Sea level has risen about 8 inches in the last century, and heat records have been broken, only to be broken again, and again.

In human time, this is new, but the Earth has been here before, bathed in a warming atmosphere, and has left clues for scientists like University of Florida geochemist Andrea Dutton. In the rocks is a geologic archive, the history of rising seas, and by following the clues, Dutton hopes to inform the future.

One archive is the Seychelles, the planet’s oldest ocean islands along the equator in the Indian Ocean. In 2013, Dutton was examining the islands’ fossilized corals, some as much as 129,000 years old, when she got a jolt.

“I found a fossilized coral that was 8 meters above present sea level,” Dutton says. “I literally sat down in the field. That’s really high, it’s 26 feet. I thought, ‘People are not going to like this.’”

Her next thought: “How am I going to explain this?”

Current sea level rise is due to thermal expansion of seawater as it heats up and melting of mountain glaciers, and the scientific consensus was that, at current warming trends, sea level would rise 3 to 6 feet by 2100. That estimate includes only a minor contribution from Antarctic ice melt. The only way to explain a water volume that would have submerged the fossilized corals she found, Dutton realized, was ice melt on a massive scale.

Dutton uses temperature to find analogs in the past for today’s heat, although the heat of the past occurred without the contributions of 7.6 billion humans. The fossil coral held an ominous message because the coral was found in rock from a period 116,000 to 129,000 years ago known as Marine Isotope Stage 5e, only one degree Celsius warmer than pre-industrial levels.

“People had debated whether the West Antarctic ice sheet collapsed during this time period, and this was one of our first indications that it did,” Dutton says. “That was a real eye-opener.”

At a temperature roughly as hot as it is today, the Seychelles was under more than 20 feet of water.

At that level, South Florida, the Florida Keys and the Everglades disappear.

Water, Water Everywhere

Sea level rise is like a flood that never recedes. Think of photos of Hurricane Katrina’s aftermath in 2005 — the costliest flood in U.S. history — and imagine if New Orleans still looked like that today.

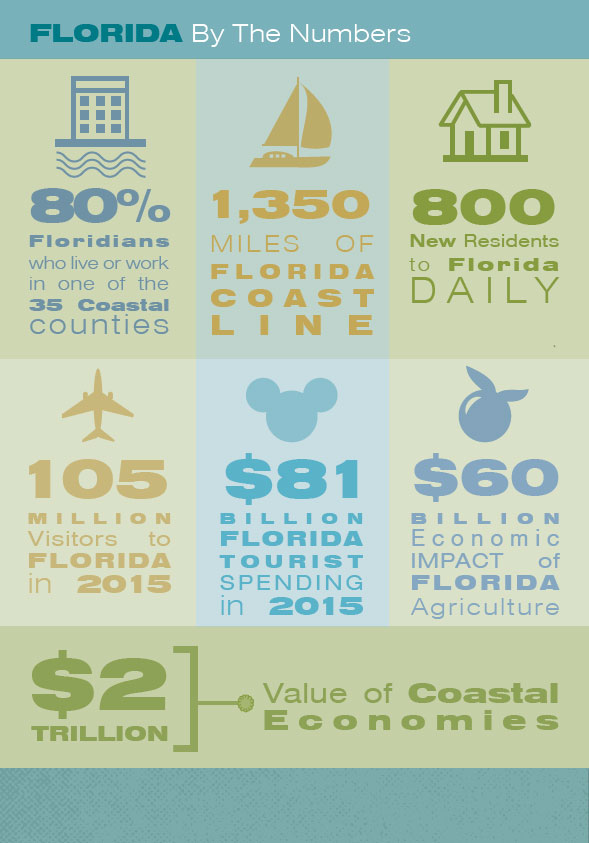

Now, take a look up and down the coast of Florida, the state with the most people and the most property vulnerable to sea level rise. About 80 percent of the state population lives on a coast, coastal economies are worth $2 trillion, and the coast is not only low but flat, meaning a little bit of sea level rise goes a long way inland. The inland flow of seawater would soak the limestone sponge that holds about 90 percent of Florida’s drinking water, contaminating it.

If Florida is vulnerable, Miami is ground zero, and Thomas Ruppert, a Florida Sea Grant coastal hazard specialist based in Miami, spends his days trying to help local governments address rising seas, doing presentations to share his research and writing.

“My job is to inform and to get them to think about these issues,” Ruppert says. “In Miami, you can’t talk polar bears. But if you can get local government managers to talk about money, talk about legal liability, that gets their attention. This is going to be expensive.

“From a citizen’s perspective, who do you think is going to pay?” Ruppert asks. “If the local government is paying, that’s you. This is going to cost you a lot of money.”

Ruppert came to Sea Grant in 2010, when it advertised for an attorney with expertise in coastal planning and zoning.

Ruppert had been working with UF’s Levin College of Law in its Conservation Clinic, and was well-versed in coastal issues. His legal background is increasingly valuable.

One question he often gets after a public talk is what a citizen can demand of his local government. What is the local government required to do to help him cope with rising water? The answer, quite often, is nothing. Local governments are long on authority to do a variety of things, but are not required to do those things.

“People assume government has to help them,” Ruppert says, “and it’s not always true.”

Take drainage, for example. Local governments do not have to provide drainage. If they do, they are required to maintain what they build, but not required to expand it.

Still, a local government with deep pockets and high-value real estate might decide to improve drainage, and a case in point is Miami Beach, which is spending $400 million to $500 million on pumps after grappling with periodic “sunny day” flooding from extreme high tides. The tide gauge on nearby Virginia Key has registered a 2.5- to 3-inch increase in sea level in just the past 16 years, and that makes drainage, designed to use gravity to take water downhill, an issue. Water, after all, won’t flow up. The pumps, 60 are planned, will suck water from the streets and toss it back into the Atlantic Ocean or Biscayne Bay.

Miami Beach is also repaving to raise the level of streets. A Publix that once had seven steps at its entrance, now has two, thanks to higher streets. An almost 100 percent increase in stormwater fees is financing the changes, Ruppert says, and in coming decades drainage will be a multimillion-dollar question for other communities as well.

“If you require local governments to provide drainage in the future that provides the same service as in the past,” Ruppert says, “you’d bankrupt some of them.”

Drainage and pumps are extremely expensive, and that brings up the societal cost of sea level rise, Ruppert says. The more communities invest in drainage, the less they can invest in education, roads, parks, community centers, the things that make a place worth living in. What happens to communities without Miami Beach’s deep pockets?

“In Florida, we’re just really unwilling to stop and look at this,” Ruppert says. “In a way, the emperor is wearing no clothes in regard to what we’re doing on our coastlines.”

Starting a Conversation

Researcher Kathryn Frank has met that metaphorical emperor in her work to help communities plan for rising seas. When she started working in Northeast Florida in 2011, the steering committee for the project shunned the term “sea level rise.” Then Hurricane Sandy swept up the East Coast in 2012, taking chunks of Northeast Florida beaches with it. On Sandy’s heels, a smaller storm that would have been unremarkable even a few years ago eroded the shore even more.

“They decided to just call it sea level rise, and it was fine,” says Frank, an assistant professor in the College of Design, Construction and Planning. “They were ready to start the conversation.”

Frank works at the community and regional scale to help communities assess their vulnerability to rising seas and then look for adaptation strategies for economics, safety, natural resources, and heritage.

“They care about all those things, and they want to keep all of them,” Frank says.

At UF’s GeoPlan Center, Associate Director Crystal Goodison has noticed smaller communities getting started without waiting for someone to tell them to plan. Regional transportation agencies, in particular, are clamoring for information.

Goodison points them to resources on the GeoPlan website: a map viewer that shows sea level rise over time, a wealth of data, and geographic information systems (GIS) software that allows users to create their own sea level rise scenarios using their own data.

The tools were developed for the Florida Department of Transportation, but are open to anyone. GeoPlan developed an interactive map that allows sea level to be mapped at high, medium and low levels every 20 years from 2020 to 2100, and it allows FDOT to overlay locations of railroads, highways and bridges in making decisions about hugely expensive infrastructure built to last many decades, even into the next century.

“Think how important transportation is in our economy,” Goodison says. “If roads come to a standstill, we’re not moving people to work, we’re not moving freight, we’re not moving tourists.”

Goodison and Frank say it’s heartening to see communities begin to plan, some using new state laws that allow towns to consider adaptation to sea level rise in their comprehensive plans.

Part of building resilience is helping citizens come to grips with uncertainty, Frank says. When will sea level rise, by how much? No one knows. But Floridians don’t know when the next hurricane will hit or how strong it will be, and they prepare nevertheless.

“There is so much uncertainty,” Frank says. “How do you internalize that way of thinking about the future?”

Frank has worked in the Matanzas Basin on the Atlantic Coast and on the Gulf Coast in Cedar Key, where change washes in on the tide. The town turned to clam farming when its commercial fishing economy was devastated by a state net ban. More recently, its oyster industry collapsed. Cedar Key has been resilient; life has gone on.

Today, Frank talks to Cedar Key and other communities about life-spans. Just as people and pets, houses and cars, have lifespans, so do communities. Mitigation and adaptation help, depending on how the seas rise.

“We accept lifespans in other areas of our lives,” Frank says. “There is a different lifespan going on here. Some things we can move, other things we can enjoy while they’re here. Sea level is going to keep rising; some places are going to be under water. It’s just a matter of when.”

Awareness of sea level rise varies widely, Frank says. Recently, she spoke at Flagler College, which started out in 1888 as the Hotel Ponce de Leon, built by railroad tycoon Henry Flagler. The college is in St. Augustine, which just celebrated its 450th anniversary. A student came up to her afterward.

“He was almost in tears. He got it, cognitively and emotionally,” Frank says. “When people get it, it’s like an a-ha moment.”

Money, Money Everywhere

In South Florida, where residents witness sea level rise, Ruppert has different conversations. During the last king tide, in October, Ruppert pulled on rubber boots and went to survey the flooding. On a postcard-perfect day, boats were floating at seawall level, cars were marooned, water was gushing up out of storm drains. Along one canal, portable barriers were duct taped together in an effort to keep the canal out of the street. In front of one swamped home, the homeowner ran up to him with a question.

“He wanted to know, ‘What are they going to do about this?’ Who is they?” Ruppert asks.

For now, pumps and higher streets are the government response. Some residents are elevating homes and building seawalls and crossing their fingers. But seawalls, built on the porous limestone that is Florida’s foundation, don’t work; water comes up under them. And once your home is elevated, how do you get to it? Seawalls and stilts won’t necessarily save the coast.

“One neighbor without a seawall can flood the entire neighborhood,” Ruppert says. “Any action at the parcel level is flood mitigation, not adaptation. Adaptation takes collective action at a community or regional level. The approach has to be systemic.”

In Miami, in the midst of the South Florida economic engine that funds one third of the state budget, there are resources for sea level rise.

At least 30 high-rises are under construction in downtown Miami. But the expense of coping with rising seas is not a burden everyone can bear equally, Ruppert says. Even on Miami Beach, the U.S. Census Bureau estimates 17.5 percent of the population lives below the poverty line. The middle class will be affected when sea level rise affects the ability to insure a home, or sell it.

“Something positive can come out of this if we can actually start a real conversation about public policy, property, the government’s role,” Ruppert says. “It’s an insurance issue, it’s a banking issue, it’s a local government tax base issue.”

Ruppert wonders if a bill is coming due for past coastal real estate booms. So many beach towns, he says, may be a beach in name only in the next century.

“Our barrier islands are a few hundred feet wide in some places. There’s no way that’s a smart place to build, but there was always so much money to be made,” Ruppert says. “We need to realize our actions today set a course for the future.”

People ask how to fix the problem, they want solutions. There is no solution, Ruppert says, for the Atlantic Ocean. Sea level rise is like growing old; we know the ending. But people can choose to age gracefully, and Ruppert says communities can choose to adapt gracefully, too. Doing so will just require a much greater level of planning.

High Tide

Florida has been here before, swallowed by a rising sea, and has left evidence behind for archaeologists like Paulette McFadden at the Florida Museum of Natural History. Examining sediment cores in Horseshoe Beach along Florida’s Gulf Coast, she found clues to how pre-Columbian inhabitants as far back as 4,000 years ago adapted to sea level rise.

“These people likely had generations of knowledge of sea level rising, so it was ingrained in their culture, the expectation they would have to move. It doesn’t mean that places didn’t have meaning, that it wasn’t sad to lose them, but they had an experience of living on a coast that was changeable,” McFadden says. “They didn’t have a multimillion-dollar skyscraper sitting on the beach.”

McFadden also found evidence in the sediment cores of variability in the rate of sea level rise. In some cases, sea level rose slowly, and the marshes stabilized as they took on more water. In others, sea level appears to have been more sudden.

“We see these punctuated events in these cores, and they correlate closely with the dates of changing settlement patterns,” McFadden says. “These populations were much more vulnerable to a large pulse in sea level rise.”

That pulse is what Dutton and other geologists want to quantify. Polar ice melting little by little is bad enough. The collapse of a sector of the Antarctic ice sheet into the ocean is another thing entirely.

The West Antarctic ice sheet is larger than Mexico and sits on ground that is below sea level. That makes it vulnerable to a warming ocean, lapping at its edges. The ice sheet, however, is the bulwark for the inland ice mantle. Inland, the ground slopes downward, so without the West Antarctic ice sheet, the warm ocean could spill in.

The ice sheet, however, is the bulwark for the inland ice mantle. Inland, the ground slopes downward, so without the West Antarctic ice sheet, the warm ocean could spill in.

That kind of ice melt is hard to model, Dutton says, because humans have never seen it happen before, and scientists don’t yet understand the boundary parameters or physics that constrain the process.

“The retreat of the ice, especially in Antarctica, could speed up very rapidly. Once it retreats past the grounding line — which some think we have passed — we reach positive feedback: the more ice you melt, the more ice you melt,” Dutton says.

“The real question is how fast that process can happen, how fast can this ice discharge into the ocean?”

Geologic timescales get lost in the political cycle. In geologic time, Florida’s life above the sea has been very short. But the rocks tell a story about the choices humans have made to sustain life on Earth, and future geologists will find signs of today’s choices in the geologic record, perhaps.

“People talk about saving the Earth, saving the planet, and as a geologist you kind of have to chuckle to yourself,” Dutton says. “The planet is going to be here, the planet is going to survive.

“Will we?”

Sources:

- Andrea Dutton, Assistant Professor of Geological Sciences

- Thomas Ruppert, Sea Grant Climate and Policy Coordinator

- Kathryn Frank, Assistant Professor of Urban and Regional Planning

Related Websites:

Related Videos:

Andrea Dutton searches for the answer to melting ice sheets causing rising sea level in the Florida Keys.

Andrea Dutton discusses sea level rise with The Bob Graham Center on Vimeo.

Kathryn Frank discusses sea level rise with The Bob Graham Center on Vimeo.

This article was originally featured in the Summer 2016 issue of Explore Magazine.