Most spiders don’t see in color. Not so for jumping spiders, tiny show-offs who flaunt their vivid stripes and fluffy tufts in jazzy courtship dances. The six thousand species in the Salticidae family live in a world awash in vibration and chemical signals and have a 360-degree view from four pairs of eyes that encircle their head like a crown. So why did they need to evolve color vision as well?

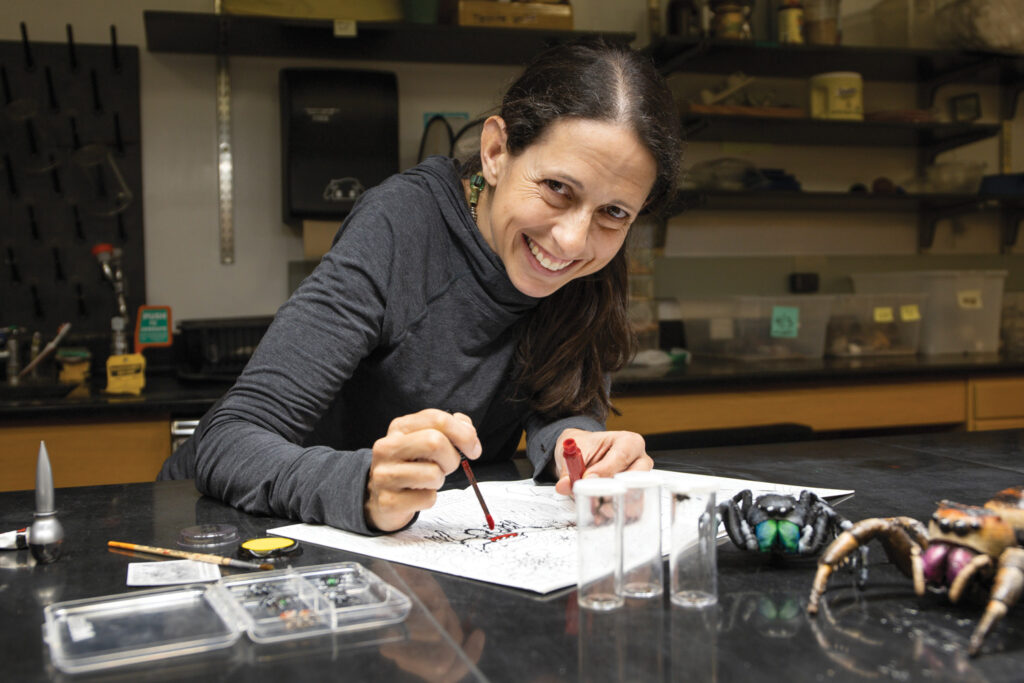

Entomologist Lisa Taylor has some theories, and to test them, she and her lab members get artistic. By altering spiders’ patterns with eyeliner — no small task for a subject not much bigger than a ladybug — they explore how color affects mating. And by painstakingly painting termites different colors, they can see if jumping spiders use their enhanced vision to avoid the bold colors that can signal poisonous prey. Conversely, vibrant vision could also make it easier to spot prey: Taylor recently discovered that a species in Kenya can see the blood in a well-fed mosquito, which could help it find the juiciest meal.

Scientists once thought jumping spiders couldn’t see red at all, as most only have receptors for green and ultraviolet light. But in 2015, Taylor and her colleagues found that some species use a filter in their retinas to shift some of their green receptors to red. The Kenyan mosquito-eating species, however, doesn’t have that filter — meaning it developed another, still unknown way to see red. Overall, the family evolved color vision at least three separate times, which Taylor calls “really weird.”

“Color vision usually happens once,” she says.

Why do spider senses matter? Learning to fit sophisticated optics in a tiny package could pave the way for sensors small enough to use in wearable technology, microrobots, or augmented reality devices.

“There’s a lot in the basic science that applied scientists can use,” Taylor says. “I’m driven by curiosity: How can spiders perceive and process so much information in such a noisy world, and how do their brains make sense of all that information?”

That’s a superpower we could all use.

For more on this research, listen to Lisa Taylor on the WUFT podcast Tell Me About It.

Visiting the Florida Museum of Natural History’s Spiders Alive! exhibit? Head to the museum’s West Gallery for a look at Taylor’s research. Spiders Alive! runs through Sept. 4.

Lead photo courtesy of Colin Hutton.

Source:

Lisa Taylor

Assistant Research Scientist, Entomology and Nematology

lisa.taylor@ufl.edu