In August 2017, architecture Professor Martha Kohen was teaching Resilience of the Caribbean Islands, a graduate seminar. She started her classes with a roundtable discussion of current events, something she calls the World News Café, an idea she borrowed from sociology.

“We do it every class for 15 minutes or so, and students bring interesting outlooks that can be applied to the class,” says Kohen. “It gets us out of the ivory tower and more linked to what’s going on in the world.”

On Sept. 26, a month into the semester, the news was bleak. In the week since the last class meeting, Hurricane Maria had hit Puerto Rico. Even the earliest reports from the island indicated the direct hit from the category 4 hurricane was a humanitarian disaster of historic proportions. Overnight a society crumbled: electricity, communications, food, water and infrastructure disappeared.

As the class talked, an idea emerged: Puerto Rico is so close – hop a plane in Florida at lunchtime and you could have dinner in San Juan – wasn’t there something the University of Florida could do?

Kohen thought so and took the lead, making connections across campus, and weeks later, UF hosted displaced Puerto Rican students and faculty. Then at semester’s end, UF’s Center for Hydro-generated Urbanism hosted a conference on campus, led by architecture Professor Nancy Clark, focused on tropical storms as a setting for adaptive development and architecture. But Kohen knew the best way for her students to help Puerto Rico – and learn at the same time – was to put boots on the ground.

When she organized Puerto Rico Re_Start for the spring semester, all the students wanted to go.

“Everyone saw an opportunity to make a difference,” Kohen says. “Everyone wanted to help.”

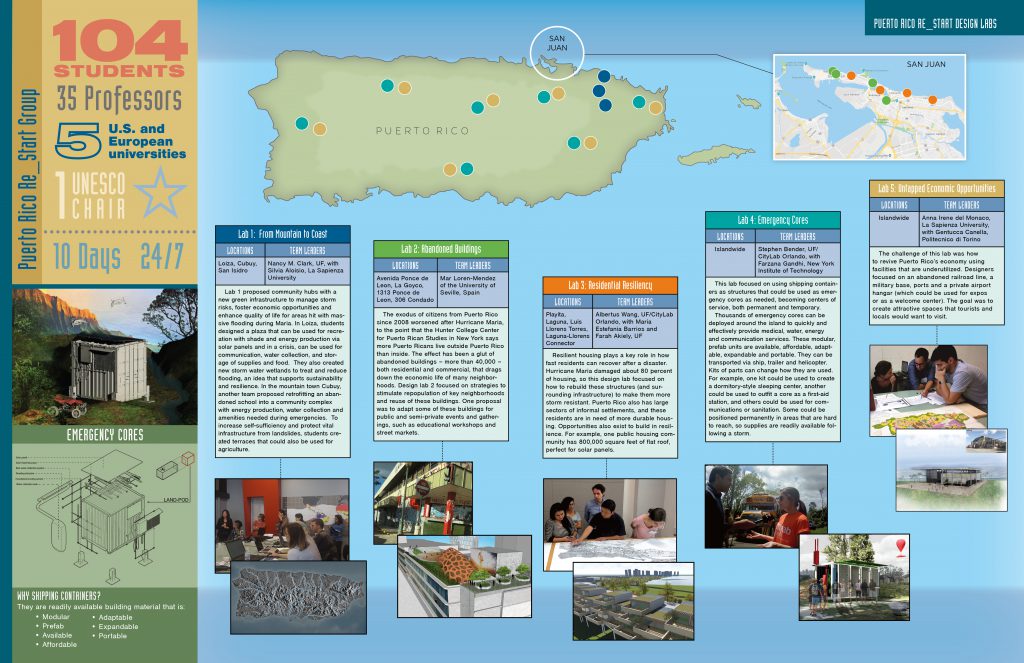

Kohen cast a wide net in her call to action, leveraging her international contacts, and by March, a small army of 104 students, 35 professors, five U.S. and European universities and one UNESCO chair had teamed up to descend on Puerto Rico for 10 intense days of morning-to-night workshops and charrettes focused on helping the island imagine rebuilding.

The Puerto Rico Re_Start group piled into school buses to tour sites devastated by the storm and then broke into five design labs, each with its own mission. The diverse, multidisciplinary group could have stopped there, handing off its ideas for rebuilding with resiliency and sustainability in mind to the Puerto Rican people, but the connections flourished.

The synergy created by their interdisciplinary work has turned research on Puerto Rico’s rebuilding into almost a full-time enterprise for Kohen, Clark and research associate Maria Estefania Barrios.

They’ve been to New York, back and forth to Puerto Rico, and presented at a conference hosted by FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Along the way, their network has grown.

In New York, at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College of the City University of New York, Kohen found herself talking with a cell service provider who wanted to establish direct satellite connections, not dependent on cell towers and Puerto Rico’s fragile utility grid. Earlier, she had been talking with an architect who told her he had identified 200 community centers that would be good sites for solar power. She made the introductions.

“I said, ‘Jonathan, do you know Jose Luis? No? Jose Luis, do you know Jonathan?’” Kohen recalled. “I got them together face to face, and now they are working together. Things can happen faster once these connections are made.”

A year after Maria, the UF architects have become glue people, playing a role in connecting NGOs and agencies, entrepreneurs and academics who want to help rebuild Puerto Rico.

“We need to connect information from churches, banks, authorities, all the people who want to do things but don’t know what everybody else is doing,” Kohen says.

Barrios has received special training to help with a Hunter College databank in its Center for Puerto Rican Studies to help with all the projects related to rebuilding Puerto Rico. Kohen notes that 990 NGOs, or nongovernmental organizations, work in Puerto Rico, but most are not connected with the others. With the databank, anyone can see who is doing what and team up. All the design labs for Puerto Rico Re_Start are on a website, which is linked to the databank, and they pop up with a keyword search.

And online is where FEMA found the UF team and drew them in to the government’s conversations about how to help in Puerto Rico’s recovery.

The architecture students’ instincts were right. UF could help, and in more ways than one.

Joining Forces

When Harold Lathon landed in Puerto Rico with a FEMA team to assess response and recovery options, he says he found storm damage of historic magnitude. That’s quite a statement, considering that Lathon cut his teeth on Hurricane Katrina, and he has seen the aftermath of catastrophic storms such as Hurricanes Sandy and Ike since.

He knew the response and recovery would require a huge team with diverse expertise, and he began to do some research. He came across Puerto Rico Re_Start and decided academia might have resources to offer. He reached out to Kohen.

“I was so impressed with her willingness to work collaboratively,” says Lathon, who is the transportation sector task force lead for National Disaster Recovery Support. “That’s the beauty of recovery, when you can find partners that are willing to work collaboratively. We will need additional strategic partners from academia, the public sector and the private sector.”

Lathon invited Clark to be a moderator of a panel on ecological urbanism and transportation recovery planning at a FEMA summit in July designed to bring together the best ideas for recovery.

In August, Kohen and Clark hosted Lathon on a visit to UF, and Lathon says he found on campus a wealth of resources that could be leveraged to help Puerto Rico rebuild.

“We have an opportunity to take a holistic, comprehensive look at reconstructing Puerto Rico, and we see a number of programs here at the University of Florida that could help,” Lathon says. “I’m excited to see the work going on in the various labs.”

In his three days on campus, Lathon toured the Powell Family Structures & Materials Laboratory, which researches hurricanes, earthquakes, and tornados among other structural stresses. He visited the GeoPlan Center, which uses geographic information systems to support planning for land use, transportation and the environment. He met with engineering Associate Professor David Prevatt, who studies mitigation of wind damage and the performance of residential structures under high winds. He also met with Morris Hylton III, director of UF’s Historic Preservation Program, and with Jeff Carney, the associate director for the Florida Institute for Built Environment Resilience.

The theme that runs through the UF labs and research programs is sustainability and resilience, and those two factors will be the key to both rebuilding Puerto Rico and girding the island against future hurricanes. In the midst of the challenge, he says, there are great opportunities.

“This is the first time in disaster recovery history that we find ourselves in a place where we may be able to provide a sustainable financial solution in recovery,” Lathon says.

Part of the challenge for Puerto Rico is its condition before Maria. The island never recovered from an economic downturn in 2006-08 and its infrastructure has suffered from decades of deferred maintenance. The power grid was already fragile before it was knocked out by Maria. That makes the Puerto Rico Re_Start approach – planning for sustainability and resilience – particularly attractive.

Now, with appropriations from Congress, roughly $50 billion, there is funding for the kind of planning that can rebuild Puerto Rico’s infrastructure and harden it against future hurricanes at the same time.

“We are looking to all hands on deck to support this effort,” Lathon says. “Fifty billion sounds like a lot, but it pales in comparison to a $300 billion problem.”

Perilous Position

Puerto Rico is accustomed to tropical storms and hurricanes, but the 2017 hurricane season was particularly vicious.

The eye of Hurricane Irma passed north of Puerto Rico on Sept. 6 as a category 5 storm, the strongest on record in the open Atlantic. Irma killed four people in Puerto Rico, cut power to two-thirds of utility customers and caused one-third of the population of 3.4 million people to lose access to clean water.

Reeling from Irma, the island was not ready for the hurricane warning

issued by the National Weather Service on Sept. 18, or the news that Maria had intensified more rapidly than any other hurricane ever measured. On Sept. 19, just hours before landfall, Reuters reported that 60,000 to 80,000 people who lost power during Irma were still without electricity.

On Sept. 20, Maria hit Puerto Rico with winds of 155 mph. Towns directly in the path reported 80 to 90 percent of structures destroyed and power was lost across the island, taking with it access to clean water. National Weather Service equipment on the island was destroyed and communications – internet, telephone lines and cellphone towers – were wiped out.

In the span of two weeks, the record set by Irma as the costliest Caribbean hurricane on record – at $64.8 billion – was eclipsed by Maria’s damage estimate, a whopping $91.6 billion. The death toll in Puerto Rico, first drastically undercounted at 64, is now estimated to be 2,975.

Other effects of the storm – defoliation of the island’s lush tropical landscape by extreme wind speeds – created a surreal atmosphere.

“Our island used to be green, be beautiful. Now it’s brown,” says Luis Rodriguez, a University of Puerto Rico (UPR) architecture graduate student who was hosted by UF after the storm. “It looks like a nuclear bomb left this. You wouldn’t think a hurricane could do that.”

UPR architecture Professor Anna Georas, who co-directed Puerto Rico Re_Start with Kohen and began her partnership with Kohen during her visit to UF after Maria, says she almost does not know how to describe the aftermath.

“People would be driving on the highway, and if they got a signal, they would stop the car and call their loved ones,” Georas says. “Our society shut down. We didn’t have food, we didn’t have gas, we didn’t have light, we didn’t have water.

“That’s so toxic for the younger people, so to get them to the University of Florida, where they could feel normal and productive, was very meaningful for them.”

For Georas and Rodriguez, another effect of the storm, the swelling of the diaspora, is disheartening although they understand the urge of their fellow citizens to seek a normalcy they cannot find on the island any longer. Even before Maria, more Puerto Ricans, roughly 6 million, lived outside the island than on the island, according to the Center for Puerto Rican Studies. After Maria, another 200,000 left for the mainland, many to Florida.

Georas noted that many professionals, particularly doctors and nurses, are leaving the island for the mainland, and Rodriguez laments the brain drain, but he understands it.

“I love my island. Every Puerto Rican will tell you, we love our island,” Rodriguez says. “But right now, if I want to have a minimal good life, I have to leave my island. It hurts, but it’s the truth.”

Designing Day and Night

Kohen, Georas and the design labs were on day seven of the Puerto Rico Re_Start workshop in March when they got a dose of what Puerto Ricans had been living with since Hurricane Maria. Power and internet connections went out at the host institution, the University of Puerto Rico Rio Piedras campus, bringing the design labs to an abrupt halt. As has been common in Puerto Rico since the hurricane, they found help from a neighbor: Polytechnic University of Puerto Rico. They packed up their suitcases full of drawing materials and decamped to the nearby school. Kohen wasn’t fazed.

“We are camping,” Kohen shrugged, as the design labs hummed all around her. “That is our situation right now, we are camping.”

The students banded together by design lab, with one in a stairwell, another gathered around a cluster of tables, another spread out on a landing, the architects and architecture professors moving among them. The students were oblivious to the conditions: working, chatting and munching snacks, focused on their work.

Leaving for dinner one evening, Kohen admonished them not to stay up all night, something architecture students are known for, but she acknowledged that her advice might not be heeded. The students were on a roll.

The problems they were trying to address – urban redevelopment, revisioning communities, making housing more resilient and less flood-prone, using natural systems to manage flood water – were a tall order for a 10-day workshop and they were determined to use every minute.

Some of the ideas, such as using shipping containers to meet a variety of needs in an emergency, were used by all the labs. Stephen Bender of CityLab Orlando, showed how the modest containers, generally 8 feet wide and 8.5 feet high, by either 20 or 40 feet long, could be transformed depending on needs: communications centers, sanitation stations, laundry facilities, camp showers, even impromptu dormitories.

In the mountain to coast design lab, led by Clark, the students addressed major flooding of communities along the Loíza River Basin that occurred during Hurricane Maria. For various at-risk towns, that lab proposed green infrastructure combined with new public amenities, using strategies designed to promote self-sufficiency and protect the vulnerable communities against future storms.

Another lab addressed the problem of abandoned buildings, partly due to the exodus of Puerto Ricans before the storm, but also after.

“People just lock their house and drive to the airport, park the car, leave the keys, take the plane and say good-bye,” Kohen says. “We saw abandoned cars, abandoned buildings, and there is not a policy for how to reuse the buildings.”

Georas notes that 44,000 buildings may be abandoned, and some could be reconfigured as housing units, potentially repopulating the urban core.

“Redensify and fortify, abandon certain areas back to nature. Reconcentrate. Become stronger and safer. It may be safer to huddle together as these storms become stronger.

“Puerto Rico needs a paradigm shift from typical urban plans. We can draw beautiful walkways and parks. That’s a wonderful way to approach urbanism, under the presumption you’re always going to have citizens,” Georas says. “But we’re emptying, so who are we going to make the park for?”

Rebuilding with Resilience

Lucio Barbera, the chair for sustainable urban quality and urban culture for UNESCO – the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, led one design lab and offered comments as the students presented their ideas during their final day on the island. The jury had pelted the students with questions, and the students had to defend their work. Barbera, an architect himself, asked them not to be discouraged.

“Design is an interdisciplinary activity,” Barbera said. “It is the typical duty of we architects to synthesize and present the first ideas that must be understood by everybody. I hope these young architects, who worked so hard, are not discouraged.”

The mission of Clark’s design lab grew this fall, as she co-teaches a graduate seminar called Scaling Landscapes with Kohen. Her design lab in March took a holistic approach to address water management from the mountain town of Cubuy to the coastal town of Loiza, and in Scaling Landscapes, students are taking a comprehensive look at the La Plata River Basin.

“Instead of a 10-day charrette, we are using a 16-week effort to look at the entire river basin and come up with a master plan that could serve as a model for all the other river basins on the island,” Clark says.

When the class visited Puerto Rico in the fall, it exchanged ideas with students and professors from PennDesign, the University of Pennsylvania School of Design, and Georas’ students from UPR, who are working with other river basins.

The idea of green infrastructure, using natural resources to channel water as opposed to building dams, is gaining momentum, Clark says, and that large-scale, sustainable infrastructure approach is important to the Center for Hydro-generated Urbanism, which she and Kohen direct. The big picture approach is also something Puerto Rican officials seem to be ready to embrace.

“I’m really optimistic because there is an understanding that something different has to take place,” Clark says. “There has been a shift in attitude about what the future can be for Puerto Rico. They don’t want to just build back the same way. Puerto Rico can become the model for other vulnerable, at-risk places.”

Barbera, of UNESCO, agreed.

“Puerto Rico is like a laboratory of things that happen other places on the planet,” Barbera said in March. “Looking into this, we are learning for a much wider audience than Puerto Rico.”

Rodriguez, who floated between all the labs in March, answering questions about Puerto Rican culture and customs to help the labs develop ideas with real-world applications, said he hopes the labs’ ideas are followed up.

“I hope our politicians realize we need these projects,” Rodriguez said. “I hope these projects are not placed in a box in a corner of an office.”

For her part, Kohen would not let that happen. She is getting ready for her third trip to Puerto Rico in less than a year this fall, and the second Puerto Rico Re_Start workshop is already on the calendar for March 21-30. The workshop will grow, and FEMA will participate this time.

UF may be a plane ride away, but Kohen says it is positioned to do research and offer assistance, even for the next 10 or 20 years; however long it takes to restart Puerto Rico.

“At UF, we know tropical communities, we know climate, we know immigration and Hispanic traditions, we have established hurricane research and much more that could be put to good use in rebuilding,” Kohen says. “We have a long history of Puerto Rican culture in Florida.”

Sources:

- Martha Kohen, Professor of Architecture

- Nancy Clark, Associate Professor of Architecture

Related Websites:

Photo Illustration By: K Kinsley-Momberger

Additional UF supporters of work in Puerto Rico include the Center for Latin American Studies, the International Center, the Shimberg Center for Housing Studies, the Center for Hydro-generated Urbanism and the Office of Research.

This article was originally featured in the Fall 2018 issue of Explore Magazine.