On Friday afternoons, Keith and Stephanie Early load up their service dog, Riley, and drive to Gainesville to fill a prescription. Instead of heading to the pharmacy, the Earlys arrive at an industrial park on the outskirts of town where they’ll spend the next few hours blacksmithing at Crooked Path Forge.

“It redirects your train of thought. It keeps your mind off stuff,” says Keith, who has post-traumatic stress disorder.

He pulls a glowing metal rod from the 2,600-degree forge, places it on an anvil and starts shaping it with a hammer. After 24 years in the Navy and Air Force, he’s used to staying calm in dangerous situations. Blacksmithing, though, is helping Keith and his wife, a fellow veteran, find that calm throughout their lives.

They’re part of a University of Florida program in social prescribing, connecting patients to arts and cultural activities as part of their healing.

The pilot, launched by UF’s Center for Arts in Medicine and the Veterans Administration, is one way researchers are laying the groundwork for social prescribing nationwide, and not just for veterans. As overburdened primary care providers struggle to meet patients’ needs, community activities like these show promise to boost wellbeing and prevent the onset of disease, says the center’s research director, Jill Sonke, a research associate professor in UF’s College of the Arts.

After a few months of filling their social prescriptions at the forge, the Earlys are believers.

“It keeps me from the places I don’t want to go in my head,” Stephanie says. “When I feel that’s about to happen, I can start thinking about projects I’m working on. That can completely take it away.”

A National Model

In the United States, you won’t find many doctors sending patients to choir practice or insurance companies covering painting class. But in the United Kingdom, the National Health Service’s Arts on Prescription connects patients to cultural activities that match their interests — and funds their participation. Researchers there have linked community arts and cultural engagement with better mental health and overall wellbeing, lower risk of depression, and fewer childhood adjustment problems. That led UF’s EpiArts Lab, a National Endowment for the Arts Research Lab, to look for similar correlations in the U.S.

Their findings so far are promising — but the vast differences between the health care landscapes of the two countries pose some significant challenges. While the concept is in use in places from Japan to New Zealand, widespread social prescribing has thus far been limited to nations with some level of socialized medicine, Sonke explains.

“We’re one of the first third-party payer nations to explore it, so we need to develop viable, sustainable financial models,” she says.

That requires collaboration across the health care, insurance, public health and arts sectors at the local and state level. Proponents of social prescribing need to show not just economic benefit through reduced burden on providers, but evidence that Americans will accept it.

“Our health care system doesn’t have a structure that enables people to engage in things that are enjoyable and support their health. We’re acculturated toward taking medicine,” Sonke says. “If your doctor says, ‘I think you need to take a pottery class or a dance class, to get out and be more social and more creative,’ is that going to feel like you’re not being taken seriously?”

Even the name presents an issue.

“Social prescribing as a term works in the U.K., because social care is a concept that everyone understands. In the U.S., social services are highly stigmatized and highly politicized, so that language is problematic,” Sonke says.

They’ll also have to factor in some communities’ differing levels of access to both health care and the arts to ensure that social prescribing doesn’t deepen those inequities. The challenges are daunting, but with more than 30 years of expertise in the field, UF researchers are uniquely placed to take on the challenge, says College of the Arts Dean Onye Ozuzu.

UF Health Shands Arts in Medicine began in 1990, leading to the nation’s first university-level Arts in Medicine curriculum in 1996 and the founding of the Center for Arts in Medicine three years later.

“We’re at a moment in the evolution of this work where it’s time for people who understand its value to collect around it,” Ozuzu says. “It’s wonderful to see our center as the hub of this

electrifying conversation.”

Social prescribing differs from arts in medicine in a few key ways. Instead of bringing arts into a health care setting, it aims to infuse social and cultural activities into daily life. Second, the activities are led by artists and community-based organizations, not health care workers or therapists. Third, while clinical treatments are intended to serve their purpose, then end, social and creative arts involvement can continue after medical intervention concludes.

When a health care provider identifies a patient who could benefit from social and cultural engagement, they refer them to a “link worker” whose role is to match them with an activity in their community, Sonke explains. And while it’s not meant to replace medical intervention, it gives primary-care providers more ways to help patients who aren’t thriving.

“So many doctors relay the frustration of not being able to offer these patients what they need in a 15-minute visit. If we can broaden their toolkit, we can help alleviate the burnout and anxiety that comes from those limitations, and connect people to resources in their own communities that can address those needs.”

To show insurers, health care providers and patients that these programs work — and make sure they’re implemented effectively — Sonke and a network of researchers and advocates have begun studies with 23 pilot programs to explore the feasibility of social prescribing in the U.S.

The center’s work garnered $300,000 in support from the Pabst Steinmetz Foundation in 2022, plus $200,000 each from National Endowment for the Arts and Bloomberg Philanthropies. With the World Health Organization on board as a collaborator, the center gathered like-minded groups in Orlando in October, where they envisioned a prescription for healthier living through the arts.

Creating Healthy Communities

Filing back into the Creating Healthy Communities Convening, participants had the subdued demeanor of a post-lunch conference crowd assembling for the second half of the day’s agenda.

Then Alana Jackson took the stage.

A spoken word artist, researcher and lecturer at UF’s Center for Arts in Medicine, Jackson unleashed a call to action in the form of a poem titled “The Proposal.”

Excerpt from The Proposal

…what if when Grandma went to the doctor

she was given even more than just another pill and another bill

what if as part of her prescription she was pointed to a community of movers and shakers that shared her childhood love of dance

reconnecting her with the musical sounds of her heyday showing her that hey —

her condition was no obstacle to her capacity…

what I’m saying is, people need healing and policies need changing, but

WE can’t do that without YOU.

we need the power of your languages to rewrite our policy to the music

of transition and keep tempo

with the art that lives in each of us which means WE need YOU in order to

remember that sometimes

feeling pulled in two different directions like medicine or music,

stability or art,

is actually the key to our equilibrium, once we allow them to coexist

art and health are not mutually exclusive.

Throughout the two-day gathering, 450 attendees grappled with the opportunities and challenges of infusing the arts in public health. In his keynote speech, WHO Arts + Health Lead Christopher Bailey explained that arts in health doesn’t mean ‘if we sing this song, it cures that condition.’”

“I would like to disabuse us of that notion up front,” he said. “There’s a difference between curing something and healing something. The arts are about healing.”

The WHO’s definition of health “is not merely the absence of disease,” he explained, while its definition of mental health “is not merely absence of mental illness, but the ability to cope with the everyday stresses of life.”

Those stresses that might bring patients to their primary care provider looking for a medical intervention when a community or cultural intervention might work as well — or better, Sonke says.

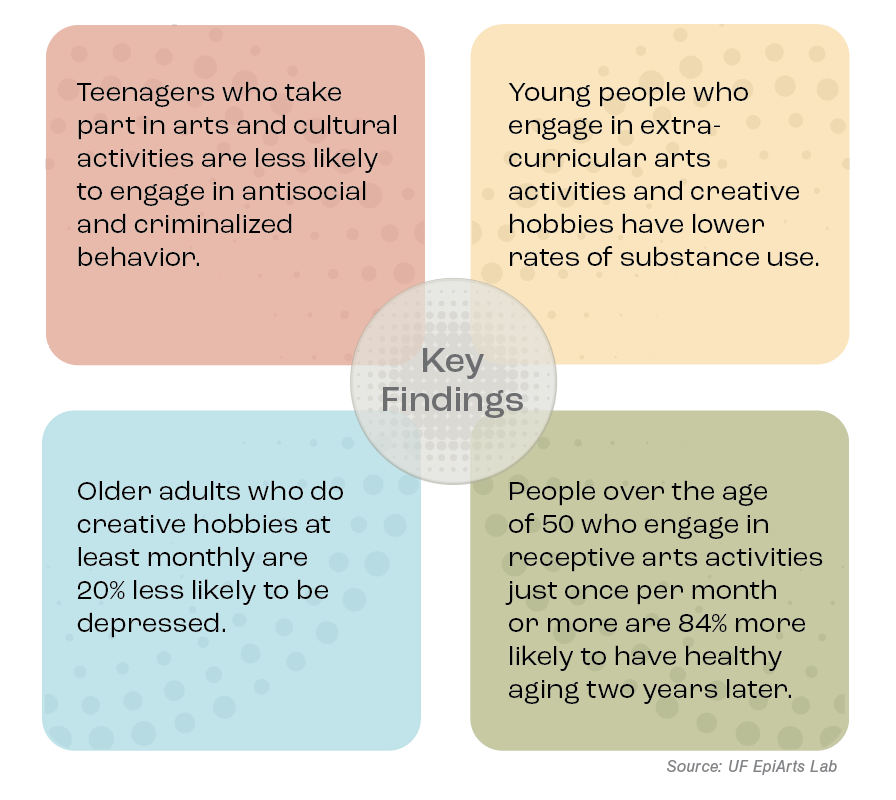

Studies from the United Kingdom and EpiArts Lab revealed improvements in depressive symptoms, cognition and memory, and overall well-being in older adults. Among adolescents, participation in arts and cultural activities was shown to reduce loneliness, risk of substance use, behavior and attention problems, as well as result in fewer reportedly anti-social or criminalized behaviors and improved self-control. In the U.S, Sonke and collaborators draw on seven data sets to evaluate those connections. So far, the results are encouraging: A forthcoming study of 1,269 older adults showed that, after adjusting for demographic and socioeconomic variation, engaging in arts activities once a month or more was associated with 84% higher odds of healthy aging two years later. (It’s worth noting that the arts activities weren’t even hands-on, but what researchers call receptive activities, like going to a concert.)

“That means engagement in the arts could have a greater protective effect than exercise, in less time,” Sonke says.

Ozuzu hopes findings like these will underscore the value arts deliver for health, not only for the benefit of patients, but the aspiring artists in her college.

“As artists, we’ve always known that art builds your health, but having it demonstrated in a large cohort in such an undeniable way — that really got me excited,” she says. “It’s good news for American society in general, and for our graduates’ ability to build middle-class lives with homes and health insurance, making a solid living as artists.”

Forging Connections

Back at the forge, Keith Early puts the finishing touches on a striker for a dinner bell, while Stephenie shapes a lantern hook for their yard.

“This has been so great for the both of us,” Keith says. “I wish it could go on forever.”

While the pilot program — an outgrowth of decades of partnership between UF and the VA — has concluded, the lessons learned will continue to shape the VA’s approach, says Dr. Chuck Levy, research physician for the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine.

Levy, who pioneered art therapy via teleheath as chief of the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Service at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System, wants to see success stories like the Earlys’ continue.

“I believe it’s highly likely that our work here will lead to wider scale adoption of this practice,” Levy says.

“Part of our mission is to change how people perceive the realm of health care. We didn’t always believe that diet and exercise were important, or that a physician should ask about those things and advocate for that. The next step may be for physicians to say, ‘What are you doing for creative expression? How are you engaging in aesthetic experiences to enrich your life? And if you don’t have anything going on, maybe that’s something we should discuss.”

Along with its successes, including building a referral process and training materials for the arts organizations, the pilot revealed some limitations, including the difficulty in reaching rural areas far from the participating arts organizations — one reason for its modest sample size of 18 veterans. That echoes concerns emerging from a recent workshop for policy makers, insurance providers, artists and other stakeholders, including Sonke, at Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

“Social prescribing needs to be accessible for people who aren’t insured or well insured and don’t have access to preventive care,” she says.

“The big picture goal here is that Americans understand that, like exercise and good nutrition and wearing seatbelts, being creative and engaging in cultural activities is a resource that we have available to us for our health.”

The idea is gaining momentum: One of the nation’s largest metropolitan areas is consulting with Sonke on how to implement social prescribing for its residents.

“They want to do it fast, and they want to do it big,” she says.

The momentum reflects a dawning appreciation in the U.S. that the arts are more than a luxury, Ozuzu says.

“Artists have always been agents of the kind of collective change we need today,” she says. “This is our moment.”

Source:

Jill Sonke

Research Director, Research Associate Professor, Center for Arts in Medicine

jsonke@ufl.edu

Time in Nature May Spur Healthier Choices

Social prescribing extends beyond the arts. A growing body of evidence shows that exposure to nature could help stem drug cravings, says Meredith Berry, an experimental psychologist in UF’s College of Health and Human Performance.

In graduate school, Berry was gathering visitor perception data in Yellowstone National Park when she noticed that “people would share their stories of healing in nature,” she recalls. She’d had similar experiences, and started wondering about the science behind such claims.

As an addiction researcher, she hoped that healing could be brought into play for substance use or misuse. In a recently published study, Berry and doctoral student Shahar Almog found that active exposure to nature has protective effects against harmful alcohol use. In other studies, just looking at nature photos reduced impulsive decision-making.

“That kind of decision-making is correlated with a lot of health behaviors like smoking, alcohol use, diet, even gambling,” she says. “There’s some evidence that we can nudge people towards healthier choices.”

In a forthcoming study, people who use drugs looked at a photo of a natural area or a built environment, then reported what quantity of drugs they would buy at various price points, which researchers use to quantify the subject’s motivation to take the drug.

“What we’re seeing is, people report hypothetically buying less of the substance when they’re exposed to nature versus when they’re exposed to built environments,” Berry says.

A new pilot study extends the work to opioid users with chronic pain, which is twice as prevalent among people with opioid use disorder than the general population. She hopes nature exposure can be a complement to counseling and medication.

“We’re always trying to move the needle, because treatment for things like opioid use disorder, it’s just tricky. Some people respond to pharmacotherapy like methadone or buprenorphine, and others just don’t and we don’t know why,” she says.

Berry sees potential for nature prescriptions to ease the depression and anxiety that often accompany pain and substance use.

“Any of these factors could be helped by nature exposure, but almost none of them have been tested in these populations,” she says. “We need to test these innovative approaches that are all around us.”

Source:

Meredith Berry

Assistant Professor of Health Education and Behavior

mberry@ufl.edu