Phoebe Stubblefield’s parents grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and even though she visited the city every summer as a child, she knew little about the race riot there in 1921 that wiped out the flourishing Black community of Greenwood and left as many as 300 people dead.

“There was no discussion about the race riot when I was a child. It wasn’t until the late 1990s that I heard any family history,” she recalls. “Then my mother says, ‘Oh, yeah, your Aunt Anna lost her house.’”

It was like secret knowledge. I get the impression that, often, Black people — especially when moving around — dealt with horrors by not talking about them.

— Phoebe Stubblefield

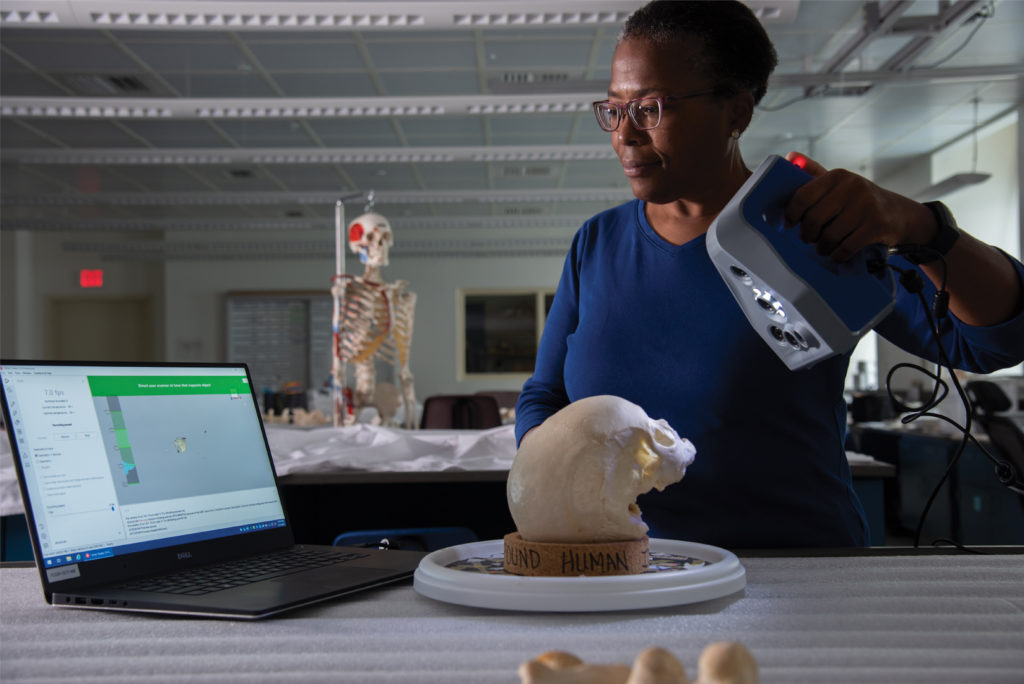

Stubblefield, a forensic anthropologist and interim director of UF’s renowned C. A. Pound Human Identification Laboratory, says her story is not unusual, which has made the search for the graves of Black people killed in what has become known as the Tulsa Race Massacre that much more challenging.

“It was like secret knowledge,” Stubblefield told PBS NewsHour in 2020. “I get the impression that, often, Black people — especially when moving around — dealt with horrors by not talking about them.”

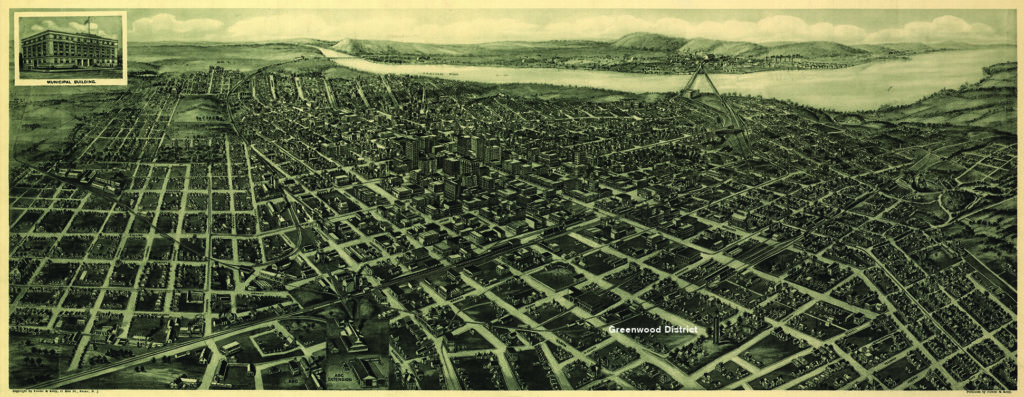

According to historical accounts, in 1921 the Greenwood District of Tulsa was a thriving African American community known nationally as “the Black Wall Street.” Although many of the residents worked in the white community, they returned to Greenwood to live and conduct their business. Churches, schools, banks, clothing and dry goods stores lined the main streets of Greenwood, while homes occupied the side streets.

But on May 30, a young Black man named Dick Rowland found himself alone in an elevator with a white woman in downtown Tulsa. Exactly what happened will never be known, but the next day police arrested Rowland and began an investigation.

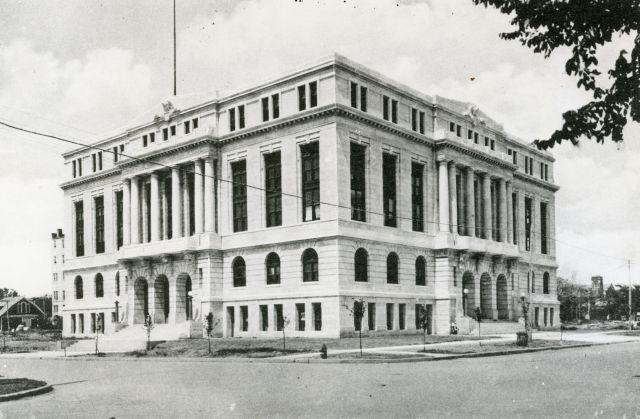

According to an account from the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum, “an inflammatory report in the May 31 edition of the Tulsa Tribune spurred a confrontation between Black and white armed mobs around the courthouse where the sheriff and his men had barricaded the top floor to protect Rowland. Shots were fired and the outnumbered African Americans began retreating to the Greenwood District.”

In 2001, the Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 reported that, “At the eruption of violence, civil officials selected many men, all of them white and some of them participants in that violence, and made those men their agents as deputies. In that capacity, deputies did not stem the violence but added to it, often through overt acts that were themselves illegal. Public officials provided firearms and ammunition to individuals, again all of them white. Units of the Oklahoma National Guard participated in the mass arrests of all, or nearly all, of Greenwood’s residents.

“They removed them to other parts of the city, and detained them in holding centers. Entering the Greenwood district, people stole, damaged, or destroyed personal property left behind in homes and businesses. People, some of them agents of government, also deliberately burned or otherwise destroyed homes credibly estimated to have numbered 1,256, along with virtually every other structure — including churches, schools, businesses, even a hospital and library — in the Greenwood district.

“Despite duties to preserve order and to protect property, no government at any level offered adequate resistance, if any at all, to what amounted to the destruction of the Greenwood neighborhood. Although the exact total can never be determined, credible evidence makes it probable that many people, likely numbering between 100-300, were killed during the massacre.”

About 24 hours after the violence erupted, it ceased, but 35 city blocks of Greenwood had been burned to the ground.

Suppressing History

Stubblefield says that despite the enormity of the event, in the weeks, years and decades that followed, the Black community sought to quickly rebuild and the white community sought to repress the story.

“Immediately after the massacre, Tulsa leaders tried to pass a fire code restriction to prevent rebuilding, but it was so restrictive that other city leaders said even the white people wouldn’t be able to build,” she says. “Leaders in Greenwood urged people to rebuild as fast as they could, to put anything on their property before city leaders could come up with another restrictive code.”

So life returned to a new normal, and as the years went by people forgot, and just to make sure they didn’t remember, by the 1960s Stubblefield says “the city and state of Oklahoma were actively suppressing awareness of the riot.”

Historians have spent years searching for a copy of the May 31, 1921 edition of the Tulsa Tribune, which is purported to have had an incendiary story about Rowland’s arrest on the front page. But original copies of the newspaper have never been found, and the story was redacted from a microfilm copy made in the 1950s.

It wasn’t until 1997, when the city established the race riot commission, that details of the event began to emerge. But while the commission answered many questions about the massacre and the events surrounding it, the question of how many members of the Greenwood community died and where they were buried continued to haunt the city.

As the 2021 centennial of the massacre approached, Tulsa Mayor G.T. Bynum initiated the 1921 Graves Investigation, saying: “The only way to move forward in our work to bring about reconciliation in Tulsa is by seeking the truth honestly. As we open this investigation 99 years later, there are both unknowns and truths to uncover. But we are committed to exploring what happened in 1921 through a collective and transparent process — filling gaps in our city’s history, and providing healing and justice to our community.”

As one of the nation’s leading forensic anthropologists, Stubblefield was a natural addition to the Graves Investigation. She leads skeletal recovery and analysis for the Physical Investigation Committee, which is chaired by historian Scott Ellsworth, who is also in charge of identifying viable sites. Oklahoma State Archaeologist Kary Stackelbeck is in charge of archaeology. The team, which includes several other UF alumni and graduate students, is excavating in cemeteries and other locations where eyewitness accounts, mortuary records and other reports indicate Black victims of the massacre may be buried.

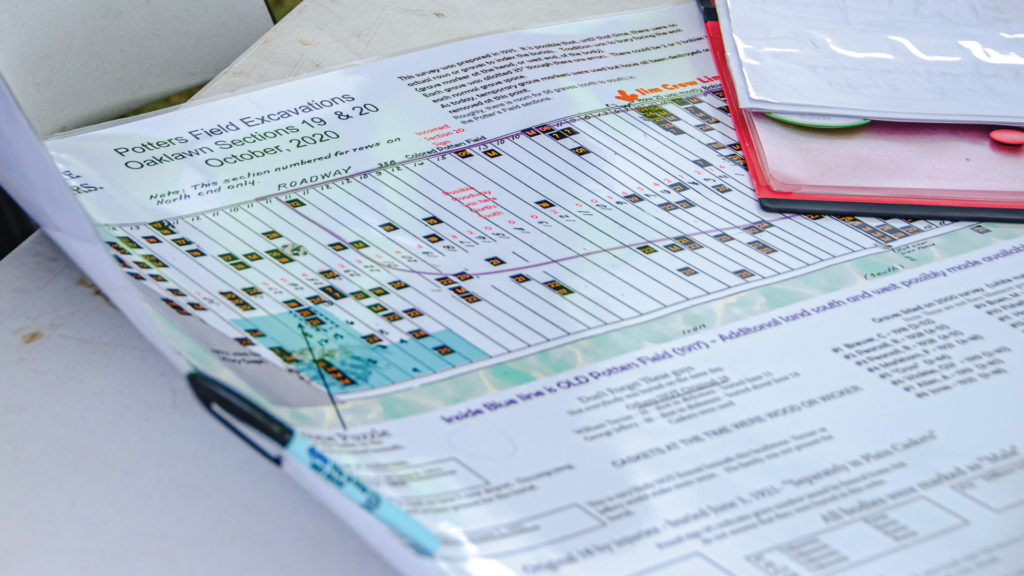

In 2019, Stackelbeck and a team of experts from the Oklahoma Archeological Survey, based at the University of Oklahoma, began using a variety of tools, including remote sensing, at three initial target sites from the race riot commission report — Oaklawn Cemetery, Newblock Park and Rolling Oaks Cemetery (formerly Booker T. Washington Cemetery).

Based on anomalies in ground-penetrating radar scans, in July 2020 the team began test excavations in a section of the city-owned Oaklawn Cemetery, but after eight days of digging, no remains were found.

In October, they moved to another area of the cemetery, a potter’s field where funeral home records and other documents from 1921 indicated at least 18 African American massacre victims were buried.

During that excavation, the team found evidence of at least 12 coffins holding human remains. Stubblefield says weather conditions were deteriorating in October, so the team secured the excavation site and returned the soil that had been removed. She says the team hopes to return in June to resume excavating.

While the team appears to be closing in on recorded burials, it is reports of mass burials of perhaps hundreds of people that continue to challenge the researchers.

Two areas near a railroad track — The Canes and Newblock Park — are of particular interest.

“There are eyewitness statements that members of the National Guard brought in a rail car covered with bodies and that they were moved downhill into a trench,” Stubblefield says. “Aerial photos show that there was a bluff that was there then, and it’s still there now, so that supports these accounts.”

She says The Canes is now a homeless camp with a lot of younger trees that would have grown up after the massacre. Newblock Park is near a sewer lift station, so there has been considerable disturbance to the ground over the years, but she remains hopeful.

William Maples’ Legacy

Although most of the Pound Laboratory’s work is in service to law enforcement investigating active cases, Stubblefield’s participation in the Tulsa Massacre project continues a long history of forensic anthropology at UF.

Stubblefield was completing her master’s degree at the University of Texas in 1993 when a friend attending the UF College of Law, remembering her interest in forensic anthropology, sent her a copy of “Dead Men Do Tell Tales,” an autobiography by renowned UF forensic anthropologist William Maples.

Maples had built an international reputation through his involvement in historical cases, such as the one to determine if President Zachary Taylor had been poisoned with arsenic and the investigation of remains found in Russia that Maples confirmed to be of Czar Nicholas II and his family.

But it was Maples’ many contemporary cases that intrigued Stubblefield.

“I could see that he had an active career. He had a well-developed lab. I knew based on his activity that he would have a wealth of experience,” she says. “I could see when I read Dr. Maples’ book that I had a strong chance to get knowledge directly. To understand what a gunshot wound looks like, or a stab wound looks like, in different qualities of bone or with weathering; to learn how force is transmitted through a whole skeleton; or how an intact skeleton can vary for one individual to another, you have to experience it.”

So she applied to UF and was admitted, as Maples last graduate student before he died in 1997. She completed her doctorate in 2003, then spent 15 years in the anthropology department at the University of North Dakota before returning to UF as a research assistant scientist in the Pound Lab that Maples established.

“As Dr. Maples’ last graduate student, I am proud to return to continue his traditions in forensic analysis, while expanding the lab’s interests in research,” she says. “I have a collegial and interdisciplinary focus that I foresee will bring new collaborations to the Pound Lab. I have a growing interest in interdisciplinary research within anthropology, especially in exploring the intersection of cultural anthropology with forensic science.”

And that is exactly what she is doing in Tulsa, where a history of segregation, of KKK rallies and lynchings provide context for the massacre, the rebuilding and the silence that endured for almost a century.

Stubblefield says that if remains are found, it will be up to an oversight committee made up mostly of residents from the Black community to decide what they want done with them. One decision will be about conducting DNA analysis.

“There’s a long history of using Black bodies for research, so I’m trying very hard to keep the analysis on site and do whatever I can to involve the people of Tulsa,” she says.

Stubblefield says there would be considerable genealogical research needed to identify potential relatives, and although she would like to try to conduct DNA analysis, “I want the Black people of Tulsa to decide.”

As Dr. Maples’ last graduate student, I am proud to return to continue his traditions in forensic analysis, while expanding the lab’s interests in research.

— Phoebe Stubblefield

Source:

Phoebe Stubblefield

Research Scientist and Interim Director

C.A. Pound Human Identification Laboratory

Hear the Story

The audio version of this story is available on our YouTube.

Related Website: