The woman in the UF Health Jacksonville emergency room presented a puzzle for attending physician Faheem Guirgis. In her early pregnancy, she had a sore throat and a fever. Those symptoms were not alarming compared with those of other patients being seen on that busy day, but Guirgis had a feeling that something wasn’t quite right with her.

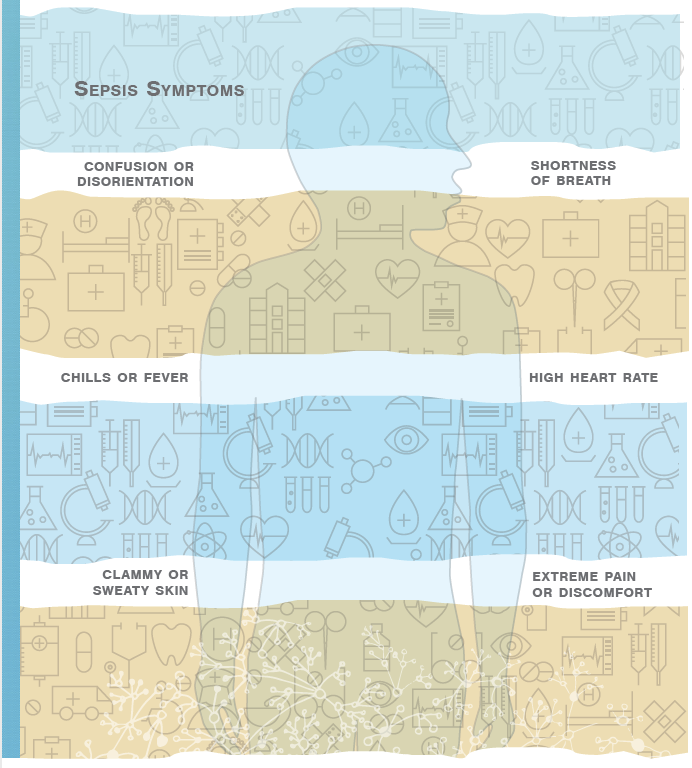

He ran routine lab tests, which came back “a little off,” he says. Guirgis handed her care over to the next shift, but overnight the woman’s condition deteriorated, and she went into shock. The expectant mother, it turned out, was septic. The nation’s third-leading killer, sepsis is a complication in which the body has a severe, overwhelming response to an infection.

Guirgis says that if he had access to a test for a sepsis biomarker, he could have diagnosed the sepsis before her symptoms emerged.

“If I had known she was septic when I saw her in the beginning, I would have done things a bit differently up front,” says Guirgis, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at the UF College of Medicine — Jacksonville. “I would have been able to discern more clearly.”

Ultimately, the woman recovered and was discharged from the hospital with an ultrasound of her healthy baby. But the July 2015 case demonstrated to Guirgis the need to better connect research into areas such as sepsis with his clinical work.

Thanks to an innovative program at the University of Florida, Guirgis and other early-career researchers now are marrying those aims in ways that not only help them develop their careers but could also become a model for fostering research at hospitals across the country that have large, underserved patient populations.

Guirgis, 36, is among those physicians who combine their passion for working with patients with a deep interest in looking into the “why” of diseases. “I come from the clinical world with scientific questions,” he says. “How can I improve the quality of care for my patients?”

Scientific research helps clinicians better treat patients, and clinicians have practical experience treating patients that researchers in the lab do not. The UF Clinical and Translational Science Institute, or CTSI, seeks to bridge these two worlds. Through a variety of programs and services, the CTSI speeds the transition of scientific discoveries ‘’from bench to bedside.’’

The CTSI is one of more than 60 research institutions nationwide that receive funding through the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, or NCATS. The center offers programs, including the Clinical Translational Science Award, or CTSA, which help clinicians develop research careers.

But clinicians at satellite campuses, even if they are at large urban hospitals such as UF Health Jacksonville that are affiliated with a nationally ranked academic institution, can face barriers to doing research.

