Now that a respiratory virus has made us fearful of passing each other in grocery store aisles and caused the masked among us to gaze reproachfully at the unmasked, people have questions about simply inhaling and exhaling.

Suddenly, breathing seems complicated.

“I give 26 hours of lecture just on respiration,” says University of Florida physiologist Paul Davenport, a professor in UF’s College of Veterinary Medicine and a member of UF’s Breathing Research and Therapeutics Center.

What are the risks that go with inhaling and exhaling during the coronavirus pandemic? It depends.

It is difficult for science to weigh in with specific guidance because of the many variables involved, says Scott Powers, a professor in the College of Health and Human Performance and also a member of UF’s Breathing Research and Therapeutics Center.

While the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends 6 feet of social distancing, it’s not like an invisible force field goes up at the 6-foot mark, stopping the virus in its tracks. How you breathe and where you breathe matters, too.

Every Breath You Take

How much we breathe changes as our physical activity level changes. Powers says, in general, the average 70-kilogram adult at rest takes about 12 breaths per minute, inhaling and exhaling about five liters of air – oxygen is moved into the body and carbon dioxide is expired. Moving from inactivity – sitting, for example – to light exercise – walking down a hallway – increases the gas exchange by three times the resting rate, to about 15 liters per minute.

Then there’s exercise. Moderate intensity exercise can increase the breathing rate to 7-10 times the resting rate. During maximum exercise – sprinting with mouth open, chest heaving – the rate can increase to 20-plus times the resting level.

“If you’re in an environment where the virus exists, your risk of inhaling viral particles goes up because of the increased amount of gas you’re bringing into your lungs during heavy exercise,” Powers says.

How you breathe matters, too, Davenport says. Breathing at rest with your mouth closed is a low-velocity event, and the nose directs exhaled air downward. Coughing and sneezing direct air outward with high shear force to move irritants off the airway tubes and into the main airstream to expel irritants from the body. But even a quiet chat allows moisture on the breath to escape, releasing any molecules on the breath into the air.

What’s in a Breath?

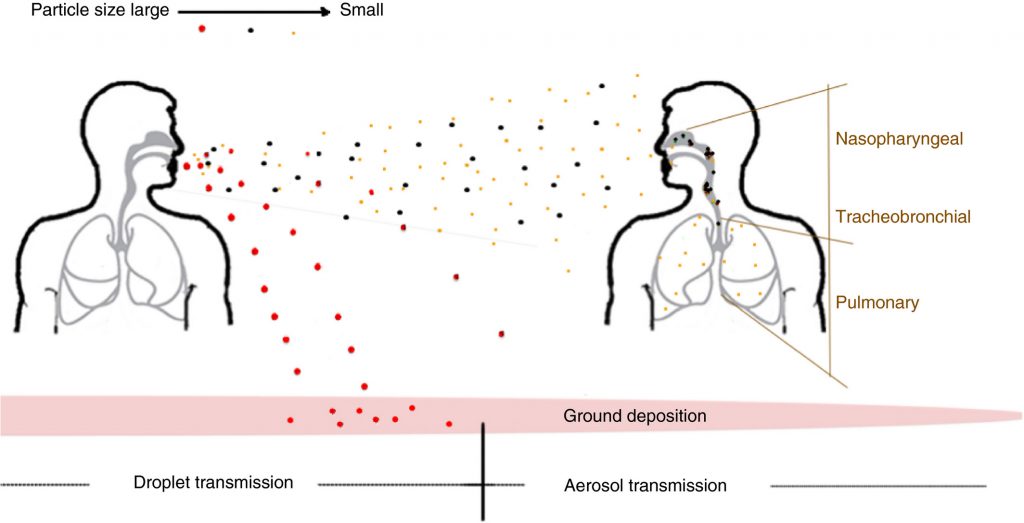

The CDC’s guidance on social distancing is based on how far droplets are thought to travel – 6 feet – but anyone who has been caught in the spray zone of an errant sneeze knows droplets can travel farther.

As soon as droplets leave the body, gravity enters the picture, and droplets begin to sink quickly to nearby surfaces. Once they land, the risk of transmission is not so much breathing as it is contact with a surface contaminated by the droplets.

But exhaled breaths contain aerosols, too, which are much smaller and mostly invisible. Think about cleaning a pair of glasses by breathing onto them and using a cloth. It’s the moist aerosols you see on the lenses. While someone who sneezes might notice exhaled droplets, the aerosols can go undetected along with any coronavirus particles, which are about 0.1 microns. For comparison, a particle of smoke is an order of magnitude larger at 1 micron; a human hair is about 100 microns.

