The couple was baffled. Like millions of other people, they had logged on to the website of Project Implicit and taken a test to measure their implicit biases, or biases that may be hidden, even from ourselves.

The result was so counter to their lived experience that they used an email link at the end of the page to ask a question.

Christine Vitiello, a doctoral researcher in the University of Florida’s psychology department, was taking her turn responding to such emails that day.

“They did not believe the result,” Vitiello recalls. “They said, ‘There’s no way I am biased in this way.’”

The interracial couple’s actions — marrying outside their race and having children — were a conscious demonstration of egalitarian beliefs. Explicit beliefs. The test result, however, showed an implicit association of white faces with positive words and black faces with negative words, indicating an implicit bias.

Vitiello says the researchers in the Attitudes and Social Cognition Laboratory respond to six or seven such emails a day, often from people who are similarly perplexed.

“Sometimes people will tell their life story to explain how the test result cannot be real,” says Vitiello, who is collaborating with Elsa Jiang on research about implicit bias.

Test-takers, like the interracial couple, usually accept the results after researchers explain that a test result is not a matter of consciously held beliefs. Jiang and Vitiello’s mentor, UF psychology Associate Professor Kate Ratliff, says that implicit bias is often difficult for people to comprehend, sometimes so difficult that test-takers question the validity of the test. However, recent research shows that test-takers report the experience as more positive than average.

“A common response is defensiveness. The other response we see a lot is guilt, when the feedback differs from how people see themselves,” said Ratliff, the executive director of Project Implicit and director of the Attitudes and Social Cognition Lab.

But after 17 years and 25 million tests, Ratliff says Project Implicit has stood the test of time.

Testing Bias

Anyone can take a test — or all 14 — by logging on to the Project Implicit website. There are 14 tests that measure implicit bias in gender, age, religion, weight, sexuality and other areas. A Hispanic implicit association test and a transgender test are in the works. At international sites, people can take the test in their first language.

These are associations we have in our minds regardless of whether we want or believe them. These are the kinds of biases that are less controllable.

Kate Ratliff

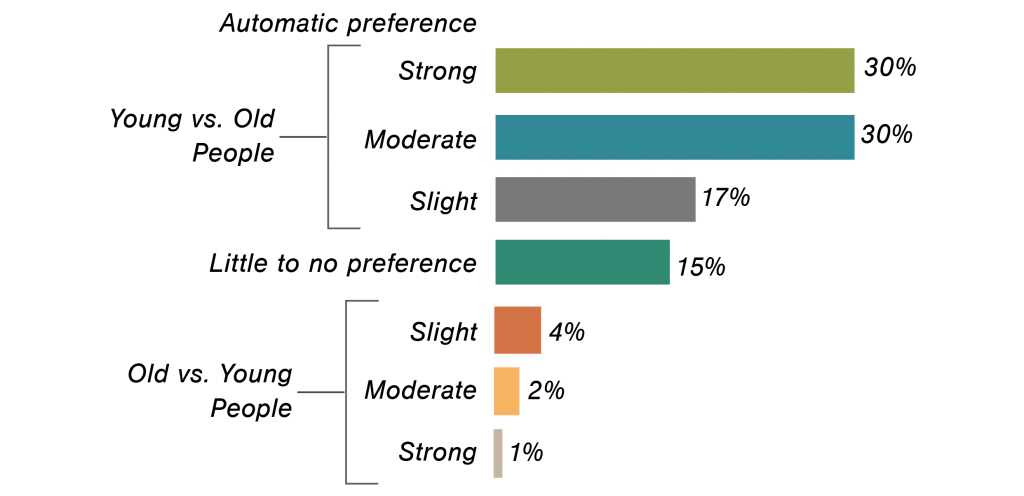

After logging on to the site, test-takers answer questions about their attitudes and demographics. When the test starts, participants match good and bad words with images, such as images of young and old people for the age Implicit Association Test. The test keeps track of reaction time as test-takers match old and young faces with positive and negative words. A result for that test is something like this: “In the IAT you just completed your response suggested a moderate automatic preference for young people over old people.” A bar graph follows showing where a test-taker’s result fits among all results for that test. It turns out that 30% of the tested population has a strong automatic preference for young people over old people. Only 1% of the tested population has a strong automatic preference for old people compared to young people.

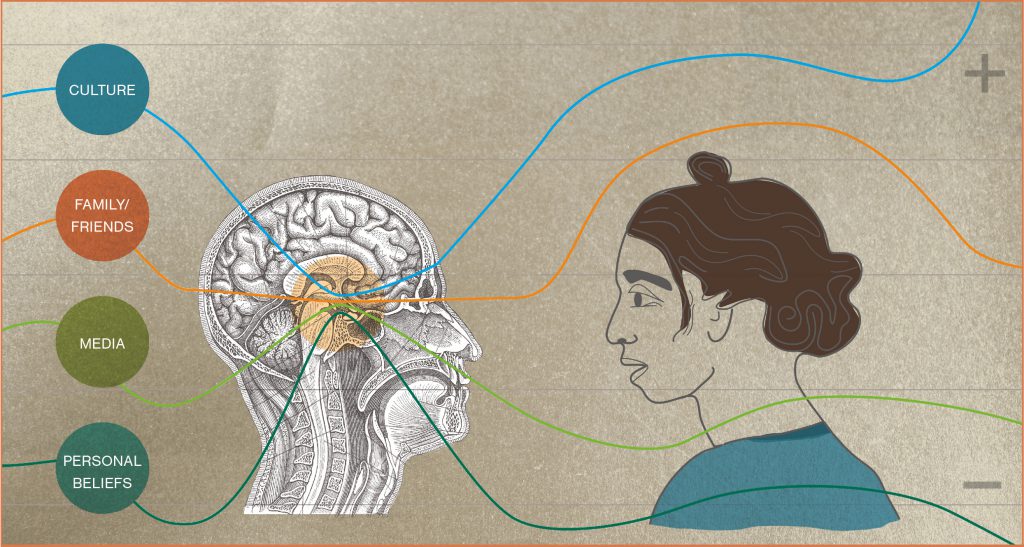

The test measures implicit bias, not explicit prejudice. Ratliff says people are aware of their explicit prejudices and the stereotypes they embrace. Implicit bias, she says, can be influenced by forces outside our awareness and control.

Bottom: Project Implicit Participants by Race

“These are associations we have in our minds regardless of whether we want or believe them,” Ratliff says. “These are the kinds of biases that are less controllable. We can’t introspect on them. We have to use scientific tools, we have to use evidence of actual behavior, observable things, to uncover and quantify these more implicit biases.”

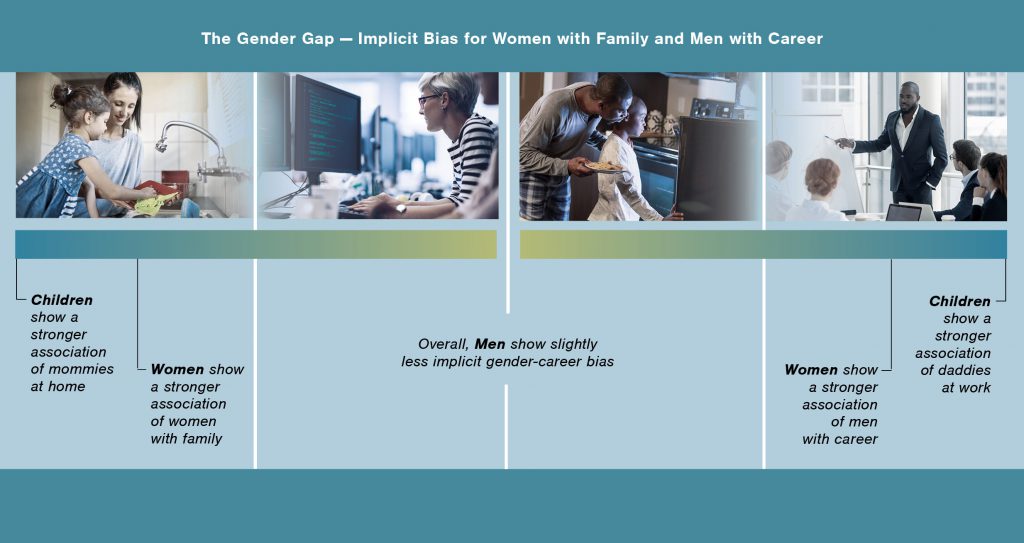

For many tests, group membership is a good predictor of an implicit bias, such as members of an ethnic group having a strong positive preference for their own group. But some tests show that group membership is not a good predictor, such as the gender-career implicit association test.

