When Robert Lucero’s great-grandmother fell at home and fractured her hip, it set off a rapid decline in health that left her dead within days.

That experience ignited a passion in Lucero, a UF College of Nursing associate professor, to ensure that other families do not have to suffer the same experience, especially while their loved ones are hospitalized.

Falls are the most common type of hospital-acquired illness, also known as iatrogenic conditions. In the United States, between 700,000 and 1 million falls occur in hospitals annually, resulting in an estimated $50 billion in medical costs.

Lucero has dedicated his career to identifying factors that contribute to hospital-acquired falls and figuring out how to reduce or eliminate them.

“As nurses, it is our responsibility to be the surveillance system for patients to maintain their safety when they are hospitalized,” Lucero says. “People like my great-grandmother are vulnerable to the environment they are in when they are hospitalized. The responsibility of the health care provider is to ensure the patients’ safety, because consequences can be emotionally and physically debilitating, as well as even life-threatening.”

Lucero and College of Nursing Assistant Professor Ragnhildur I. Bjarnadottir believe answers to preventing hospital-acquired falls can be found in nurses’ progress notes, unstructured data within electronic health records, or EHRs, that is not commonly examined but that they believe can be analyzed using text-mining and data science to reveal new fall risk factors.

As nurses, it is our responsibility to be the surveillance system for patients to maintain their safety when they are hospitalized.

Robert Lucero

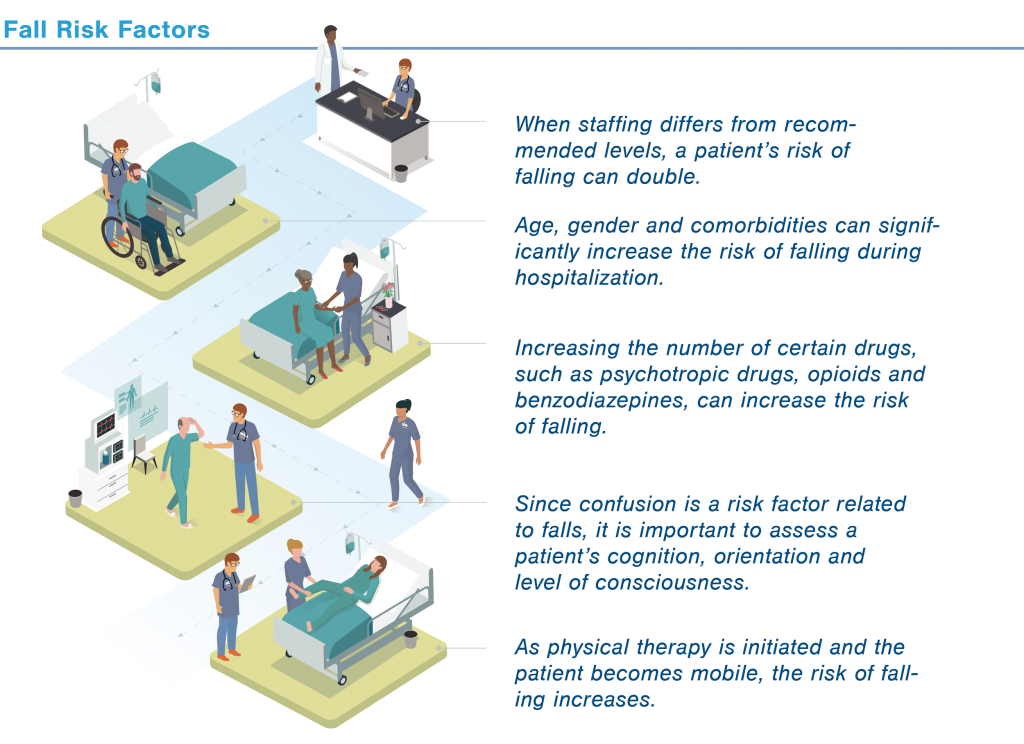

Lucero and his colleagues started their research by focusing on structured data within patients’ EHRs – like their blood chemistry and the medications they were taking. They compared the EHRs of adult patients who experienced a fall during hospitalization to those who did not and identified several new factors that influence the risk of falling, including hemoglobin level, severity of illness, the number and types of drugs taken and the need for physical therapy, as well as the nurse skill mix and staffing. Based on these results, his team developed an educational infographic to guide nursing staff, families and patients toward reducing hospital-acquired falls.