Public hospitals in big cities see lots of patients: UF Health Jacksonville handles more than 90,000 emergency department visits and more than 5,000 traumas each year. This provides opportunities for research, but these hospitals often lack the research resources and support to make them competitive for NIH grants to support that research.

Physicians such as Guirgis often face a choice: Leave their public hospitals and the patient populations they are devoted to serving and move to an institution with a more robust research infrastructure, or stay and try to find some way to advance their research goals.

Overcoming Obstacles

“I’ve always been fascinated by the biology of disease,” Guirgis says. “When I took this job, I had no idea I wanted to do research. As I started to take care of sepsis patients, I started to have a lot of questions.”

Guirgis’ interest in research led him to Thomas A. Pearson, UF Health executive vice president for research and education. Pearson recognized the intellectual hunger in Guirgis.

“I’ve been at a variety of academic health centers and rural teaching hospitals, and there are others like Faheem throughout those institutions,” says Pearson. “It’s part of our job to identify them and say, ‘Is research something you want to do in your career?’ The CTSA is the ideal vehicle for that because you want to link basic science with clinicians, and that’s Dr. Guirgis’ story.”

“I’m just kind of an inquisitive person,’’ Guirgis says. “I didn’t realize it but I probably wanted to be a researcher all along.’’

Pearson urged Guirgis to apply to the “K College,” which Pearson launched several years ago as an informal lunchtime discussion among early-career researchers and clinicians who were interested in doing translational research. Part of the CTSI Translational Workforce Development Program, the K College prepares participants to apply for the CTSI’s KL2 Scholar Multidisciplinary Program, which provides two years of financial support and helps faculty develop collaborative careers in clinical and translational research. The K College now has 182 participants.

Guirgis also began working with his main mentor, Dr. Frederick Moore, a professor of surgery at the UF College of Medicine and the principal investigator of the UF Sepsis and Critical Illness Research Center.

The first of its kind in the nation, the center was created with a $12 million, five-year grant from the NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences in 2014.

The center serves as a tool to promote collaboration and enables young faculty to garner additional NIH funding, Moore says.

“It plays the unique role of developing young investigators who absorb the cultural and scientific philosophies of team science that cannot be gained by working in a typical return-on-investment, RO1-funded, investigator lab,” he says. “Not only are they mentored by older, more established physician-scientists, but they frequently have close interactions with basic health scientists, biomedical engineers, biostatisticians, computational biologists and medical ethicists.”

Guirgis’ co-primary mentor is Christiaan Leeuwenburgh, director of the UF Division of Biology of Aging, who also serves on the directorate of the CTSI Translational Workforce Development Program.

Other mentors included Lyle Moldawer, a professor and vice chair of research in the UF College of Medicine’s Department of Surgery; Dr. Sunita Dodan and the late Dr. Robert Wears; Srinivasa Reddy of UCLA; and Dr. Alan Jones of the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Guirgis honed his research skills at the sepsis center and was accepted into the KL2 Scholar Multidisciplinary Program, becoming the first Jacksonville-based physician to participate in the program.

In September, Guirgis landed a four-year NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant to pursue sepsis research. The grant will allow him to develop a satellite lab at the UF College of Medicine at UF Health Jacksonville, where his research team can explore how sepsis affects patients in the Jacksonville region.

“Dr. Guirgis is a great example of how interested clinicians at satellite campuses can benefit from the support, mentoring, resources and career development of a CTSA hub,” Pearson says. “Not only that, his experience shows how we can foster research at clinical sites with large and underserved patient populations like Jacksonville.”

The cycle of research and discovery is continuing: Guirgis’ new grant freed up his spot in the KL2 program, providing grant funds for another early-career scientist to enter the program.

Guirgis’ journey demonstrates a new model for developing paths to research careers, says CTSI Director David R. Nelson. “Instead of a single investigator finding a mentor and developing a K award, we have these multidisciplinary teams linking around a disease area,” Nelson says. “It fosters a great opportunity to bring in young faculty for productive pathways in training development.”

