The World to Come: Art in the Age of Anthropocene explores an era of rapid, radical and irrevocable ecological change through works of art by 45 international contemporary artists. Organized by Harn Museum Curator of Contemporary Art Kerry Oliver-Smith, the exhibition examines the fate of the planet through more than 65 works of photography, film, sculpture and mixed media.

While geological epochs are known as products of slow change, the Anthropocene has been characterized by speed. Runaway climate change, rising water, surging population, nonstop extinction and expanding technologies compress our breathless sense of space and time. Human impact has created a profound and disastrous effect on the Earth. Artists in the exhibition respond by upending the status quo, challenging human mastery over nature and attuning us to the deep bond between human and nonhuman life.

The World to Come unfolds around seven overlapping themes: “Deluge,” “Raw Material,” “Consumption,” “Extinction,” “Symbiosis and Multispecies,” “Justice” and “Imaginary Futures.” Topics range from disaster, environmental devastation and loss to the emergence of new bonds and alliances between humans and nonhumans. Also considered is the magnitude of waste and growing populations, the laws of nature, inequality and protest. Lastly, artists explore the effects of technology and make a call for optimism with new ways of imagining a vibrant future for the world to come.

After debuting at the Harn Museum in September 2018, the exhibition opens at the University of Michigan Museum of Art in April.

“We Can Have Conservation And Development In The Amazon.”

Angélica Almeyda Zambrano, Assistant Professor of Tourism, Recreation & Sport Management, College of Health and Human Performance

As co-director of the GatorEye Unmanned Flying Laboratory, Almeyda Zambrano is helping sustainable tourism gain ground as an alternative to deforestation. She’s pioneering data-gathering via 3D drone scans in the Amazon and other key conservation areas. “Typically, I would ask people about their forest and rely on those answers. But if I can quickly fly over it, I can get gigabytes of data on the quality of that forest — for example, how much carbon is it sequestering, or the area of secondary vs. old-growth forest,” she says. “My next step is to compare how ecotourism can result in environmental and social win-wins.”

“Paradise on Fire” Series, by UF College of the Arts Professor Sergio Vega, 2007, courtesy of the artist

“What Can Oncology Learn From Ecology?”

Brent Reynolds, Professor of Neurosurgery, UF Health

Madan Oli, Professor of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, UF/IFAS

Can wisdom from wildlife help us outsmart cancer? That’s what the 10-year collaboration between Reynolds, a neuroscientist, and Oli, an ecologist, asks — and answers. Together, they launched a discipline called eco-oncology, applying what we know about animal populations to tumor cells, which communicate, migrate and reproduce much as wildlife does. One lesson: When managing a pest plaguing a crop, it’s rarely beneficial to try to defeat it completely. That approach can leave behind only the hardiest invaders, which come back even stronger. The same is true for tumors. Instead of pummeling them until only the strongest tumor cells remain, could we manage the population, keeping the toughest ones in check? Lessons like these could reshape our approach to cancer treatment.

“Caribou Migration” by Subhankar Banerjee, 2002, loan courtesy of Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire; purchased through the Charles F. Venrick 1936 Fund

“Your Home Is Your Castle, And Castles Aren’t Blown Down By Wind.”

David Prevatt, Associate Professor of Civil and Coastal Engineering, Herbert Wertheim College of Engineering

Knowing how to protect homes from wind damage doesn’t help if homeowners don’t act on it. Prevatt looks at ways to take engineering knowledge to the public to safeguard life and property. “We have to make a long-term commitment to sustainable construction,” he says. “The houses we build today will affect the vulnerability of our community for the next 50 to 70 years. As civil engineers, it is our responsibility to ensure you can find the construction technology so you won’t have to live with the uncertainty that the next hurricane is going to blow your house away.”

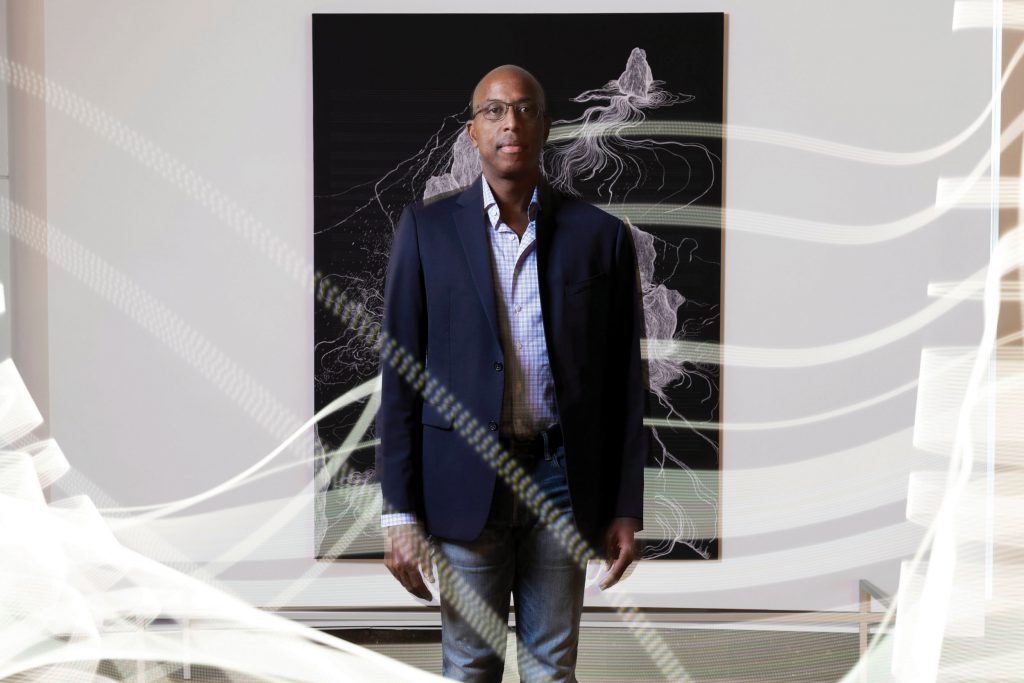

“Untitled,” 2015, by Sandra Cinto, 2015, courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

“Will Get This Right.”

Zoliswa “Zoe” Nhleko, Doctoral Candidate in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences

A junior scientist with South African National Parks, Nhleko studies how stress from poaching affects white rhinos. One question is how they choose their habitat. It’s not clear why they prefer the southern part of Kruger National Park: “It’s like there is a line they will not cross. Once we understand what they are looking for, then we may be able to move them from high-poaching areas into suitable habitats in safer areas,” she says. “We could manipulate the environment and make it unsuitable in a way that gets them out of danger, because by themselves, they’re not doing it. They’re not scared of people, but they should be.”

“White Rhino, Namibia,” by Maroesjka Lavigne from the series Land of Nothingness, 2015, courtesy of Robert Mann Gallery, New York

“We’re Not Just Here To Dabble Around. We’re Here To Answer Questions.”

Christine Angelini, Assistant Professor of Environmental Engineering Sciences, Herbert Wertheim College of Engineering

Angelini works to understand and restore resilient coastal ecosystems, which can protect us from storms and algae blooms and support fishing and tourism. “I’ve been working a lot more with managers here in Florida that are on the ground doing restoration activities. I almost think it’s the opposite of what’s happening in the political climate of divisions, of folks not talking to each other. There’s increased communication going on between scientists and managers where we’re able to do more science-based management and scientists are doing more research that’s relevant — immediately relevant — to management.”

“Swamp and Pipeline, Cancer Alley, Louisiana” by Richard Misrach, 1998, museum purchase, gift of Dr. and Mrs. David A. Cofrin

“My Dream Is For Food Security Worries To Becoming Something Of The Past.”

Pedro Sanchez, Professor of Soil and Water Sciences, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences

A World Food Prize Laureate, Sanchez led a team that tripled rice yields in Peru in the 1970s and has been instrumental in boosting corn yields in sub-Saharan Africa, which have nearly doubled since 2005. Farmers in more than 20 countries use the soil-improvement strategies he helped develop. “My hope is that in 20 years, we can say, ‘Remember when we were worried about food security in the world? Remember when nutrition was a concern? Remember when agriculture was damaging the environment?’ My dream would be that in most countries, this will be something of the past.”

“Oscar” from the series Terrain, by Jackie Nickerson, 2012, courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

“The Amazon Is Essential.”

Robert Walker, Professor of Geography and Latin American Studies, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and Center for Latin American Studies

Walker combines remote-sensing data and field interviews of farmers, loggers, ranchers and indigenous groups in the Amazon to reveal threats to the area and its people. “A disturbance on one part of the global surface can impact a place far, far away. Some computer models show that a desiccated Amazon could actually reduce rainfalls and affect agriculture in the Mississippi Valley,” he says. “The Amazon is the richest store of biodiversity on the planet. You need to have that in order to keep the planet capable of evolutionary adaptation…and anyone concerned about cultural variety and the integrity of native peoples has to place very high value on the Amazon.”

“Yanomami” by Claudia Andujar from O Invisivel series, 1976,

courtesy of Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

Photos by Brianne Lehan and Lyon Duong