But as much as 80 percent of electronic health data is unstructured text – like nurses’ progress notes. These can be a rich source of information because RNs routinely record narrative observations and assessments of patients and their environment. The process of analyzing narrative text data is complex, but it is critical to identifying patterns and attributes associated with hospital-acquired falls and hospital-induced delirium, Lucero says.

Using a five-year $2.57 million grant from the National Institute on Aging, Lucero and Bjarnadottir and their team are tackling this unstructured data to develop ways of predicting injury and death related to hospital-acquired conditions such as falls and delirium.

Lucero, Bjarnadottir and researchers and clinicians from across UF Health are developing UF EHR Clinical Data Infrastructure for Enhanced Patient Safety among the Elderly, or UF-ECLIPSE. They are analyzing data collected over six years from more than 130,000 patients and more than 2 million progress notes.

Among the conditions that can contribute to a hospital-acquired incident are a patient’s mental status and/or medications; environmental factors, such as unfamiliarity with surroundings or clutter that could pose as a trip hazard; and clinical/organizational interventions, which can either be preventive or increase risk. To process nurses’ progress notes to predict hospital-acquired falls, the researchers are using algorithms and analytics to identify word clusters or patterns in the data that include these factors.

This NIH award demonstrates the strength of nursing and health informatics at the University of Florida.

Anna M. McDaniel

“The potential impact of this project is substantial,” Bjarnadottir says. “There is so much that we still do not know about how to predict and prevent iatrogenic conditions, but this project can support countless data-driven interdisciplinary aging studies and become a piece of the data science infrastructure necessary to fuel a learning health system. This is, therefore, a significant building block in our quest to find ways to reduce and perhaps eventually eliminate iatrogenic conditions among the growing number of hospitalized older adults in the U.S. and around the world.”

Nurses are known to be the heart of the health care system, with demonstrated abilities to collaborate and identify the need for patient advocacy and access, says College of Nursing Dean Anna M. McDaniel. Faculty at the College of Nursing are being recognized for their groundbreaking research and innovative solutions to solve specific problems facing health care today.

“This NIH award demonstrates the strength of nursing and health informatics at the University of Florida,” McDaniel says. “It will also continue to chip away at a historically siloed approach to understanding complex clinical problems by having interdisciplinary teams tackling and identifying solutions through nursing science, clinical informatics and data science.”

Her Heart Genes

As a doctoral student at the UF College of Nursing in the early 2000s, Jennifer Dungan regularly biked to the UF Health Shands Hospital carrying a biohazard cooler to collect and study human coronary artery fragments removed during heart bypass surgeries. Dungan used the tissue in her doctoral research to determine whether certain genes were expressed differently among people without high blood pressure.

After spending the last decade at Duke University, Dungan has returned to her alma mater as an associate professor to continue her groundbreaking genetic research, which has already identified genetic markers that predict different outcomes for women and men with heart disease. Women with certain genetic markers were found to have a higher risk of acute heart disease and also poorer survival rates compared to men.

Dungan has looked at variations across one million genetic markers and found a completely different group of markers that predict death among women and men. In addition, when women seek medical help for heart disease, they are more likely to fall into a medium risk category, so they are deemed OK to return home and instructed to follow up with a cardiologist. However, one in five of these women actually dies within 30 days because the severity of their symptoms were not taken seriously or not articulated adequately, and their cardiac evaluation was not as definitive.

“Most people think we have the same heart and the same risk factors, like poor diet, that contribute to heart disease,” Dungan says. “But heart disease can look differently among women for different reasons, like biology, physiology and the experience of atypical symptoms. This finding is significant because every diagnostic method we use right now is based on research conducted on white males.”

My passion is trying to find an objective bio marker that is more predictive of women’s heart disease, so we do not have to rely on an individual’s report of their symptoms, which can be internalized and experienced differently.

Jennifer Dungan

She adds that a new line of questions have opened up for her since identifying these genetic patterns among men and women.

“As exciting as this discovery is, as a scientist what keeps me awake at night is finding a way to help the millions of women out there with unrecognized symptoms, or those who struggle to get the cardiac care they need. Right now, I cannot go any further without answering two questions: Are these genes also a factor for women in racial minority groups? And do these genes play an important role during the postmenopausal phase, when many women are at higher risk for heart disease?”

In particular, Dungan is studying the genetic variations of postmenopausal and African American women, because those groups experience the most health disparities with heart disease.

“My passion is trying to find an objective bio marker that is more predictive of women’s heart disease, so we do not have to rely on an individual’s report of their symptoms, which can be internalized and experienced differently,” Dungan says. “If we were to have an objective, female-specific bio marker, we would stand a chance to reduce those one in five women who die within 30 days of their initial evaluation.”

UF College of Nursing Dean

McDaniel says diversity is one of the core values of the College of Nursing.

“Our researchers are immersed in a global world in which science can serve as the adhesive to not only solve specific problems, but to bring us all together as a population,” McDaniel says. “Genetic research across various ethnicities and subgroups, such as Dr. Dungan’s, is vital to our collective effort to advance health care for all.”

Overcoming Stigmas

Receiving a cancer diagnosis is hard enough, but even after treatment many women with breast cancer experience decreased quality of life, fatigue, depression and memory loss, and they are often told these symptoms are all in their heads.

College of Nursing Associate Dean and Professor Debra Lyon has spent the last 20 years identifying objective measures that may illuminate new pathways for treating distressing symptoms in cancer survivors. As a psychiatric nurse, her interest in breast cancer research stems from the desire to understand the stigma breast cancer patients and survivors face when encountering these conditions.

“Breast cancer patients and survivors may be told that feeling tired and not feeling well is all in their head,” Lyon says. “As nurses, we are always trying to push through the stigma that these common distressing symptoms and conditions are not considered as physiologically based as other conditions. My aim is to discover physiological pathways that lead to developing new therapies to cure the disease and additional long-term consequences and side effects.”

UF College of Nursing Associate Dean and Professor

Lyon’s research is concentrated on the “-omic” fields of biological sciences, such as genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics or metabolomics.

Her current work focuses on -omic measures of blood markers and their association with outcomes. This includes the intersection of biology, symptom manifestations and quality of life, primarily for women with breast cancer.

Two recent studies published in the journals Epigenetics and the Journal of Neuroimmunology highlight the association of sophisticated blood markers with patient-oriented outcomes of depression, fatigue and cognitive dysfunction, including memory impairments. Lyon found that changes in cytokines — proteins that signal communication among cells — during chemotherapy contribute to symptoms of fatigue among breast cancer patients.

Personally, I love the science behind my research in cancer, but I find the opportunity to support and establish the next generation of researchers very rewarding…

Debra Lyon

Lyon’s other focus is on expanding the pipeline of minority students who will form the researchers and clinicians of the future and help eliminate health disparities in cancer. As the director of the Research Education Core at UF for a five-year, $16 million grant from the National Cancer Institute to establish the Florida-California Cancer Center Research, Education and Engagement (CaRE2) Health Equity Center, Lyon works with other researchers from this multi-site project to support translational cancer research and training among minority populations.

“Individuals always prefer to see providers with shared cultural understanding,” Lyon says. “By building the pipeline of minority researchers and clinicians, we are increasing the multicultural understanding and outcomes of cancer in populations experiencing health disparities, and we are accomplishing it in a way that is culturally congruent. Personally, I love the science behind my research in cancer, but I find the opportunity to support and establish the next generation of researchers very rewarding, especially as it relates to expanding the diversity and experiences through minority researchers.”

Sources:

- Ragnhildur I. Bjarnadottir, Assistant Professor of Family, Community and Health Systems Science

- Jennifer R Dungan, Associate Professor of Biobehavioral Nursing Science

- Robert Lucero, Associate Professor of Family, Community and Health Systems Science

- Debra Lyon, Executive Associate Dean and Professor of Nursing

Related website: