I

n the hunt for fresh clues about emerging illicit drug use and accidental poisonings from drugs, University of Florida epidemiologist Linda Cottler and her team cast a wide net.

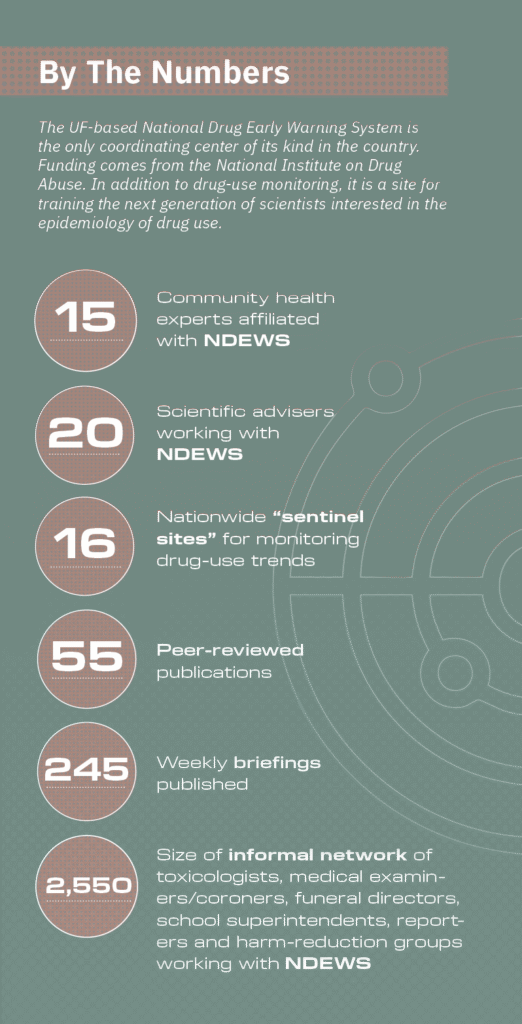

Cottler’s group, the UF-based National Drug Early Warning System (NDEWS), combs through emergency medical service data. They use rapid, weekend-long surveys and scour the social media site Reddit to get timely insights about new drug-use trends. And they collect troves of information from an array of sources, including federal drug seizures, toxicologists, funeral directors, school superintendents and even curious journalists.

The goal is simple: Collect and analyze divergent data about drug use, harmonize it with other figures and disseminate the information as quickly and widely as possible.

“We want to figure out where the next overdoses are going to occur,” Cottler says.

The NDEWS Coordinating Center occupies a unique position in the world of epidemiology. When UF took over NDEWS in mid-2020, Cottler envisioned a nimble group that could put out crucial information about drug-use trends in close to real time. She also aspired to substantially build its audience of health departments, emergency medical and other groups and agencies on the front lines of substance use. From a base of zero subscribers, NDEWS has grown its weekly briefing list to over 6,400.

We want to figure out where the next overdoses are going to occur.” —Linda Cottler

To do that, Cottler assembled a leadership team from three universities. The group includes a drug use epidemiologist; a forensic toxicologist; a Florida Atlantic University associate professor of psychology; and a distinguished psychiatry professor who specializes in substance abuse. Cottler is a professor in the College of Public Health and Health Professions and the College of Medicine.

NDEWS has deployed a host of innovative drug-surveillance methods in recent years. Its Rapid Street Reporting program sends college students into communities to gather real-time substance use data. The students conduct brief, anonymous interviews with local residents. Since 2021, they have done surveys in 21 cities. The survey covers about 100 drugs and documents their adverse effects on people. It also details the rise of new psychoactive substances.

As NDEWS’ other tools are deployed, a timely picture of current drug use comes into focus. Reddit “scraping” led by Elan Barenholtz, an NDEWS co-investigator and FAU faculty member, helps to detect early signs of new drug trends — although it can lack location specifics. Dispatch data from 911 centers are used to generate “heat maps” of overdose activity, including the time and day, helping to target interventions.

Reddit discussions offer snippets of information that have reliably correlated with drug use in communities. When paired with data about fatal drug overdoses and drug seizures, a detailed picture emerges quickly. In one instance, anecdotal reports about pentobarbital — a potent sedative — emerging in the illicit drug supply were rapidly investigated and turned into a published paper.

“We’re uniquely situated to identify emerging drugs. We want to impact the degree of drug use and mortality by disseminating reliable information,” says Bruce Goldberger, a UF forensic toxicologist and NDEWS co-investigator.

For the NDEWS team, agility matters. Drug use trends can change as quickly as an illicit chemist can alter a molecule. Drug laws, and even medical examiners’ testing, struggle to keep up.

“One molecule can change and it will not be illegal,” Cottler says.

While the chase can be exhausting, NDEWS continues to be successful in its pursuit of emerging drugs. Cottler’s team was among the first to notice an uptick in the use of “pink cocaine,” a misnamed drug cocktail that typically contains the anesthetic ketamine and other drugs. NDEWS is seeing psychedelic mushrooms consistently ranked as the third-most used illicit drug in the country.

Fentanyl, a potent pain reliever, is now being laced with an array of non-opioid sedatives and anesthetics, NDEWS has found. Depending on the substance, people who ingest illicit fentanyl have reported numbness, irregular heartbeat and other complications that can land them in the intensive care unit. One of the anesthetics, a veterinary sedative known as medetomidine, has led to an alarming increase in hospital admissions.

“We received a query regarding the appearance of local anesthetics in the illicit fentanyl drug supply. People are complaining that their arm goes numb when they inject fentanyl,” Goldberger says.

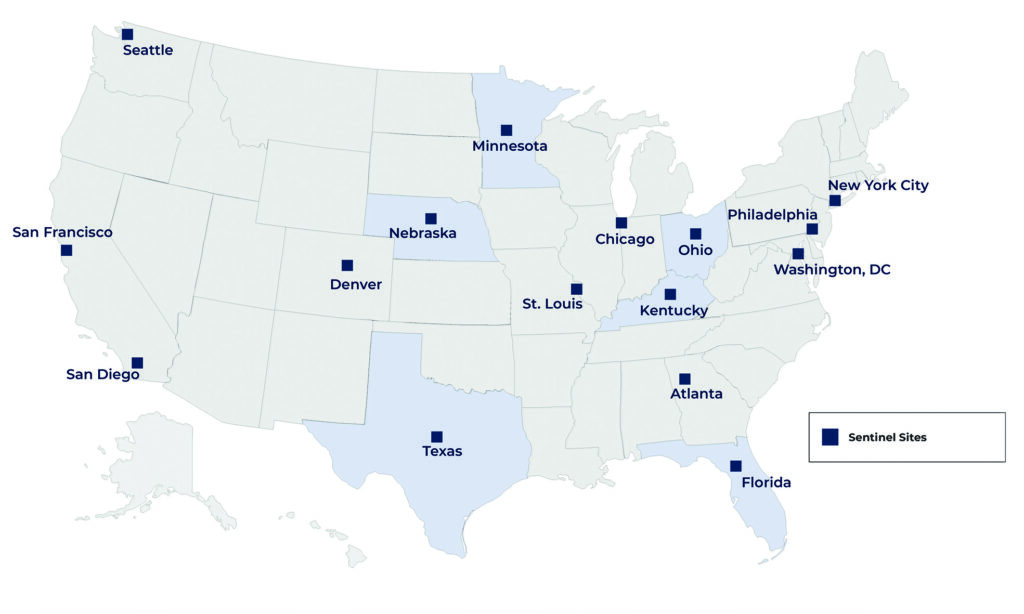

Sixteen sentinel sites around the country collect and submit data to NDEWS, giving the group consistent and timely access to local drug use trends. When 911 heat maps indicated a rise in overdoses had landed Chicago in the top 10 nationally, they asked NDEWS for a longer, more detailed report on drug activity in the area. Similar requests have come in from authorities in Washington state and New York City. That, Cottler says, helps local authorities deploy law enforcement, emergency services and overdose prevention resources.

Just this year, NDEWS’ hotspot alerts have identified an array of drug-use trends that otherwise might go undetected on a broader scale. From the Idaho Panhandle to Martin County in southeast Florida, overdoses involving the opioid-like substance kratom were uncovered. Overdoses involving tianeptine, an opioid-like substance nicknamed “gas station heroin,” were spotted in areas as diverse as rural northwestern Michigan and the Denver metro area — as well as 23 other counties nationwide.

As a testament to NDEWS’ value and relevance, Cottler notes the group’s weekly reports can change right away depending on what is happening.

“We think every week about what we’re going to publish. And then, all of a sudden, something turns up in South Dakota or Atlanta, and we change our report completely,” she says.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse recently reaffirmed UF’s role as the NDEWS coordinating center.

“This information can help communities know where to distribute resources like the opioid overdose treatment naloxone or target other services or prevention interventions. The recent renewal of a cooperative agreement demonstrates NIDA’s commitment to this program and the importance of continuing to identify new indicators of changing drug-use patterns and disseminate this information to communities who can use it to inform their public health response,” says Wilson Compton, NIDA’s deputy director.

