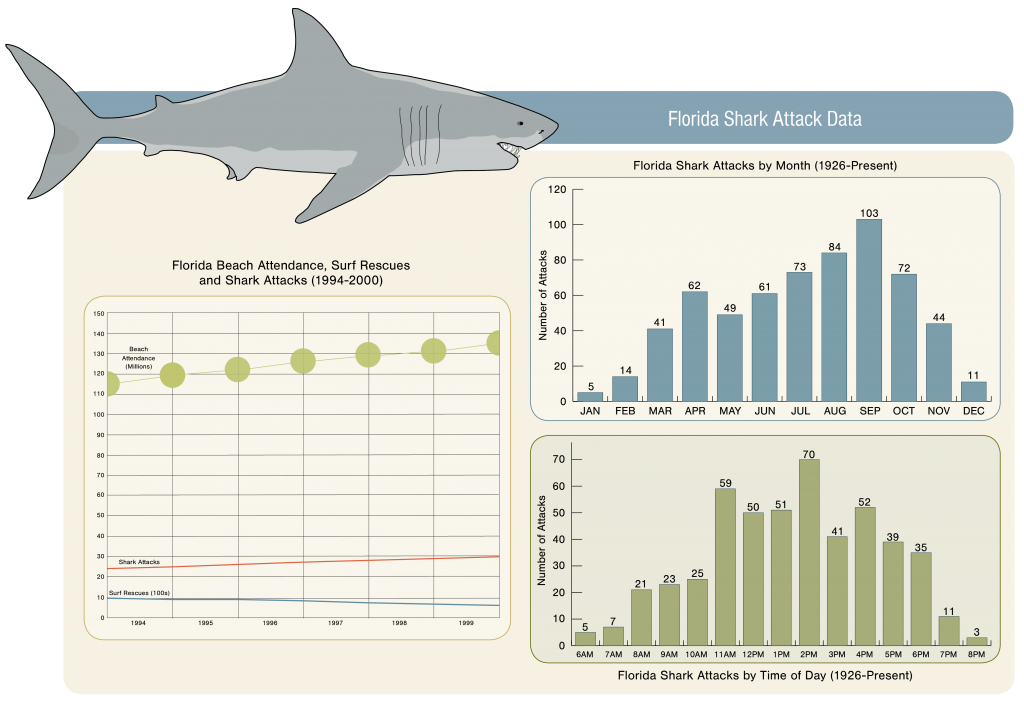

“There’s a scene in ‘Jaws’ where the mayor says, ‘We can’t tell everybody about the shark attacks because it would drive away all our business,’” Stair says. “That’s a perfect test for me, to see if shark attacks actually do drive away business.”

Using daily hotel occupancy data, Stair aimed to find out how the public responded to shark attacks following a string of eight in a short time around the Outer Banks. He found that immediately after the shark attacks there was no noticeable change. There was, however, a delayed impact from a month to a year later. He said it is possible that people already at the beach are not in a position to change their plans. People with time to regroup, however, likely do react to shark attacks by changing their plans.

joined a field school in Miami and spent eight days

helping the team tag sharks.

That work sparked a curiosity about sharks and further research. Stair, who had never been out on the ocean before, signed up for an eight-day field school experience tagging sharks off the coast of Miami “just like they do on Shark Week.”

“As academics, especially on the economics side of things, we need to get out of our offices more,” Stair says. “It brings us closer to our research — the sharks — but also to the people who are collecting the primary data.”

Stair also has tapped in to the treasure trove of data in UF’s International Shark Attack File, housed in the Florida Museum of Natural History. Next up, he plans to examine the effect of shark attacks on Airbnb stays in Florida. Some variables he wants to consider include the effect on Floridians vs. non-Floridians.

“A shark attack might not change your perspective if you’ve grown up in Florida or lived here a long time,” Stair says. “But it might if you’re visiting from Iowa.”

Another comparison is between the impacts of shark attacks versus the impacts of red tide, or hurricanes.

Stair also used his deer study with bears, substituting black bears in West Virginia for the deer. In West Virginia, property damage from black bears is common, so Stair examined whether hunting method — bow or gun — correlated with property damage claims. He found that an increase in archery hunters was associated with an increase in bear damage claims, whereas an increase in gun hunters was associated with a decrease in claims. The effect was even more pronounced with bears than with deer.

“A bear is essentially nature’s biological tank, with these massive shoulder blades,” Stair says. “You have to hit a very, very particular spot to eliminate a bear quickly with a bow.”

Bears and other migratory animals, such as the Florida panther, are a challenge for econometric research, Stair says. While there is plenty of economic data to mine, most of that data is confined to defined areas, like counties. A bear or panther, however, is oblivious to whether it has moved from one county into a neighboring county. Economists rely on data, bear damage claims for instance, to measure the effects of movements of mobile species, rather than radio tags, collars or GPS.

Receptive Audience

Stair says one of his first stops after moving into his office was the Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, and he was struck by how receptive they were to talking about his work.

“Everyone is totally willing to sit down with me and have a conversation. The collegiality at the University of Florida … I don’t have to really search to find somebody who thinks my research is worth their time.”

Within his department, too, he feels welcome. Professors looking to engage students in natural resource economics will mention his work with sharks when they try to demonstrate that economics is an interesting field.

“Maybe it’s the effect of Animal Planet or National Geographic or

Shark Week,” Stair says. “I guess I’m a fun one.”

As the nation’s third most populous state, but also a state with national forests and parks like the Everglades, humans and wildlife cross paths in Florida, creating a disconnect between biological carrying capacity and cultural carrying capacity in an area.

In Florida, I am in the hotbed state for wildlife economics.”

Caleb Stair

It’s a topic Stair says is particularly relevant in human-wildlife clashes, such as panthers killing cattle or alligators attacking people. Biological carrying capacity is the ability of an area to support a species with enough food, water and space to roam for the species to thrive. Cultural carrying capacity is how many of that animal — alligators or panthers, for instance — humans are willing to tolerate in an area. Comparing the two would require devising an effective means of measuring them, and then taking those measurements both before and after a negative interaction, like an alligator attack.

“Does an attack decrease tolerance and how long does that decrease in tolerance last over time? How long until we’re back to ‘OK, there are alligators in the pond?’” Stair asks.

It’s on the list of future projects.

“In Florida, I am in the hotbed state for wildlife economics,” Stair says.

“If I’m doing shark attack-related research, the University of Florida runs the International Shark Attack File, so I have ready access to the data. Florida has the largest reptile in the United States and a large population of those animals now. Burmese pythons in the Everglades. And the manatee population.”

Stair says the wealth of potential topics available in Florida could keep him busy for years to come.

“I could retire at the University of Florida,” Stair says, “and there would still be dozens of topics that I hadn’t even touched.”

Source:

- Caleb Stair, Lecturer, Economic Impact Analysis Program