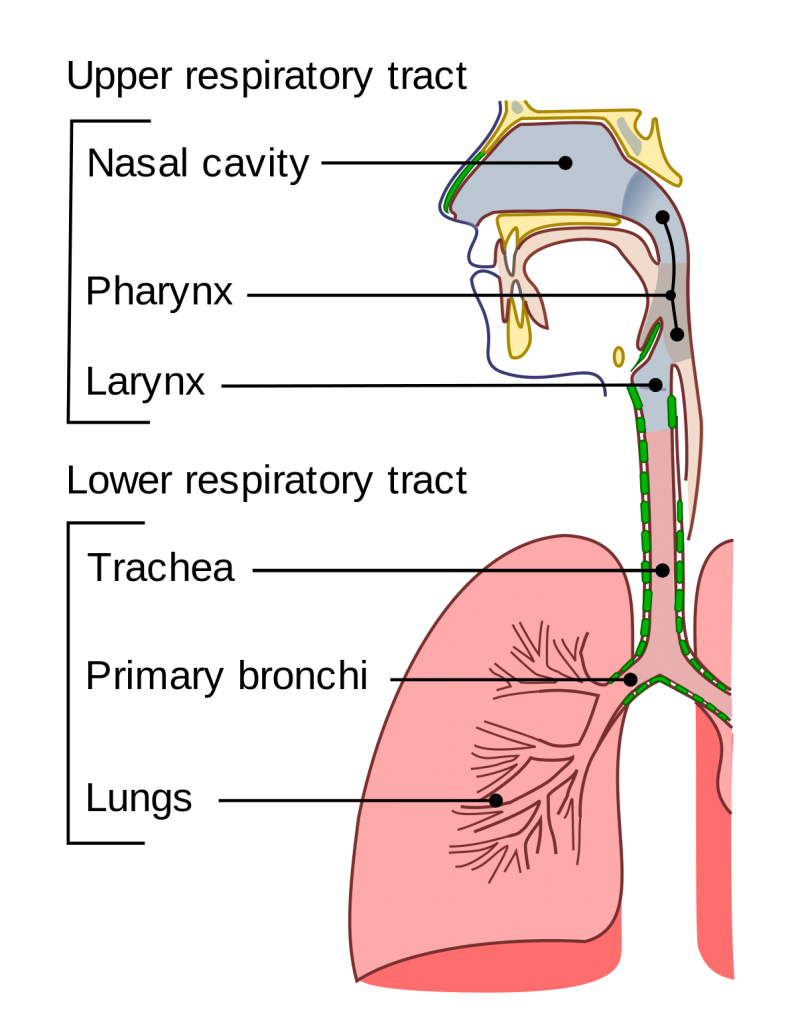

The upper airway, from the nasal cavity to the larynx, does a good job of trapping larger particles that enter. The smaller aerosols, however, can carry viral particles down the trachea to the bronchi and the lungs, causing a more severe infection.

The Environment

Indoor risks with coronavirus are well documented, from nursing homes to hospital wards and even a choir practice in Washington state, where 53 of 61 singers came down with COVID-19.

Outdoors, more social distancing is generally possible, and there is more air movement. The perfume, deodorant or tobacco smoke you smell as you pass someone on a sidewalk or trail is carried to you on the air, along with any invisible molecules in the passerby’s breath.

“If I’m out running, and there’s a breeze, the increased movement of the air is going to increase the movement of molecules that are in the air,” Davenport says.

Powers says if someone is exercising, the volume of expired gas and rate of breathing is going up as well. The exhalation could include viral particles, but depending on air movement, the particles could dissipate quickly, and the short length of exposure to the runner’s breath likely would limit the risk.

“A lot depends on exercise intensity and the way the wind is blowing,” Powers says.

Air flow is good for dispersing particles in the air, but it’s better for the exhaler than the inhaler.

“For you, exhaling is a great thing,” Davenport says. “For the people around you, it’s not necessarily a great thing because that’s how exposure is transferred. If you can catch exhaled droplets with a mask, you can reduce the transfer.”

The Mask

But masks also are not the simple solution they seem to be.

A mask increases resistance to breathing, what physiologists call a load, and that can trigger an adverse reaction.

“A mask is a load,” Davenport says. “It increases your difficulty of breathing, which makes you aware of your breathing. If the awareness gets too high, it can produce fear or even anxiety.”

Most of the process of breathing takes place unconsciously in the brain stem, part of a process in which many bodily functions – blood circulation, breathing, digestion – take place without our attention. When we become aware of breathing, the cortex kicks in, but to humans, the awareness of breathing, called interoception, is a sign that something is wrong. Davenport says one of the top reasons people see a doctor is difficulty breathing. We don’t think about breathing, until we can’t breathe.

“If I put a high-resistance mask on your face, the first thing you’re going to want to do is rip it off,” Davenport says. “It’s escape behavior.”

Breathe In, Breathe Out

Engaging the cortex can also be a good thing, as in airway rehabilitation. Davenport and a team of researchers worked with actor Christopher Reeve, who used a ventilator after a brain stem injury caused paralysis, on respiratory training to strengthen respiratory muscles. Cognitive awareness of breathing can also help you suppress a cough at a movie or a concert, for instance, making you more popular with the people sitting next to you.

Since we can’t hold our breath until a vaccine is developed, engaging the cortex might be the next best thing.

Anecdotal evidence shows that taking control of your breathing as in meditation or yoga can have a calming influence, but it’s a difficult topic to research because of the need for a control group that would be unaware of breathing modification techniques.

“I have no idea why it works, but it does,” Davenport says. “I can actually change my blood pressure by changing my breathing pattern. And think about it. If you’re nervous, what’s the first thing someone is going to tell you?”

Take a deep breath – perhaps a mixed message in a coronavirus pandemic.

Sources:

- Paul Davenport, Professor, UF College of Veterinary Medicine

- Scott Powers, Professor, UF College of Health and Human Performance

Related Website: