A hiss emerges from a plastic bin, rising over the noise from a nearby highway.

On a levee at the edge of the Everglades, University of Florida wildlife ecologist Melissa Miller approaches the Rubbermaid container. Inside, double-bagged, lies 12 feet of coiled muscle with six rows of needle-sharp teeth and a powerful urge to escape.

It’s about to get its wish.

Miller feels for the snake’s head and grips just behind it, then lifts the 40-pound bundle, peeling back the thin cloth bags.

“It’s like unwrapping a horrible present,” she says.

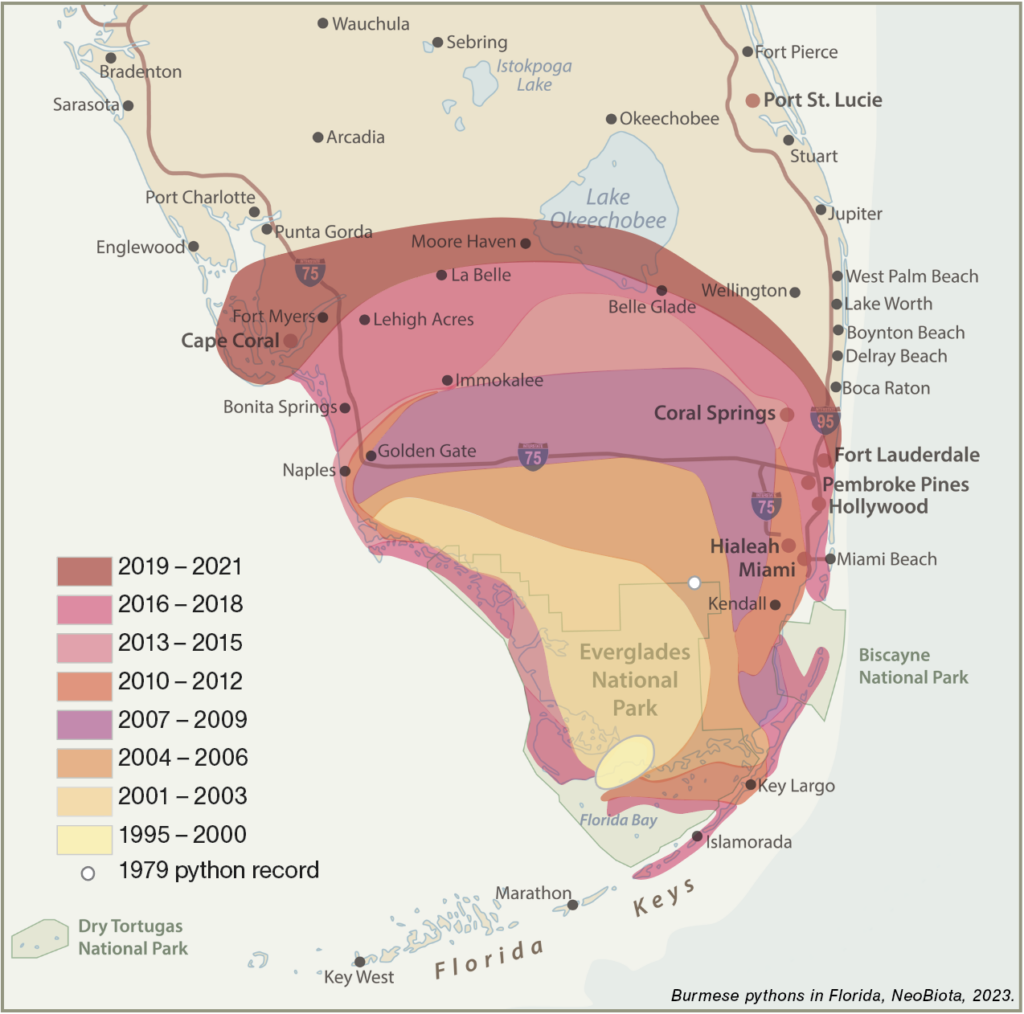

Burmese pythons have proliferated here, bringing parasites and pathogens and stressing an ecosystem we’ve invested billions to restore — not only for wildlife, but the storm protection and fresh water it provides South Florida residents. The snakes have spread north to Lake Okeechobee, south to Key Largo, east to Miami and west to Naples. One model suggests a third of the southern United States could sustain them.

Miller hopes this python and others in a new “scout snake” program can turn the tide. When it disappears into the marsh where it was captured two weeks ago, it will carry implants to track its movements. When groups of potential mates gather for breeding, the tagged snake will reveal their location, helping capture more of the invaders. But with these tech-equipped snakes, removal is only part of the goal.

Wading with pythons

“We’ve got a signal!” Miller says.

Miles out in the Everglades, UF wildlife biologist Brandon Welty holds an antenna aloft. A beep sounds from his handheld receiver, indicating the distance from another snake’s tracker. As they get nearer, the beeps get louder.

They’re searching for PyMo-1445, an earlier recruit to the scout program that’s been missing for almost a month. Two weeks ago, an aerial survey tracked the 9-foot male here, near a tree island rising up from the sawgrass. Tree islands seem to be a favorite hangout, but that’s one of many things we don’t know about pythons. If scientists hope to slow their spread, they need to understand their habitat preferences, along with their mating habits, how many of their young survive, how long they live in the wild, and much more.

“It’s the most studied invasive in South Florida, but there’s still so much we still don’t know,” says Miller, the principal investigator on the scout project. “If we can say, they’re breeding at this time of year, on this tree island, in this type of habitat, we have more ability to detect and remove pythons in the wild. This is an urgent need.”

Much of what we do know comes from the 18,000 pythons that have been euthanized. No one knows how many remain, but it’s likely many, many times that number.

Welty spent three years as a contractor, bagging hundreds of pythons on and around the levees built to control water flow. The levees turn into snake superhighways at night, making pythons easy to spot. We know less about those who reside in the inaccessible interior, which makes up 97% of the Everglades.

The airboat navigates ever-narrower trails through the swamp, until the GPS indicates they’re 300 yards from PyMo-1445’s last known location. The trails end, but the airboat keeps pushing through the razor-sharp sawgrass.

Beep.

“This one is elusive. He likes to move a lot,” says airboat operator Pete Donahue, cutting the engine.

Beep.

Alligator bellows reverberate like thunder. Welty watches the signal strength indicator on his receiver jump from three bars to five.

Beep.

Beep.

Beep.

“He’s here,” Welty says.

They slide off the boat and into the water. With the roar of the airboat engine extinguished, they hear only the trills of red-winged blackbirds flitting between the cattails. No breeze stirs the sawgrass. Silence.

“Keep your eyes peeled for movement,” Miller says.

Struggling through mats of submerged vegetation that drag at their pant legs, Miller and Welty inch closer, the mud beneath sucking at their boots. Donahue wades away from them in a flanking maneuver, sweeping out in a semicircle to keep the python between them. With no dry land nearby, snakes will bask where the thatch of cattails is thick enough to support their weight, or slip beneath the surface to swim when they want to travel quickly.

Being so close to a wild python doesn’t concern the team: their bites “bleed a lot, but don’t hurt that much,” Welty explains. They worry more about alligators, swarms of fire ants and water moccasins — not to mention heat stroke. Outside of the wet season that runs from May to October, they track exclusively on foot, since there’s not enough water for airboats. Wading through sawgrass “is more like climbing,” Miller says. “It’s exhausting.”

Beep.

Beep.

Beep.

Beep.

“He’s very close,” Welty says.

They squint into the shadows for the gleam of sunlight on scales, a glimpse of the intricate giraffe-like pattern that made Burmese pythons so prized as pets. Nothing.

“Is he moving?” Miller asks.

“He’s moving away from us,” Welty replies, “which means he’s in the water.”

They stop pursuing. If they chase PyMo-1445 too much, they’ll alter the behavior they’re trying to document. It’s disappointing: Welty estimates they were less than three feet away. But they’ll still be able to record habitat data as the snake slides unseen through the swamp.

“So many nice spots for snakes,” Miller sighs.

Not just a South Florida problem

Why are Burmese pythons here, 10,000 miles from their native range?

Floridians have reported occasional sightings since 1912, when the Tampa Daily Times wondered if “some ship brought these reptiles from the far east and the seamen, being tired of having them about, turned them loose on the coast.”

It’s hard to imagine intentionally sharing a seagoing vessel with a constrictor, but in the 1970s, it was trendy to share your home with one. In the later decades of a captive python’s 30-year lifespan, though — when rats no longer satisfy and feeding it requires rabbits and even pigs — a pet owner might look at a nearby swamp and think, why not? Hurricane damage to outdoor enclosures might also have contributed to accidental releases. Scientists presumed the 11 pythons spotted between 1995 and 2000 were isolated releases, but when smaller, younger pythons began popping up around the Everglades, even skeptics had to admit they were reproducing.

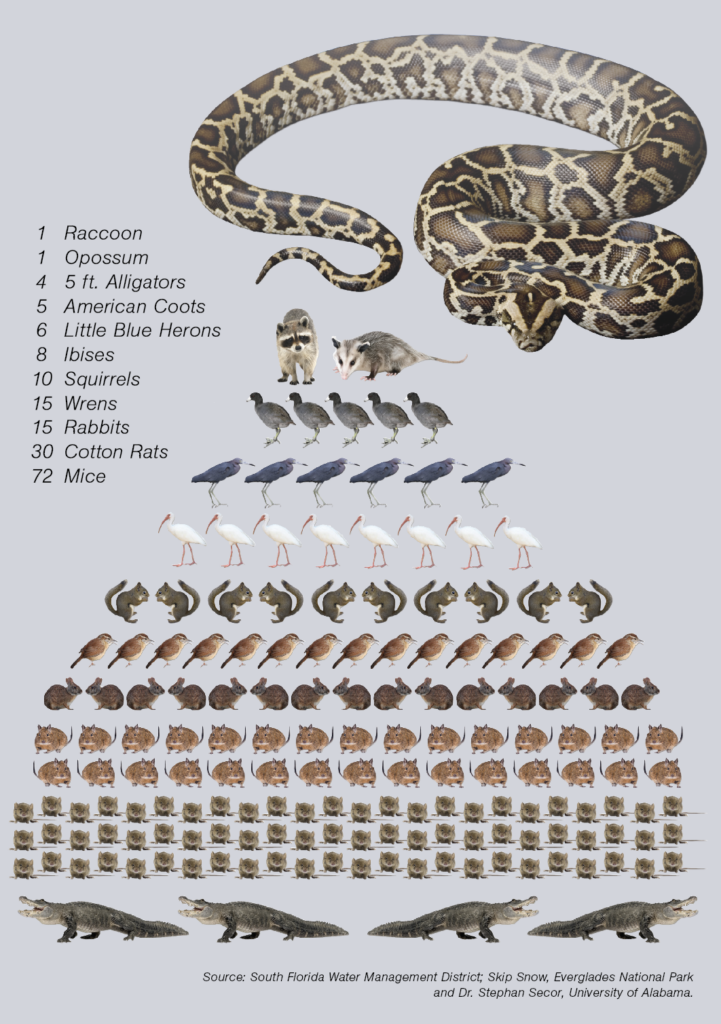

Three wild boars. Seventy-one alligators. Five bobcats and five domestic cats. A goat, an otter and five chickens — plus 94 round-tailed muskrats, 43 deer and 52 marsh rabbits. All of these were found in the digestive tracts of pythons in a 2023 study by UF wildlife ecologist Christina Romagosa. The 1,716 snakes sampled ate their way through 76 species, besting the fearsome beaks of great blue herons, munching the 8-foot wingspans of magnificent frigatebirds, and gobbling up threatened species like little blue herons and roseate spoonbills.

People aren’t in direct danger: The sole recorded human fatality from a wild python worldwide dates to 1900 (although they have caused traffic accidents when crossing the road). There’s never been an unprovoked attack on any of Everglades National Park’s million annual visitors. And unless you’ve lost a python in your bathroom, you’re incredibly unlikely to find one in your toilet, Miller assures, addressing a pervasive fear occasionally stoked by news coverage.

But for native wildlife and the ecosystems that sustain human life, pythons are bad news. They not only eat native creatures but compete for resources and disturb population dynamics in ways that could allow disease to spread — possibly to us. With much of the mammal population decimated by pythons, for example, mosquitoes have to feed on smaller creatures. In a 2017 study, IFAS scientists found mosquitoes were getting more blood meals from rodents that serve as reservoirs for Everglades virus, a subtype of equine encephalitis. That could translate to increased human exposure to the disease when those mosquitoes bite us. It doesn’t usually make people sick — but it’s mutating.

We once thought winters would limit pythons’ territory. A 2010 cold snap in South Florida slowed their spread, but Miller points out that if the snakes that survived were naturally more cold-hardy, the die-off effectively selected for offspring with that trait. A warming climate may also be in their corner, but there’s also a possibility they can learn to ride out lower temperatures by hiding in burrows or culverts. And pythons are very, very good at hiding.

“You can walk right past one and nine times out of 10 never even know it was there,” Welty says.

That’s where the scouts come in.

A snake in the grass

At the levee where the team is releasing the new scout snake, PyMo-1461, Welty points out a nearby burrow no bigger around than a basketball. The snake was captured there while guarding eggs — they’ve been known to lay more than 100 at a time.

She was thin from staying close to her nest — pythons don’t eat when guarding eggs — so Welty is glad to hear her hissing. It means she’s strong enough to be a good informant.

“She bit me through the bag already,” he warns.

Because PyMo-1461 was found within the study area and was big enough to handle the implants, the contractor who caught her submitted her to the scout program instead of euthanizing it. (One such candidate, a 16-footer, regurgitated a 6-foot alligator while in holding. Neither survived.) From there, PyMo-1461 went to a local veterinarian who implanted the radio tags — two, in case one malfunctions — that emit a frequency unique to that snake. Her new accessories also include an accelerometer, which can reveal more about her movements and behaviors, and a durable threadlike tag that tells contractors they’ve found a scout snake that shouldn’t be killed.

The five-year project, in collaboration with the United States Geological Survey, Fort Collins Science Center, South Florida Water Management District and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, is just beginning, with seven males and seven females roaming the Everglades.

“When people see the releases on social media, they ask, ‘Are they fixed?’” Miller says.

They’re not. Scout males help the team lure in and euthanize large females of reproductive age, and females help them understand reproductive behavior. Neither works if the snakes are sterilized. Miller understands why people might be confused about re-releasing a species we’re trying so hard to eliminate, but she knows it’s a necessary step. And it’s working: Welty has already intercepted two more pythons while tracking the scouts. The planned addition of drones to their arsenal will allow easier access to remote areas and let them track more snakes. (The team is also working on high-tech solutions for invasive species like tegus, training artificial intelligence-enabled traps to recognize and capture the voracious black-and-white lizards that can grow to four feet long.)

Miller places the python on the levee. Then she releases the head and quickly backs away. PyMo-1461 coils up as if to strike, reconsiders. After a few minutes, the snake lurches off of the gravel road toward its burrow. The second her tail disappears into the grass, she’s invisible, despite being inches away.

In four days, though — and throughout the five-year study — they’ll meet again.

Photos by Cat Wofford, UF/IFAS

Source:

Melissa Miller

Research Assistant Scientist

UF/IFAS Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center

melissamiller@ufl.edu

Hear the Story

The audio version of this story is available on our YouTube.