At least a month before Florida recorded its first case of COVID-19, the University of Florida’s Emerging Pathogens Institute had a diagnostic test ready for research purposes. This was not a random one-off slam dunk; it was by design, one of the institute’s many dividends from investing 14 years into pathogens research.

Since the institute’s inception, EPI Director J. Glenn Morris Jr. has held an enduring vision to foster interdisciplinary research teams that span UF’s campus — and the globe — to tackle investigations of pathogens that infect people, animals and plants.

The goal? To understand all aspects of how pathogens function and spread. In this sense, the EPI has served as an incubator for pathogens-focused research from basic to translational science.

“The more we know about pathogens, the more prepared we can be for new outbreaks,” Morris says. “The whole point of our institute is that we can follow trails that go in various directions and do more than a single investigator could alone. It’s all about the collaboration, the networks, the ability to take parts from different things and bring them together, and to focus rapidly on key scientific questions and concerns.”

The EPI was conceived in a post-9/11 world where weaponized biological agents weighed heavily on the minds of defense experts and politicians. But EPI’s creators thought bigger and established its scope to include all pathogens. This wide-angle view is what helped position the EPI to respond with speed to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Over time, the EPI has created an interdisciplinary setting where we bring together top scientists who are looking at the reasons for why these novel microorganisms emerge, how they transmit between hosts, and how they cause infection and disease, or can be detected,” Morris says. “By creating these teams in advance, we were prepared in this case, and we were ready at the gate to begin doing high-quality science.”

Ready, Set, Test

In January, when scientists first identified the novel coronavirus as SARS-CoV-2 and surmised that it had likely spilled over into people from bats, Morris conferred with John Lednicky, a virologist with expertise in coronaviruses. The pair had previously sampled bats in Florida for coronaviruses, and Lednicky had developed — then set aside — an assay that detected betacoronaviruses, the virus subgroup that included the novel coronavirus at the center of COVID-19.

If the virus came to Florida, Morris wanted to ensure that the EPI had the ability to test people for research purposes. Their planning proved prescient.

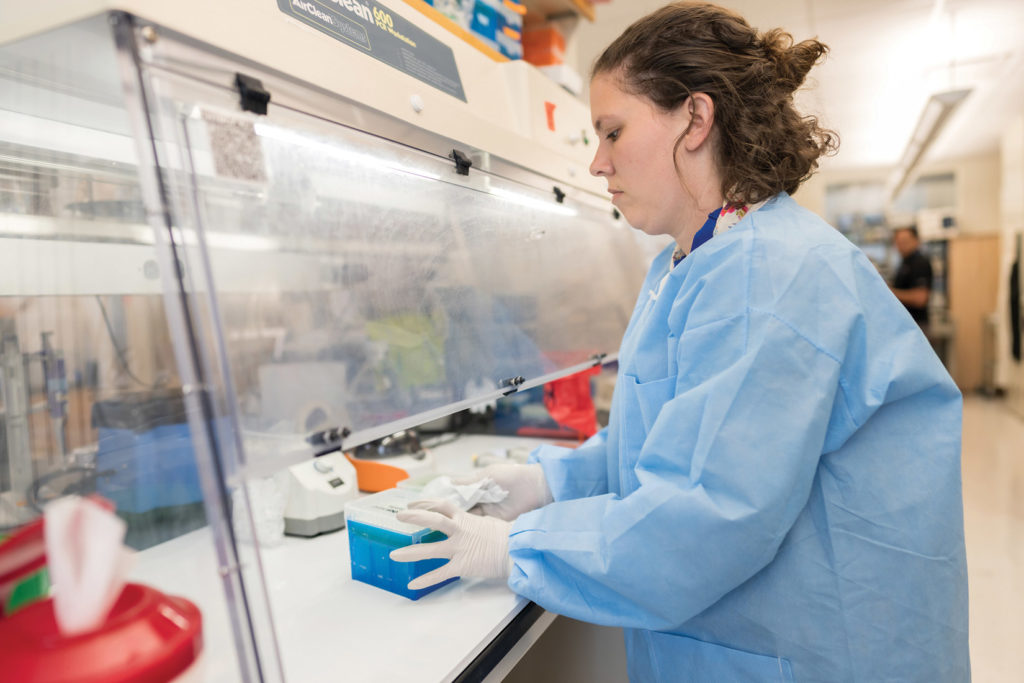

When Florida cases began to mount in mid-March, the institute rapidly converted one of the laboratories in its 93,000-square-foot, high-containment facility to process up to 1,300 COVID-19 tests per week. By fall, capacity had increased to 1,700 tests weekly.

The testing was part of seven community surveillance projects that aimed to monitor high-risk populations. Key researchers from the Department of Environmental and Global Health in the College of Public Health and Health Professions and the College of Medicine said that the 10-day buildout would have taken at least a month under normal circumstances.

And to protect its students and employees, EPI supported UF Health in its development of a campuswide protocol to “Screen, Test & Protect,” which relied in part on tracing the contacts of people who test positive for COVID-19. EPI helped by converting its large conference rooms — largely unused due to the pandemic — into socially distanced hubs for contact tracers.

“Within the sphere of the university, the Screen, Test & Protect program has worked very well to limit the spread of COVID-19 at UF,” Morris says. The program is overseen by EPI’s deputy director, Dr. Michael Lauzardo, who is also an associate professor of infectious diseases and global medicine.

Protecting Communities

With the high-capacity laboratory in place, EPI helped spearhead or support seven different testing studies for high-risk populations. The first and most visible program took place at The Villages, a massive retirement community in Sumter County, where symptomatic individuals could receive an FDA-approved COVID-19 test, and asymptomatic persons could be screened as part of EPI’s research activities.

Next, the EPI helped College of Medicine researcher Lisa Merck with a study that offered testing to city employees and emergency responders in Gainesville. Other community testing studies included farmworkers in Orange County, aquaculture workers and community members in Cedar Key, people within vulnerable neighborhoods in Jacksonville, school-aged children at P.K. Yonge Developmental Research School in Gainesville, and the homeless at Grace Marketplace, also in Gainesville.

At the pandemic’s onset, most of the surveillance studies used nasal swab testing to detect active infections. But over time, the studies added in serological testing to detect immune responses from past infections. The school-aged study also included a social science component designed to assess the pandemic’s effect upon the incidence of depression, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder. At the broadest level, the goal of these studies was to test healthy individuals to better understand the role played by people with symptomless infections in spreading the virus, and the degree of vulnerability of frontline personnel.

These community studies were created and executed by interdisciplinary teams, with EPI’s support, that included volunteer medical students, public health researchers, microbiologists, medical researchers, a law professor and an environmental toxicologist.

Molecular Targets

Researchers affiliated with the EPI are also hunting for molecular targets that could aid in developing drugs for COVID-19 treatments. A team with EPI members is harnessing the power of genomic editing to illuminate drug targets in human cells for the fight against COVID-19.

By taking advantage of the institute’s high-containment labs, the team is using CRISPR genome editing techniques to screen human cell lines. Their goal is to discover genetic factors that either hasten or thwart infection by SARS-CoV-2.

The team includes Christopher Vulpe, a professor in UF’s College of Veterinary Medicine, in collaboration with Stephanie Karst, a professor in the College of Medicine, and Mike Norris, a professor in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. Karst and Norris are EPI faculty.

Karst was already working on a project funded by the National Institutes of Health to identify host factors for other viruses when she contacted Morris about working on COVID-19 research. Morris connected Karst and Vulpe, and also suggested they work with Norris, who has an extensive background working in biosafety level III and high-containment labs.

They join researchers across the nation who seek a deeper understanding of how the SARS-CoV-2 virus causes disease and severe symptoms, knowledge that will help design therapeutic drugs.

Modeling Better Outcomes

The EPI also supports researchers who use mathematical and statistical tools to create models of how infectious diseases are transmitted or move through a population. Models can be powerful tools for estimating how strategic interventions — such as public health strategies, vaccines or therapeutic drugs — can help achieve better outcomes in a disease outbreak.

One such researcher is Ira Longini, a professor of biostatistics in the College of Public Health and Health Professions. An EPI faculty member, he serves as an adviser to both the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization, where he was a key member of the team developing an Ebola vaccine.

Longini contributes to the design of clinical and vaccine trials to ensure they are robust enough to deliver an optimal product that is both safe and effective. This year, he’s been busy contributing to models of the pandemic’s trajectory in the US with collaborators at the GLobal Epidemic And Mobility project (gleamproject.org). GLEAM models have accurately projected deaths from COVID-19 nationally several weeks in advance.

Longini and colleague Natalie Dean, also a member of the EPI and the biostatistics department, recently collaborated with Northeastern University’s Laboratory for the Modeling of Biological and Socio-technical Systems. The team analyzed what would happen if countries either “cooperated” or were “selfish” when distributing 3 billion doses of a hypothetical COVID-19 vaccine across the world. Their work shows that when nations cooperate on vaccine distribution, they can save far more lives globally than if wealthy nations focus only on their own citizens. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation featured this model in its 2020 Goalkeepers Report.

Thomas Hladish, in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, worked with Longini in the spring and summer to produce models published on EPI’s website that projected the pandemic’s trajectory in Florida. And Burton Singer, a mathematician in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, collaborated with researchers from the Yale School of Public Health to project hospital and intensive care unit capacity in the U.S. His most recent work, under peer review, analyzes optimal strategies for testing and quarantine strategies to bring the pandemic under control.

What’s Next?

Once the current pandemic is controlled, Morris plans to continue his approach of investing in interdisciplinary teams to prepare for the next novel infectious disease.

A pandemic flu is a perennial threat on many people’s radars due to its fearsome transmission levels, but the next one could also be a lesser-known filovirus akin to Ebola, a new mosquito-transmitted virus, or even a highly transmissible but drug-resistant bacteria. Though he can’t shake a crystal ball and predict the future, Morris’ approach at the EPI has shown the inherent value of investing in a broad and interdisciplinary research agenda over time.

“This is what we are here for,” Morris says. “Investigating what makes pathogens tick is what our people do best.”

Source:

J. Glenn Morris Jr., Director, Emerging Pathogens Institute

Related website: