Clyde Fraisse is eager to talk to farmers about climate change. Farmers? Not so much.

“They are very focused on this season,” says Fraisse, an associate professor of agricultural and biological engineering at the University of Florida and director of the Southeast Climate Extension project. “They are not as concerned, yet, about the end of the century.”

As he looked for ways to start a climate conversation and keep it going, Fraisse came up with a solution: an app.

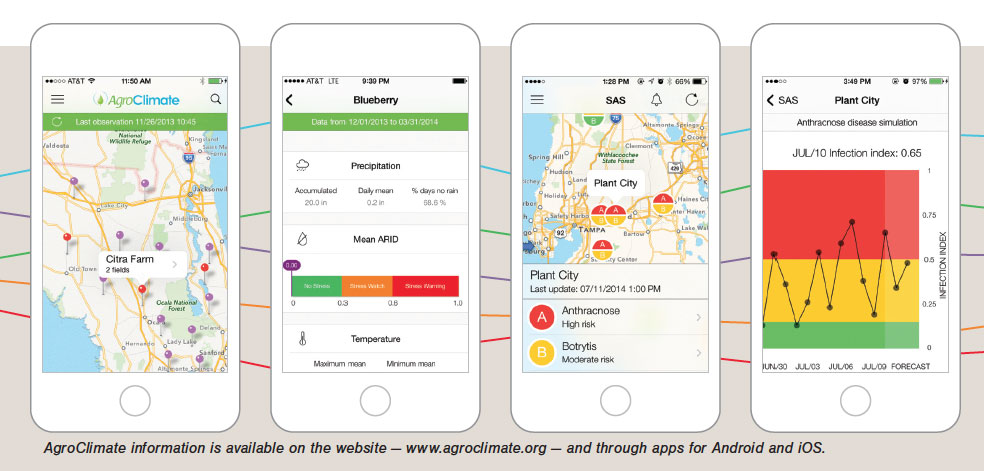

What started with a single app has now become a suite of apps that monitor weather conditions and disease threats and offer daily summaries. They can be tailored to one field, taking into account soil type, crop, planting date, and irrigation management, and offer alerts based on these conditions.

For strawberry disease alerts, air temperature and leaf wetness duration are updated every 15 minutes, offering nearly real-time notifications of disease risk levels. In case of moderate or high risk the app asks a few questions, and based on the answers, offers advice on whether to spray fungicides.

For weather data, the apps rely on UF’s 41 stations in FAWN, the Florida Automated Weather Network and five additional stations that were installed to better cover strawberry production regions of the state. So far, Fraisse’s team is up to nine apps, and counting.

The apps are a powerful farming toolbox that can travel in a farmer’s hip pocket into the middle of a field, where he or she can access data and make decisions on the spot.

“Farmers want this information on their cellphones,” Fraisse says. “They don’t want to wait to go home and open up the computer. And they don’t have to.”

Information is the lifeblood of farming, but it’s also a key to adapting to climate change, Fraisse says.

“There is a current push for sustainable intensification of agriculture, to produce more with less in order to feed a global population of over 9 billion people by 2050,” Fraisse says. “If we don’t incorporate climate science in the process we cannot do that.”

The tools Fraisse and his colleagues have worked on, available at www.agroclimate.org and by app, became so popular that he had to overhaul the database. Now, a new state can join and be added in a week. A blueberry advisory system will be added soon, and a team is working with gridded data from NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, to offer finer detail.

The tools are so popular that the USDA, which funded the original Southeast Climate Extension project at $5 million, has asked Fraisse to adapt the AgroClimate app for Nebraska. A pilot project is in place in Mozambique as part of the Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences’ international program and the team has been invited to Kenya this summer.

The value of the tools is they can be used right now, and that value grows in leaps and bounds as data are added. Farmers will be able to make adjustments in the decades ahead based on the database as it grows.

“If you’re a farmer, increasing your resilience is a win-win,” Fraisse says. “Whether you believe in climate change or not, whether you believe we are causing it or believe it is natural, it doesn’t matter.”

While croplands are not a carbon sink such as forests, per se, adding organic matter to the soil improves soil quality while sequestering some carbon from the atmosphere. Improved soil quality can increase water holding capacity, helping crops withstand longer dry spells and increasing the infiltration that helps with more frequent extreme rainfall events.

“This is good for you,” Fraisse says.

“Climate can be part of the decision tool set, even if it’s not part of the strategy for this season.”

The most popular tool this winter has been the chill hours tracker. Temperate fruits such as strawberries, blueberries and peaches all need chill hours in the winter months to grow healthfully until harvest. December, however, was so warm there was basically no accumulation of chill hours. That may be a seasonal blip, but by collecting data over decades, farmers can determine if it’s a trend, and if so, change to a low-chill variety more suited to warmer winters.

Extreme weather events — droughts and excessive rainfall, for example — also focus farmers’ attention on potential climate extremes. Severe storms open a door to discussion about the future, something Fraisse accommodates with events like field days and a yearly climate adaptation exchange that started in 2012 in Quincy and is set for this summer in Citra at the UF/IFAS Plant Science and Education Unit.

Fraisse says some of his best conversations come at small farm trade shows, where growers can test the tools and ask questions. Organic farmers for example, pay close attention to monitoring systems, because once a problem is established in their crops, they have no chemicals to take care of it.

Another area Fraisse has worked on is the carbon footprint of a crop. Production, storage, and transportation of a pound of strawberries in Florida, for instance, emits about 0.7 pounds of CO2e (carbon dioxide equivalent), under some assumptions, such as traveling from Plant City to Atlanta. The assumptions can be changed by users of the AgroClimate web site, allowing them to evaluate the impact of alternative production practices and transportation distances on the carbon footprint.

A precise carbon footprint would require very detailed information, Fraisse says. For example: Is irrigation diesel-powered or electric, and if electric, is it powered by coal or hydropower or nuclear or natural gas? How far did the crop travel, and how many boxes were on the truck, or train? How much nitrogen was used to fertilize?

In the future, if farmers seek carbon credits for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, those calculations may become worthwhile, Fraisse says, maybe even worth developing an app.

“Increasing climate literacy is the first step,” Fraisse says. “I think our farmers in Florida are much more climate literate than they were 10 years ago.”

Source:

- Clyde Fraisse, Associate Professor of Agricultural and Biological Engineering

Related Website:

This article was originally featured in the Summer 2016 issue of Explore Magazine.