In that test, about 75% of participants have an easier time associating women with family and men with career than the reverse. Interestingly, Ratliff says, women show these effects just as strongly as men do. Even more interesting, most participants say they equally associate men with family and women with careers, the opposite of what the test shows.

That’s the important takeaway, Ratliff says.

“What people say they have in their minds doesn’t always match up particularly well with what we can see from other kinds of observable behaviors that don’t rely on people’s self-reports,” Ratliff says. “Our implicit biases often contradict our stated beliefs.”

Implicit bias can be influenced by forces outside our awareness and control.

Data Mining

With more than 25 million tests completed since 2003, Project Implicit’s huge dataset is ripe for mining for all kinds of research, and several of Ratliff ’s doctoral students are doing just that.

Jiang and Vitiello are collaborating on a study to determine whether states with a high gender-career bias — that is, a higher association of males with career and females with family — have a higher suicide rate than states with a lower bias.

So far, Jiang says, they have found that states that exhibit the higher gender-career bias do have a higher suicide rate for females. But, surprisingly, they found that those states have a lower suicide rate for males than states with lower gender-career biases. Jiang and Vitiello say more study will be needed to determine whether the higher gender-career bias has a protective effect for males, while it makes women more vulnerable.

Jiang and Vitiello say these biases often reflect culture.

“Children from very early ages often have this association that mommies are at home with children and daddies go to work, even if they’re not in a family that endorses that,” Vitiello says. “It’s something we’ve been trying to unravel. How much of implicit bias is from the culture?”

Samantha Douglas also is using the gender-career test results and says trying to tease apart a stereotype is less straightforward than analyzing a bias toward a group identity, such as an ethnicity. Women consistently show a stronger association of women with family and men with career than men do, even though they don’t acknowledge it.

“In explicit questions, many women say they don’t have gender-career bias, but they do often show it implicitly on the IAT,” says Douglas, who is working with psychology Assistant Professor Colin Smith, the director of education for Project Implicit. “People might expect men to show a stronger association of women with family and men with career than women do. But actually, women show a slightly stronger implicit association of women with family and men with career.”

Sorting through the “why” behind the test results is turning out to be tough to investigate. Douglas says she has used a gender roles belief measure and looked at hostile and benevolent sexism in futile attempts to explain the phenomenon. She has also compared test results against an assortment of other demographic data, such as whether someone is a parent, or married, or employed.

“That doesn’t seem to explain the effect, either,” Douglas says. “It’s really just been a big mystery.

“With a stereotype, it’s really hard to pull apart all the relationships,” Douglas says.

Influencing Behavior

We have the biases. So how do we stop them from leading us to behaviors and judgments and decisions that we don’t want?

Kate Ratliff

Ratliff says implicit bias is an example of how much of our mental life occurs outside our active awareness. So far, she says, there are not many scientifically supported strategies for changing implicit biases, but we may be able to learn how to keep implicit biases from influencing our behavior.

“These things we have in our mind that we’re not aware of influence what it is that we actually do,” Ratliff says.

Egalitarian ideas and rules and regulations — in hiring decisions, medical treatment, the criminal justice system, the workplace, the media, housing — can be thwarted by implicit biases.

“We have the biases,” Ratliff says. “So how do we stop them from leading us to behaviors and judgments and decisions that we don’t want?”

Strategies like blind auditions can keep bias from entering into a decision. In a blind audition, musicians perform a musical piece behind a curtain, keeping their gender, age, ethnicity, race and other identifying factors hidden. The decision to hire a musician can only be made based on one factor, the musical performance.

“That doesn’t change the bias, but it could change the outcome,” Ratliff says. Some biases are a “chicken and the egg problem,” Ratliff says. In India, one province passed a rule that half the council members had to be women, and women went from holding none of the seats to holding half. That had an effect on people’s attitudes toward women.

“We have these biases that prevent women and people of color from getting equal power, but the fact that they don’t have equal power perpetuates the bias,” Ratliff says. “Here, changing the power structure influenced people’s attitudes.

“If we really want these deeply ingrained kinds of associations and biases to change, then our society has to change, because that’s where we’re getting them,” Ratliff says.

Source:

Kate Ratliff, Associate Professor of Psychology

Related website: