Celeste McWilliams feels a surge of mother bear instinct each fall when her “babies” hatch. After monitoring their nests for weeks as part of the Sea Turtle Conservancy, often she is on hand to watch the tiny sea turtles scurry for the waves, off on a perilous journey.

“Sometimes, I want to dive in the water with them to be sure they’re OK for the next 20 years,” McWilliams says. “It’s like having little reptile children.”

As protective as she feels, she knows these turtles don’t belong to her or to any of the hundreds of vigilant volunteers on turtle nest patrol. Nor do they belong to the University of Florida scientists and scholars so invested in their conservation. They may hatch in Florida — and, if the females live, return to Florida to lay their own nests — but Florida isn’t exactly home.

Tom Ankersen, a UF conservation scholar, calls them turtles without borders. He has spent much of his career working on conservation law and international agreements to protect sea turtles, and on the surface, that global effort appears to be paying off. Green turtle nests in Florida, for example, have increased 80-fold since consistent counts began in 1989.

The surge in population has led some scientists to ask if certain sea turtle species still qualify as endangered, and others have begun discussing a new designation for one species, loggerhead turtles: species of least concern.

It’s a designation that rankles biologist Karen Bjorndal, director of the Archie Carr Center for Sea Turtle Research, even as she acknowledges the current uptick in population.

“I just cringe at this designation,” Bjorndal says, “because it trivializes the threats that these species still face.”

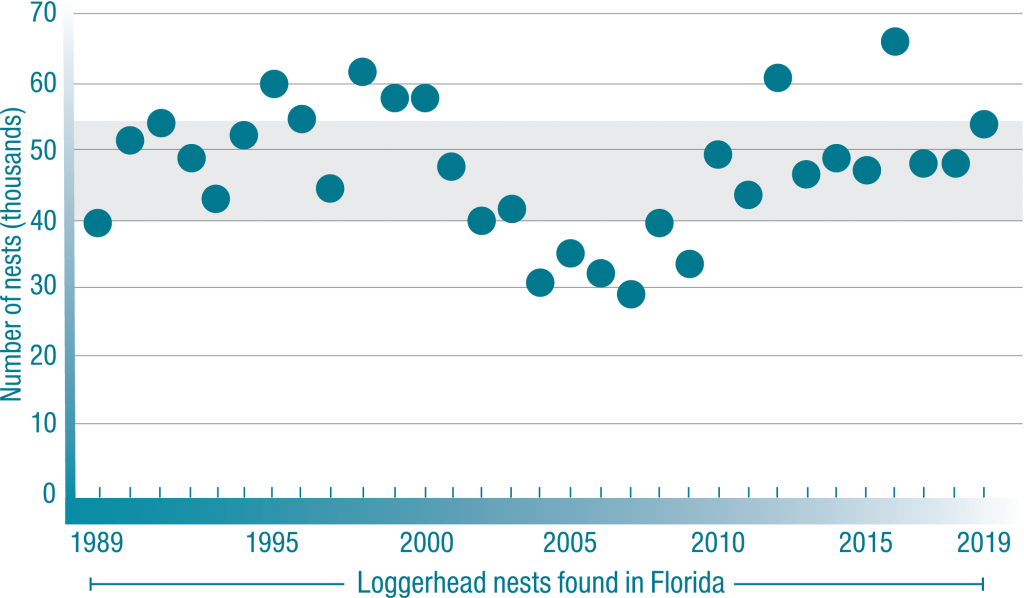

Alan Bolten, associate director of the research center, says there is still plenty of reason for concern and points to a graph on his computer screen of loggerhead turtle populations. It zigs up then down, up then down, over several decades.

“We do not understand why it went down here,” he says, pointing to a valley on the graph, “and we don’t understand why it’s going up here,” pointing to a peak.

“And that concerns us.”

The temptation to get caught up in the excitement — “thank goodness, the populations are rebounding” — is tempting, Bjorndal says, “rightfully so.”

Legions of volunteers like McWilliams have put in decades of hard work, patrolling beaches every day during nesting season from May to October, protecting the nests. Around the world, thousands of people, Bjorndal says, have made real sacrifices in terms of not eating turtles or not selling them.

“It has hit people, culturally and economically,” Bjorndal says, “so we need to celebrate; those sacrifices are paying off. We don’t want to be all doom and gloom.”

But the data still give her pause.

“If you analyze the graph, there’s no trend. Over all those years, it hasn’t increased, it hasn’t decreased,” Bjorndal says of the graph from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. “It’s stable, whatever that means. It’s the most unstable stable curve you’ve ever seen.”

Celebrate, yes, she says, but realize there’s more work to be done.

Practicing Patience

There are seven species of sea turtles, six of which are threatened or endangered, and five are found in Florida. About 90 percent of all sea turtle nesting in the southeastern U.S. occurs on Florida beaches, making Florida ground zero for conservation and a great home base for the Archie Carr Center.

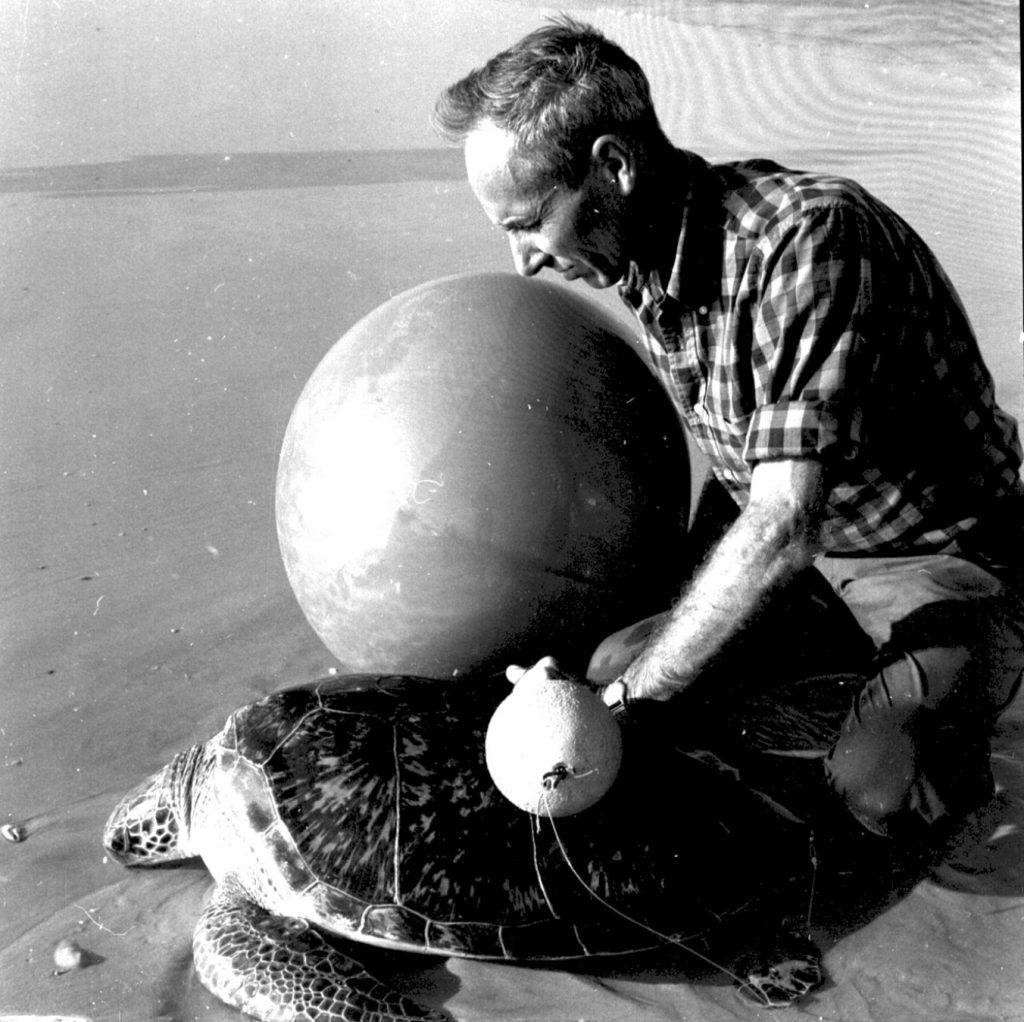

The center is named for UF conservation pioneer Archie Carr, who began his work on sea turtles in the 1950s. Bjorndal and Bolten joined the research program in the 1970s. Decades later, they say, sea turtle science is a practice in patience.

Bjorndal and Bolten have some of the longest datasets on green turtles and loggerheads. Still, the creatures live 50 to 80 years, so the scientists may reach retirement before some of their subjects age out of their studies.

“When you have an animal that has a generation time of 50 years and that takes about 30 to 35 years to reach sexual maturity, you can’t look at five- or even 10-year periods and draw conclusions,” says Bolten. “You need to look at overall population change over a generation.”

If there is a rebound in nesting or populations, as for green turtles in recent years, pinpointing what caused it — or when that event happened — is excruciatingly difficult.

Rebounding populations also come with other research questions.

As sea turtles increase, so has their grazing of seagrass beds, much to the chagrin of other stakeholders, who got used to turtle-free seagrass beds, which shelter and feed a multitude of marine organisms that had the beds all to themselves when turtles were in decline.

“We have to keep in mind,” Bjorndal says. “The natural state is the grazed state.”

Two doctoral students at the research center are exploring the question of sea turtle impact on seagrass beds. Alexandra Gulick is investigating how turtle grazing affects the productivity of seagrass beds as a system. Early results show the grazing turtles do not decimate a seagrass bed, but Gulick would like to get a better idea of the carrying capacity of the beds.

“How did the seagrass beds once function when there were a lot of turtles?” Gulick asks.

Nerine Constant is studying fish assemblages in seagrass beds, in response to comments from fishers who are concerned about sea turtle grazing because their catches are declining. Using underwater video, she is surveying fish abundance and diversity in grazed and ungrazed seagrass beds to get the data needed to make management decisions.

Bjorndal points out that the ability to do such studies is a sign of success in itself.

“For years, it was almost impossible to find a natural grazing plot,” Bjorndal says.

Years ago, one graduate student at the research center spent thousands of hours underwater, trimming seagrass with scissors to measure the potential impact of grazing if sea turtle populations rebounded.

“Now, we have the luxury of going out and finding grazed seagrass beds, and in some areas, it’s harder to find an ungrazed area than it is a grazed area,” Bjorndal says.

“It’s been such a revolution, just over my lifetime.”

As green turtles and loggerheads recover and make themselves noticed in the ecosystem, people need to keep in mind that the turtles belong there, she says, even though they have not been present in such numbers for decades.

In August, Gulick and Constant also joined a Greenpeace expedition and teamed up on a research project on the Sargasso Sea, continuing the research center’s long connection to the ecosystem.

For decades, hatchlings appeared to hatch and then disappear for years. Carr called those years the lost years and theorized the juveniles spent those important years growing and developing in the Sargasso Sea. Not long after his death, Bjorndal and Bolten proved it.

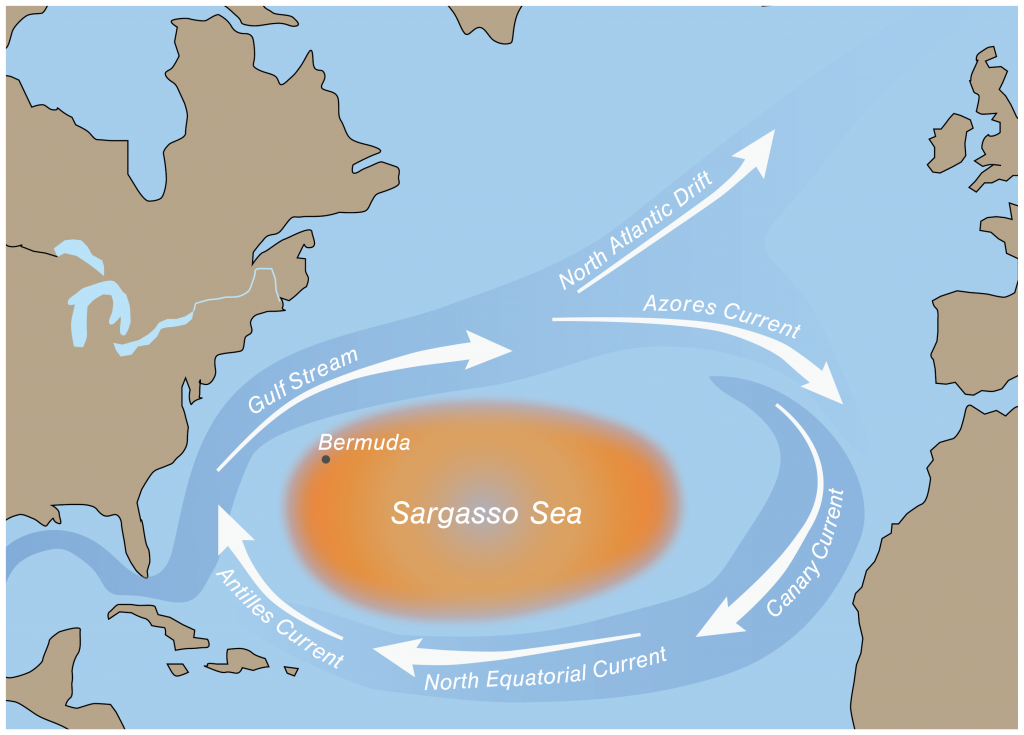

The Sargasso Sea is a sea with no shore. It sits in the North Atlantic gyre, bounded by currents moving clockwise: the Gulf Stream on the west, the North Atlantic Drift on the north, the Canary Current on the east and the North Equatorial Current and Antilles Current on the south. As the currents shift, the boundaries shift, but all the while corral sargassum, a nutrient-rich golden brown seaweed, into a huge floating mat. The biodiversity of the sea earned it the nickname the golden rainforest of the ocean.

The same currents that corral the sargassum help steer the hatchling sea turtles into the Sargasso Sea, which is about 4.1 million square kilometers, a vast nursery where they find ample food and protection from predators.

Gulick and Constant knew the turtles were using the sargassum mats for refuge and food, but had another question: Could sargassum mats be providing a thermal advantage to help the tiny turtles grow? They sampled various locations and, indeed, the sargassum floating on the water was preventing lateral water movement and exchange, keeping the water in mats warmer and potentially increasing the growth rate of the turtles, which are about 6 centimeters or so when they arrive.

Learning more about the temperature of the sargassum mats is particularly important in a warming world. While a warm watery world might help the turtles, researchers don’t yet know if there is a heat threshold beyond which the turtles would be harmed.

Climate change isn’t the only threat, though. The sargassum that shelters the turtles also traps tiny pieces of plastic. Bolten says more than 60 percent of the hatchlings coming off Florida beaches have ingested plastics after as little as two or three weeks in the water, and Constant saw evidence of that herself.

“When you swim through these mats, there’s a rain of small plastic pieces, even here, 200 miles off Bermuda and 1000 miles off the U.S. coast, in the middle of the ocean,” Constant says. “We were seeing plenty of plastic.”

While there are rules about polluting near-shore waters, there are only voluntary agreements not to degrade the Sargasso Sea. It falls in the High Seas, a sort of wild west of the ocean where no country has jurisdiction. And Ankersen is familiar with the intersection of jurisdictions and conservation law.

Turtle Lawyer

Ankersen met David Carr, Archie’s son, through his early conservation work and ended up in the late 1980s in Tortuguero, a Costa Rican beach famous for nesting by four turtle species. The conservation rules in Central America at that time were hit or miss. Some countries had protections, others were still building turtle canneries.

“I went to Tortuguero for a weekend, and I was sold,” says Ankersen, who has seen major successes in turtle protection in the Caribbean.

Closer to home, there have been successes, too, with turtle excluders adopted by fishers to keep turtles from dying in commercial fishing nets and regulations passed to protect beaches where sea turtles nest.

One key success in the last decade is something any beachfront resident can help with: changing a lightbulb.

Light is the beacon that guides the silver-dollar-sized hatchlings as they run for the surf. In an age before electricity, the ambient light on the waves guided them across the sandy beach to the waves. In the modern world, lights on decks and porches often have the tiny creatures running not to the open ocean, but into dunes and decks and pilings, where they get stranded and become easy prey for other creatures.

Today, sea turtle-friendly lighting is gaining ground, and the fingerprints of the Conservation Clinic’s work on that front show in state policies and local ordinances.

“Our model lighting ordinance has been adopted in some form or another by communities around the state,” says Ankersen, who directs the Conservation Clinic, the experiential learning arm of the College of Law’s environmental and land use law program. He also serves as director of the Florida Sea Grant legal program.

Technology, too, has caught up with policy. The type of light — blue, red or white — matters to sea turtles because of the wavelength. With long wavelength light — such as yellow or red — beachfront residents can keep the lights on and sea turtles can nest and hatch without artificial light beckoning them into harm’s way.

“Biology and technology have converged to enable technological fixes to what had been human behavioral problems,” Ankersen says.

Another project — coastal conservation easements — has met with less success, but Ankersen says the research in developing the project may lay a foundation for future work. Conservation easements allow the state to acquire rights to land in the interest of wildlife and ecosystem protection. The landowners retain ownership but agree to forego certain uses of the property in exchange for payment or tax breaks from the state and federal government.

Conservation easements for wildlife corridors through vast ranchlands in the middle of the state have been popular, protecting thousands of acres. But coastal conservation easements have turned out to be more complicated.

“From a policy perspective, there’s a preference for big, wild and connected,” Ankersen says. “Our coastline is anything but big, wild and connected. Beach properties are small, domesticated backyards and disconnected.”

The model easement that the Conservation Clinic developed offered a suite of options, and landowners could choose which options they wanted to put into practice. For example, a landowner could agree to keep domesticated animals, such as dogs, away from sea turtle nests and hatchlings. Another significant provision was agreeing not to armor the beachfront by building a seawall, which would be a barrier to a nesting turtle.

During the research phase, the clinic surveyed coastal residents region by region to determine how receptive they would be to easements. A normal return rate for such a survey would be about 5 percent, Ankersen says.

“We had a 27 percent return rate. It’s the most incredible return rate I’ve ever seen on a survey,” Ankersen says.

Heartened by the response, the team set out to engage directly with landowners, and that’s where it got more difficult.

“It’s one thing to love sea turtles and think abstractly about giving over some property rights,” Ankersen says. “Signing on the dotted line is more problematic.”

Most people — or their heirs — were not willing to sign away their right to armor their beachfront against future sea level rise, storms or erosion. The team ended up with one easement, on spit of undeveloped beachfront. Still, Ankersen says, it’s important as a test case and may help in current work developing easements on privately owned islands in the Bahamas.

“The research, from tax law to property law to the surveying, was all done with students and faculty,” Ankersen says. “And that’s out there, and bits and pieces are being used.”

One approach that grew out of the research was to adapt the easement language for use in management agreements among consenting beachfront neighbors. The agreement does not entail transfer of property interests but it creates a common management approach for the beach. One such agreement exists in the Keys. A sea turtle-friendly model lighting easement that operates much like a façade easement in a historic district also has been developed.

The clinic is working on two other fronts as well, one on beach renourishment — sea turtles are picky about the beach slope and sand in which they nest — and another on surveying coastal park management plans to see how friendly they are to sea turtles. Again, Ankersen says, jurisdictions matter. If one coastal county has robust protections and good beach management, but the county to the south does not, then protection for sea turtles suffers.

In the meantime, Ankersen says conservationists rely on the army of sea turtle monitors like McWilliams, who watches both on the beach and online as she follows the travels of turtles equipped with satellite transmitters, who nest and return to the sea.

“I go online every day to see where my girls are,” McWilliams says. “It’s literally like having more of my own children.”

Bjorndal, too, tracks turtles, watching as they whip through dozens of national jurisdictions.

“We released one, a sub-adult male from our major feeding area in the southern Bahamas, and he went straight south, into Venezuelan waters, circled north, went by Panama and off Costa Rica and did a whole circle then continued on up into Nicaraguan waters, where he stayed for six months,” Bjorndal says.

The turtle’s travels ended with an encounter with a fisher in the Caribbean, who returned the transmitter. More work to be done.

Sources:

- Karen Bjorndal, Distinguished Professor and Director, Archie Carr Center for Sea Turtle Research, Department of Biology

- Alan Bolten, Associate Director, Archie Carr Center for Sea Turtle Research, Department of Biology

- Tom Ankersen, Professor and Director, University of Florida Levin College of Law Conservation Clinic

Related story:

Related websites:

- Archie Carr Center for Sea Turtle Research (ACCSTR) at the University of Florida

- University of Florida Conservation Clinic

This article was originally featured in the Fall 2019 issue of Explore Magazine.