The man’s skin just didn’t feel right.

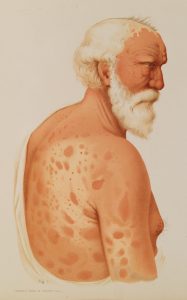

He’d been to four dermatologists before traveling to the University of Florida, where he described patches of skin feeling “loose” — almost dead. The rash that covered his torso and limbs in reddish-purple spots hadn’t responded to the steroids and antibiotics the previous doctors prescribed. Worse, his legs felt hot and swollen, tingling with what felt like electrical shocks, and the loss of feeling in his feet was spreading to his arms.

Despite the fact that the man’s only international travel had been a cruise 15 years prior, his UF Health dermatologists consulted with their colleagues in the Division of Infectious Diseases and Global Medicine. The physicians suspected something ancient — Biblical, even.

If you thought leprosy was eradicated long ago, you’re not alone. But each year, more than 200,000 people worldwide are diagnosed with the condition now known as Hansen’s disease, a bacterial infection that can cause irreparable damage if untreated. The United States averages fewer than 200 cases per year, with 6,500 active cases on the National Hansen’s Disease Programs Registry, but Florida has one of the highest rates of infection — and experts say cases are on the rise here and nationally. In 2023, UF launched a research team to mobilize against humanity’s oldest infection, which remains as shrouded in mystery as it is in stigma. The team aims to tackle both.

“Why does Florida have so many cases of Hansen’s? And are we just the tip of the iceberg?” asks Dr. Norman Beatty, an infectious disease specialist at UF’s College of Medicine who advocated to create the team. “We can really dive into some groundbreaking research here that can be translated to other regions.”

Beatty specializes in what are known as Neglected Tropical Diseases, understudied conditions that the developed world may no longer have the luxury of neglecting.

“As a scientific community, we really have to acknowledge that certain diseases have been put on the back burner, and Hansen’s is one of them,” Beatty says. “As our state continues to change, as our environment and climate changes, diseases like Hansen’s will continue to evolve. Without doing the research that’s needed, we’re not going to understand who’s at risk.”

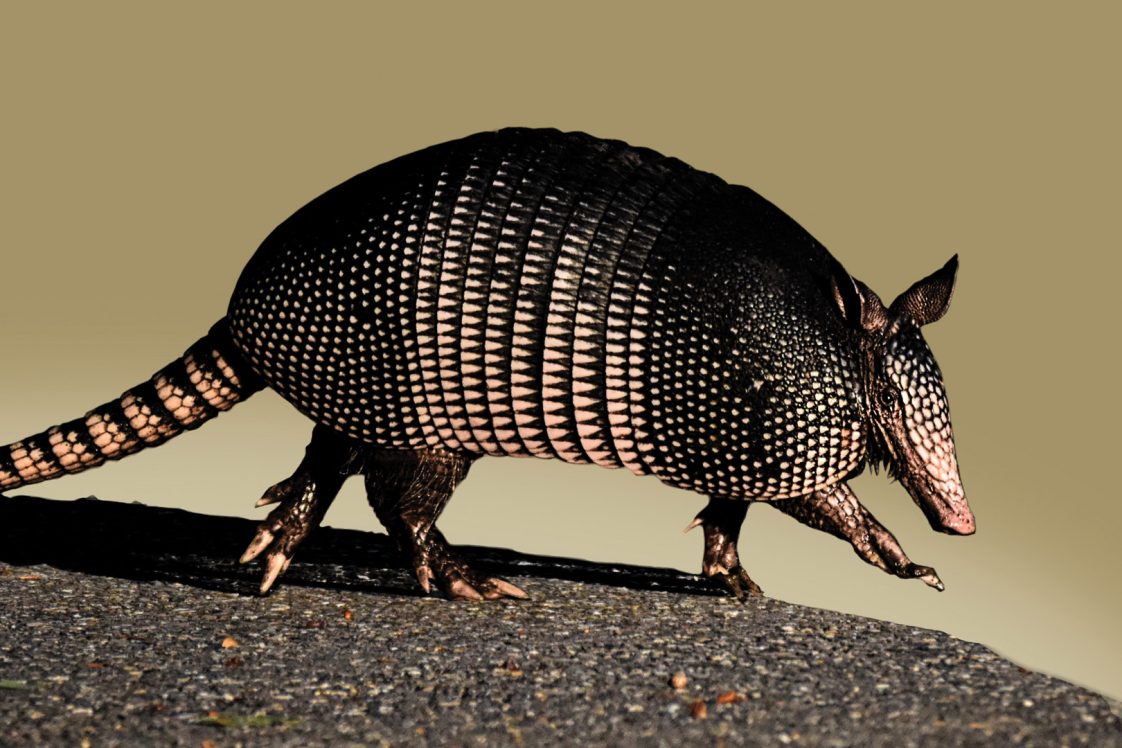

For the patient with the loose-feeling skin, the screening hinged on an unusual question: Had he had any contact with armadillos?

What is Hansen’s disease?

Dr. Kartik Cherabuddi lifted his student’s forearm, tapping it gently with the tip of his pen. The red patch that bloomed there brought him back to his time in medical school in southern India, where he’d seen “more cases of leprosy than I can remember,” he says.

Now he’s seeing cases here.

Luckily for the student, this isn’t one of them. Cherabuddi drew the lesion on the student’s arm with a marker about an hour ago, before a symposium on Hansen’s disease organized by UF’s Emerging Pathogens Institute. Standing at the front of the amphitheater, he demonstrates how to test for the loss of sensation that typifies the disease as the assembled crowd of physicians, researchers, patients and curious members of the public looks on.

Hansen’s takes on average more than eight months to diagnose in the U.S., where leprosy isn’t top of mind for most doctors. It’s highly curable with antibiotics, but the lost time can translate to nerve damage that endures after the infection abates. Like tuberculosis, Hansen’s is caused by a bacterial infection — they’re even in the same mycobacterium genus. When Mycobacterium leprae takes hold, it not only causes skin lesions but attacks the nerves. That’s the root of leprosy’s association with lost body parts: Once patients can’t feel pain in the affected areas, it’s much easier to get injured and re-injured, especially in vulnerable areas like fingers and feet.

While more than 95 percent of the population is thought to be naturally resistant to M. leprae, throughout history those with leprosy were forced into lifelong isolation for fear of the disease’s spread. Leper colonies aren’t just the stuff of distant lands or medieval tales. In the U.S., admissions to the National Leprosarium in Louisiana didn’t become voluntary until the 1970s, with treatment shifting to outpatient clinics in 1981.

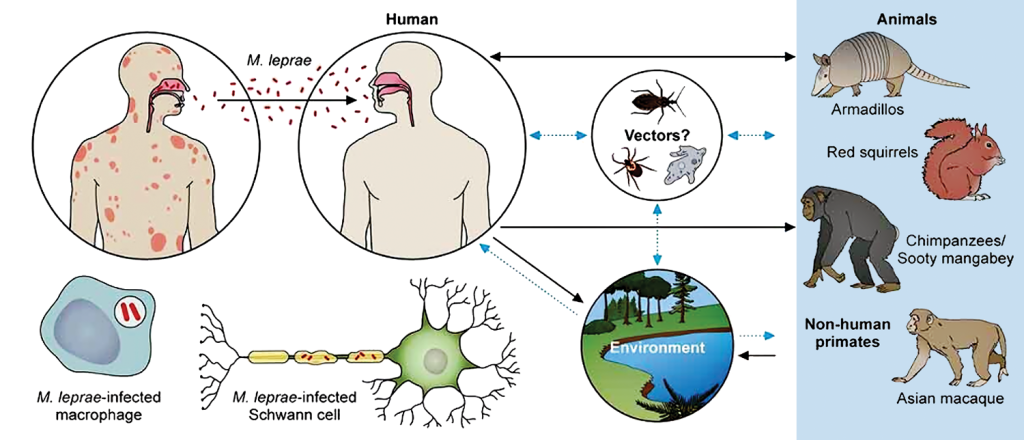

Were these extreme measures necessary? While current knowledge says person-to-person spread requires close, sustained contact, Cherabuddi and Beatty wonder if Hansen’s is actually spread in another way, especially in the U.S. During Cherabuddi’s medical-school rotation in a leprosy clinic, he often saw households with more than one person affected, but that’s not the case in the States. Could the family connection in other countries be due to other factors households share, like soil, water, genetics or nutrition?

“I think there is more to the story,” Cherabuddi says. “Even though it’s the oldest infectious disease known to mankind, there’s so much still unknown.”

First, they need a stronger grasp of the disease’s prevalence, Cherabuddi says.

“How common is it in Florida? The scope of the problem is the first thing to understand,” he says. “Everything else flows from there.”

What they already know is that early diagnosis is key to making a complete recovery. At the symposium, Cherabuddi teaches physicians in the audience to look for nodules in cooler areas such as ears that the bacterium prefers and to feel patients’ nerves for the thickening that’s a telltale sign of the body trying to contain the invading bacteria.

That’s what the UF team did for the man who had struggled for years with his mysterious symptoms, noticing that a nerve in his leg was enlarged — which brought them back to armadillos, the only known animal host of Hansen’s in the Americas and a possible player in its spread. Ten years ago, his neighbor had asked for help removing armadillos burrowing under her house. He had obliged.

We had it first

Spare a thought for the armadillo, scratching out an existence in ever-smaller stretches of wilderness, much of it bordering our backyards. Then consider that while armadillos could be giving us leprosy now, we gave it to them first. They even develop the same symptoms. Scientists aren’t sure how leprosy spreads among armadillos or from armadillo to person. They have no idea how many armadillos live in Florida, let alone how many carry M. leprae — but in areas like Brevard County, the epicenter of recent cases, testing indicates it could be a quarter of them.

Some Hansen’s patients in Florida have had direct contact with armadillos, like a man who accidentally ran one over with his riding lawn mower. The resulting mess sprayed armadillo blood and bits onto his leg, where he later developed a lesion that turned out to be Hansen’s. Others may have had exposure to bacteria in the soil through jobs like landscaping, says Dr. Juan Campos Krauer, a UF veterinarian who brings wildlife expertise to the Hansen’s team. An avid gardener, Campos Krauer takes precautions to avoid the bacterium, but when he sees armadillos snuffling around his compost pile, he’s not alarmed.

“They’re essentially harmless,” he says. “They’re also beneficial. They’ll eat spiders, they’ll eat cockroaches. Really, I don’t think people need to go to war with armadillos. Just make sure to wear gloves, or wash your hands thoroughly. Change clothes if you were working with lots of dust and dirt, and change your shoes or at least clean them before going inside.”

In his native Paraguay, the connection between armadillos and leprosy is common knowledge.

“The first day I arrived here in Florida, I started driving and was seeing all these dead armadillos around on the side of the road. I was thinking, wow, it would be super interesting to collect these animals and test them to see if they’re positive.”

Now he’s doing just that, in Gainesville and four surrounding counties. He wants to find out how widespread Hansen’s is in armadillos — and if roadkill can spread it into the surrounding soil and water. After collecting an infected carcass, he’ll place it in a controlled field environment protected from flies and predators, then sample it every six hours for two or three weeks to see how long the leprosy bacillus remains viable. Armadillos tend to stick to the same paths and passageways, and males follow females’ pheromone trails during mating season. If the bacteria endure after the host dies, that means goop on the roadside could infect more armadillos walking through it. Campos Krauer’s findings can inform control measures, such as barriers in key areas, that could reduce roadkill risk. With enough data, the team can also identify areas of high positivity where such control measures are most needed, he says.

His first challenge: finding carcasses. While there’s no shortage of squashed armadillos, in the race to collect them, vultures often get there first. While vultures are not known as leprosy hosts — other than armadillos, only primates and red squirrels carry the disease — Campos Krauer wonders if the feet and beaks of feasting vultures could spread the bacteria.

“I would love to test vultures, too,” he says, “but that’s more challenging.”

A new strain?

Before you swear off the outdoors, keep in mind: Most people who are exposed to leprosy won’t become ill, and many of those who do likely recover on their own. It’s incredibly rare. So why did UF form a Hansen’s team?

“When leprosy started appearing in the media, people thought there was a sudden change,” Cherabuddi explains. “It’s more a subtle change that’s been going on for a few years now. Once we see escalating numbers of infectious disease, you might see a much larger outbreak later. When an epidemic happens, you see numbers slowly creep up and then there might be an explosive phase. If that’s going to happen, you’d want to be informed beforehand.”

Part of what concerns scientists is leprosy’s leisurely timeline. You could be exposed now, but not develop symptoms for a decade, when it’s hard to remember specific situations where you might have encountered the bacterium. (Unless you liquefied an armadillo with a lawn tractor. Nobody’s going to forget that.) If the cases popping up now originated five or 10 years ago, how many will we see 10 years down the road?

Another challenge: M. leprae has never been successfully grown in a lab. That complicates its study, but not its cure — the right antibiotics will kill it, and if it’s not too advanced, reverse the lesions and nodules it causes. Still, Hansen’s carries a stigma that more-contagious diseases don’t.

With Hansen’s in the headlines and in our backyards, there’s new urgency to find answers about its spread. Cherabuddi and Beatty hope that UF’s research capabilities, including detailed genetic analysis, can make strides to eradicate the ancient disease.

“What is interesting here in Florida is, it’s impacting a whole wide breadth of folks from different backgrounds and scenarios. We really do not know why certain populations are at risk and why certain populations are becoming infected,” Beatty says. “Who should we be screening? How do we develop programs for access to the care and the testing that’s needed? We really have none of that right now.”

The UF team will look at what makes people resistant to the bacteria. They’ll also study de-identified blood samples to check for antibodies to Hansen’s to estimate how many people have been exposed, and investigate whether those who are infected are transmitting the bacteria within their households, which has never been studied in the U.S. Following the discovery of a second species of leprosy bacterium in Mexico in 2008, Beatty wonders if yet another strain might be causing Florida’s cases. Genetic sequencing can shed light on that possibility, which could inform prevention and treatment, drawing on partners across campus and beyond.

“To tackle a complex disease like this, we need molecular biologists, we need wildlife specialists, we need environmental scientists,” Beatty says. “That’s why I enjoy working at the University of Florida. It’s a culture of team science.”

The UF team found answers for the man with the dead-feeling skin, in partnership with the National Hansen’s Disease Program. It was clear he had leprosy. After a month on anti-inflammatories, he started a regimen of three antibiotics. After six months, his lesions were barely visible. In two years, he no longer had leprosy, but his nerve pain continued.

“Once the nerves are damaged,” says Dr. Nicole Iovine, UF Health’s chief hospital epidemiologist, “it’s permanent.”

The takeaway? Early diagnosis is key. If you have lesions you think could be leprosy, talk to your doctor —and steer clear of armadillos.

Sources:

Norman L. Beatty, MD

Assistant Professor of Medicine

norman.beatty@medicine.ufl.edu

Kartik Cherabuddi, MD

Professor of Medicine

kartikeya.cherabuddi@medicine.ufl.edu

Juan M. Campos Krauer, DVM, PhD

Assistant Professor of Large Animal Clinical Sciences and Wildlife Ecology and Conservation

jmcampos@ufl.edu

Hear the Story

The audio version of this story is available on our YouTube.