University of Florida history Professor Jack E. Davis has made a career out of writing about big environmental topics. He won the Pulitzer Prize in history for his 2017 book The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea, and now he’s got a new book out titled The Bald Eagle: The Improbable Journey of America’s Bird.

Among the many interesting facts about the rise and fall and rise again of the bald eagle that Davis describes are several about the role Floridians, and University of Florida scientists in particular, played in bringing the bird back from the brink of extinction.

Here are some excerpts Davis chose to summarize the nation’s history with the bald eagle and UF’s role in saving it.

Reverence and Recrimination

The bald eagle has been associated with higher principles and better attributes since 1782, when Congress made it the central figure on the Great Seal of the United States. Representing fidelity, self-reliance, strength, and courage, the founding bird quickly attained a vaunted perch in America’s iconography. Its visage appeared on the U.S. Capitol dome and pediments, hard and paper currency, business and sports-team logos, coat buttons and cuff links, and the 101st Airborne’s sleeve patch …

Yet no animal in American history, certainly no avian one, has to the same extreme been the simultaneous object of reverence and recrimination. For centuries, eagles risked their lives flying across American skies. People familiar with the history of the bald eagle generally know that in the mid-twentieth century, DDT nearly eliminated the species in the contiguous U.S. Fewer know that before then the bald eagle’s existence was gravely threatened by something as equally toxic as that lethal chemical pesticide: myths, lies, and insensitivity. False accusations [of livestock pilfering and baby kidnapping] fostered a cross-eyed vision of a morally depraved predator and thief …

For more than a century before DDT’s commercial introduction, Americans prosecuted a fierce coast-to-coast assault directly against their flagship bird. The aggression was nothing short of premeditated and acceptable — legally and socially. Anyone anywhere in the position to do so squeezed the trigger and carried out the bird’s execution — respectable, hardworking, churchgoing people who thought they were doing no more harm than pulling up an annoying dandelion …

All this is to say that twice, not once, the United States nearly lost its flagship bird from the wild, and twice people aided its return. The first time, the Bald Eagle Protection Act of 1940 sought to stop the century-long bloodshed and establish a peaceful accord between Americans and the persecuted species.

Author’s Note

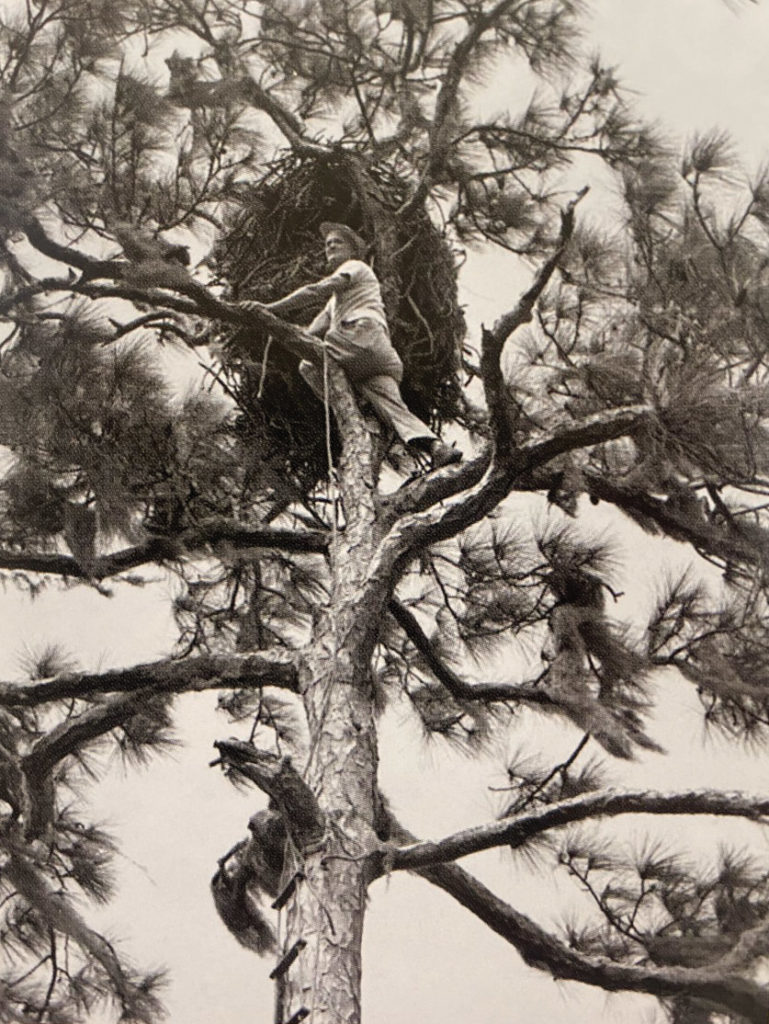

The bill had previously failed in Congress after experts testified that bald eagles were nonmigratory birds, arguing that federal protection would encroach on a state’s authority over resident birds. The individual who brought new light to bald eagle migration was Charles Broley, a blue-eyed Canadian banker who retired to Florida. Broley began banding eagle nestlings in the 1930s, when no one was duplicating his efforts elsewhere. The following passage describes his first climb up a nesting tree. He climbed over 1,100 trees over the next 20 years to prove that bald eagles migrate across state and national boundary lines.

Precipitous Decline

Aloft in the eyrie, safe at home, were two young bald eagles. Five or more pounds each, physically the size of a rugby ball, they were nearly ready to experience the brilliance of flight. Their eyes were dark, their feathers too. The spiky ones on their heads drew back as if a stiff wind were perpetually blowing in their faces. Their legs, feet, and beaks were leather colored, their talons black and long. They were alone together in the nest and safe. At five to six weeks, eaglets are typically left unattended while their parents are off fishing or hunting, giving the young room to romp and exercise. By then, they are too big to be preyed upon by an owl or a hawk, and they have their talons, four on each foot — eight lethal pirate hooks. Eaglets growing into juveniles are to be avoided, not accosted.

Yet there are always violations of what’s expected, such as when an odd, unfamiliar creature … appeared at the edge of the two eaglets’ security … Its intense blue eyes fixed on the young birds. They backed away to the far side of the nest, beaks open, narrow tongues protruding, hissing. The smaller of the two balanced clumsily at the edge. The odd figure, about to become an unquestionable threat, stretched forward and reached for the teetering eaglet. It jumped. The falling youth instinctively opened its wings and, slack on the air, glided safely into a clump of saw palmettos.

The blue eyes then turned on the other eaglet and reached out again. The eaglet sensed a grip around one of its wings and, fighting back, drew blood but could not free itself. It felt something around one of its feet, small and metallic, clamping but not restraining. The intruder let go, and the frightened bird scrambled back and away, watching as the blue eyes dropped back below the nest.

On the ground, the intruder crashed through stiff, green fronds of saw palmettos, where the second eaglet was hiding … Danger pushed closer. The grounded bird panted. Fronds opened, and sunlight and the blue eyes fell on the eaglet. It scrambled off, flapping its wings, using them as weapons. The pursuer persisted. The bird was seized, its wings and legs arrested. As with its sibling, something metallic went around one of its feet, but this eaglet was not set free.

A soft cover fell over its head of spiky feathers, and all went dark. For a long period the eaglet was in a blinded, free-floating space, tugged about at times, swaying at others. Finally, light appeared as the cover was lifted off. The eaglet was back in the nest. Its dark eyes found its sibling, and it clambered over and away from the intruder, watching the strange being slip down and out of sight.

Author’s Note

By 1959, when Broley was 79 and had climbed his last tree, he had banded 1,240 eaglets. That number would have been much larger if not for DDT, which went on the commercial market in 1945. Banding eaglets made him witness to the species’ precipitous population decline, and he was one of the first to link the pesticide with bald eagle mortality. Rachel Carson noted his work in Silent Spring. A year after its 1962 publication, the eagle population fell to fewer than 500 nesting pairs in the lower 48 states, and in 1972 the EPA banned the domestic sale of DDT. Subsequently, University of Florida scientists, in collaboration with the George Miksch Sutton Avian Research Center in Oklahoma, launched an egg translocation program using Florida eagles to repopulate southern states ravaged by DDT.

Egg Recycling

Nobody had ever pursued this approach [egg translocation] with eagles, and understandably, it had skeptics … The central question was whether the Florida breeders would produce a fertile second clutch of eggs after researchers took the first from their nests. Despite apprehensions, everyone agreed to give [the] plan a try. Mike Collopy, who was head of wildlife and range science at the University of Florida, and a self-confessed doubter, collected eighteen eggs from Florida eagle nests in December 1984. The eggs successfully hatched at Sutton. At eight weeks old, the unfledged juveniles were relocated to hack sites [large elevated outdoor cages] in Oklahoma and two other states, and after they fledged, they took off to carry on life in those states. The Florida eagles that had unwittingly donated eggs indeed double-clutched, and their new eggs hatched. This exciting development convinced everyone that such “egg-recycling” was possible.

At the start of the next season, Petra Wood, a graduate student who worked with Collopy, conducted a weekly aerial reconnaissance of fifty to sixty nests in north-central Florida … Wood flew with Florida Game pilots, surveilling the piney backwoods of a six-county area in north-central Florida. Unlike other parts of Florida, not much below the plane had changed since William Bartram had traveled through the area two centuries earlier and complained about the thieving ways of bald eagles. In the 1920s, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings made a home in the region at Cross Creek, and set many of her stories and books in the rural hinterland … Rawlings described the bald’s eyrie ungraciously as a “ragged cluster of sticks in a tall tree.” Yet of the hamlet of Cross Creek, she said, “There is no magic here except the eagles.”

Ace fliers, the pilots would circle one of those ragged clusters of sticks while keeping the nose of the Cessna pointed on it. Wood, trying to keep her last meal down, would look for eggs and the practicality of access for a ground crew, which would include a climber and a small contingent from the Sutton Center. The tree jock would strap on climbing spurs and ascend each host tree. The vibration referring up the trunk from his spurs daggering into the bark and sapwood was usually enough of a fright to flush the sitting parent. Upon reaching the nest, the climber would put on a surgical mask and gloves to prevent contamination and carefully place the eggs in a padded cylinder cinched to a long rope. “Eagles pick the most majestic views in the world,” one intrepid tree jock told a writer for Life magazine. “Up there, surrounded by the wind, a sense of awe comes over me. I feel like I should recite some sacred incantation.”

Someone might have been reciting one for getting the eggs to Oklahoma. Transporting them nearly thirteen hundred miles was a risky undertaking. The Sutton team had come down in a motor home and driven the twenty-plus-hour return trip straight through. Rotating duties, one person would drive, another would sleep, and the third would sit with a pillow on their lap with the incubator on top. The eggs were kept at 99.5 degrees Fahrenheit, with no more than a half-degree deviation. Every three hours an alarm would ding to remind the team to turn the eggs, as do the parents, to keep the embryos from sticking to the inside of the shell.

When eggs arrived at Sutton, those with thin shells stayed in an artificial incubator. Others were placed underneath Cochin hens … They are accomplished sitters. Still, a shell would occasionally crack, and the staff would rush in like all the king’s horses and all the king’s men with superglue and mend the egg … Incubation ran approximately thirty-six days, and hatching took approximately thirty-six hours …

Starting out at three to four ounces, chicks reached about five pounds in four weeks … [Caretakers] screened themselves from the eaglets and fed them using a hand puppet with a latex eagle head and black sleeve. The eaglets ate well, sumptuously treated to a mixed diet of Japanese quail, rabbits, lab rats, and roadkill deer. In their eight-week stay at Sutton, each consumed the equivalent of eight hundred quail … At about eight weeks of age, when their dark-brown juvenile feathers were grown in, the eaglets were moved to hack sites in one or more of five states: Oklahoma, Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, and Mississippi.

Author’s Note

Today, the lineage of many nesting bald eagles in these states can be traced to Florida birds. Over a seven-year period, they contributed 275 eggs to science. Thanks to restoration programs across the country, and the species’ evolutionary instinct for self-preservation, the bald eagle population now stands at approximately 500,000 across the continent, the estimated number that existed when Europeans first settled North America.

The Bald Eagle: The Improbable Journey of America’s Bird is available at wwnorton.com and wherever books are sold.

Source:

Jack E. Davis

Professor of History

davisjac@ufl.edu