It’s the kind of team science and research ecosystem the CTSI aims to build, he says.

And it strengthens the ties between the UF Health teams in Gainesville and Jacksonville.

“I see clinical research as part of quality health care, and I believe that patients need access to both,” Guirgis says. “UF Health Jacksonville needs access to the UF CTSI in Gainesville, which has access to the resources needed for an NIH career.”

Underserved Populations

Access to research is doubly important for underserved populations such as those in and around Jacksonville, which is poised to become a majority minority city: 55 percent of its youngest residents are members of a minority group.

Minorities also tend to be underrepresented in health research. Although 40 percent of Americans belong to a racial or ethnic minority, individual research studies often don’t recruit groups of participants that reflect the diversity of the groups of patients who ultimately will take the medication or use the therapies that result from that research. The same medication might work differently in people with different genetic makeups, compounding the problem when research studies tend to recruit more white participants.

When clinicians working at hospitals such as UF Health Jacksonville conduct research, it’s easier for more patients who are members of minority groups to participate because the research is being done where they already go for health care.

CTSI programs also seek to promote diversity among the researchers themselves, overcoming another barrier to research-participant recruitment.

The statewide OneFlorida Pragmatic Clinical Trials and Implementation Science Minority Education Program, or MEP, partners with historically black colleges and universities. Junior faculty members receive hands-on research experience by partnering with faculty members affiliated with the OneFlorida Clinical Research Consortium, led by the UF CTSI in collaboration with its CTSA partner Florida State University and the University of Miami Clinical and Translational Science Institute. This program is made possible by the James and Esther King Biomedical Research Program.

Funding also helps clinicians such as Guirgis overcome a chief obstacle to conducting research: The demands on their time. Participants essentially buy back the time they would normally devote to clinical practice and put that time toward research.

“That meant research could be more than a hobby,” Guirgis says. “Once you have protected time for research, it overcomes a barrier.”

Even the initial step of devoting personal time to research is not something many clinicians can do.

“Faheem is execeptional in that he gave of his own time to work his way out of the clinic,” Leeuwenburgh says. “It doesn’t happen too often. It’s a wonderful story.”

Guirgis has helped propel initiatives in Jacksonville, Leeuwenburgh says. And his research is already showing results. Guirgis says his team has demonstrated for the first time that sepsis patients often have high levels of “dysfunctional HDL,” or high-density lipoproteins, in their blood.

They want to find out whether dysfunctional HDL, a kind of cholesterol, can predict chronic critical illness, an intensive care unit stay of greater than 14 days with organ dysfunction, or long-term adverse outcomes after sepsis. Chronic critical illness has become a common problem in sepsis patients, and results in decreased quality of life and eventual death. Research into chronic critical illness is being spearheaded by Moore and Moldawer at the Sepsis Center.

Guirgis’ study has enrolled patients in Jacksonville and Gainesville. His team will compare a cohort of emergency department patients (who have “community-acquired” sepsis) with a cohort of patients who developed sepsis after having surgery (“hospital-acquired” sepsis), looking at the differences between these two kinds of sepsis and the role of dysfunctional HDL. His ultimate goal is to develop lipid-based therapies for sepsis.

Guirgis says his interest in research has not taken away from his work with patients. Doing this research “has absolutely informed my clinical practice,” he says.

An example: The national definitions for sepsis recently changed to include a Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, or SOFA, score to predict outcomes in sepsis patients. Guirgis had already been using the SOFA score as part of his research for over three years.

Guirgis sees that his research is inextricably woven into his passion for clinical care.

“I like taking care of really sick people and turning them around,’’ he says. “Why do some people get better, and some don’t? It’s the central question of personalized medicine.”

Photo Credits: Mindy Miller

Source:

- Faheem W. Guirgis, Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine

This article was originally featured in the Fall 2017 issue of Explore Magazine.