For NDEWS Deputy Director Joseph J. Palamar, current data such as law enforcement drug seizures and poison center reports are paramount. Officially, he’s a professor of population health at New York University Langone Medical Center. Practically, he describes himself as a drug use epidemiologist.

Palamar brings a unique level of lived experience, something he says helps him thrive on the job. He once passed all the screenings to be a New York City police officer but was too young to join the force right away.

“But the next thing I knew, I was a fixture in the New York City after-hours club scene,” Palamar says. “I was surrounded by drugs — ecstasy, ketamine, GHB. Later, I was working on club drug research studies at NYU. It’s almost been a quarter-century and I’m still focusing largely on party drugs.”

Palamar, who has helped raise awareness about “pink cocaine,” says fentanyl and other novel opioids should be a major focus due to their high lethality and prevalence in unintentional exposures. One of NDEWS’ strengths is early detection and dissemination of drug trends, he notes. And while Reddit has its limitations for epidemiology, it’s a useful trend-spotting tool. The group has found that chatter about a drug often increases before poisonings occur. That, he says, can buy valuable time for interventions and awareness.

“It’s an early warning system. We focus on drug trends and novel drug trends in as close to real time as we possibly can,” he says.

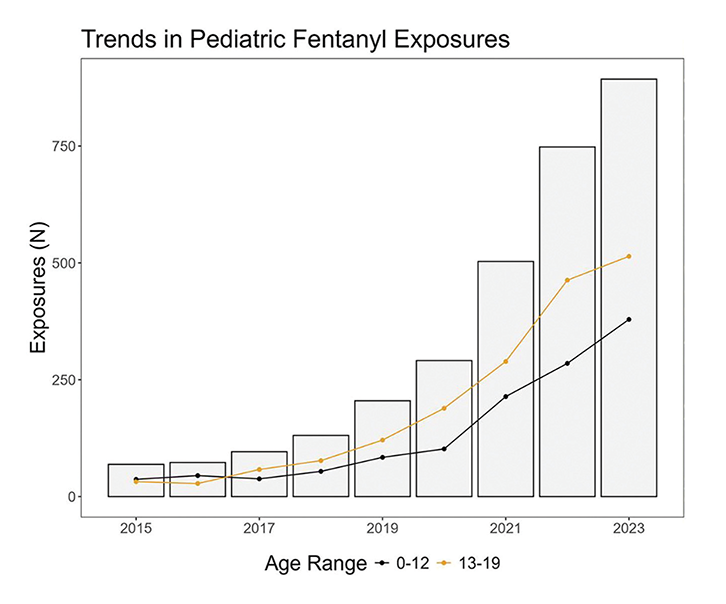

In March, their work revealed that non-fatal exposures to fentanyl among children reported to poison centers grew from 69 in 2015 to 893 in 2023 — a 1,194% increase. The largest jump was among those aged 13 to 19, affecting 514 teenagers in 2023. The plurality of exposures — 3,009 in all — resulted in a major, life-threatening effect. The findings were published in The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. In less than one month, the paper was covered in over 100 news stories, blogs, social media posts and other online sources.

It is among the first analyses examining the prevalence of non-fatal fentanyl exposure among children. The authors say their results show an urgent need for more prevention and harm reduction. Cottler says that includes safely disposing of used fentanyl patches, controlling kids’ access to medications meant for others and educating them about the drug’s dangers. Parents need to be keenly aware of the symptoms of overdoses in children, the authors noted. Even those who use illegal opioids should be well educated about keeping the drugs away from children, they concluded.

“The paper made a big impact because it’s about kids and the ways they can be harmed unintentionally,” Cottler says.

We’re uniquely situated to identify emerging drugs. We want to impact the degree of drug use and mortality by disseminating reliable information.”

—Bruce Goldberger

Next, the NDEWS team is looking to expand the depth and breadth of its work. Cottler says a scholar came from Spain to learn about NDEWS and begin a sentinel network there. Meanwhile, Palamar says NDEWS new networks involving funeral directors, school superintendents and toxicologists will further diversify the team’s stream of insights in near real-time.

Goldberger, the UF forensic toxicologist, notes that NDEWS is the only federally funded, coordinated drug early warning system in the United States. Cottler finds particular joy in mentoring students to conduct primary data collection and contributing to efforts that matter to communities. All of that comes together with NDEWS.

“It is one of the most interesting studies I have ever worked on,” she says.

Sources:

Linda B. Cottler

Professor of Epidemiology

lbcottler@ufl.edu

Bruce A. Goldberger

Professor of Pathology

bruce-goldberger@ufl.edu

Hear the Story

The audio version of this story is available on our YouTube.