In 2006, specialists around the country started getting emails from a recent Harvard grad named Eric Wang asking about myotonic dystrophy, an inherited disease that runs in his family.

It wasn’t unusual for them to hear from loved ones of patients hoping for a breakthrough, but this was different. Wang had one question: What do you need to know to find a cure?

His plan: devote his career to filling in the gaps, developing treatments for his dad and millions of others worldwide.

“It’s not common for a talented young person to declare a serious intent to work on myotonic dystrophy,” says Charles Thornton, a neurologist at the University of Rochester who received the email. “In the case of Eric Wang, I am very grateful that he decided to go in this direction.”

Family Medicine

Wang was 8 when his father was diagnosed with the disease, which intensifies over generations, robbing mobility, heart and cognitive function, and energy. Some of his relatives are unaffected or have few symptoms, while others have died. After finishing his degree in biochemistry, Wang was about to go to medical school when he started thinking there might be a better way to help. He knew his dad was running out of time.

Like Huntington’s disease and some types of ALS, myotonic dystrophy is a repeat expansion disorder, where extra copies of a genetic sequence in the protein-coding gene DMPK interfere with RNA processing, confusing or interrupting the instructions cells and tissues receive. Thornton and other experts who replied identified the same opportunities: Scientists needed to change their one-gene-at-a-time approach to encompass the whole genome and leverage high-throughput sequencing to tease out the workings of different types of RNA.

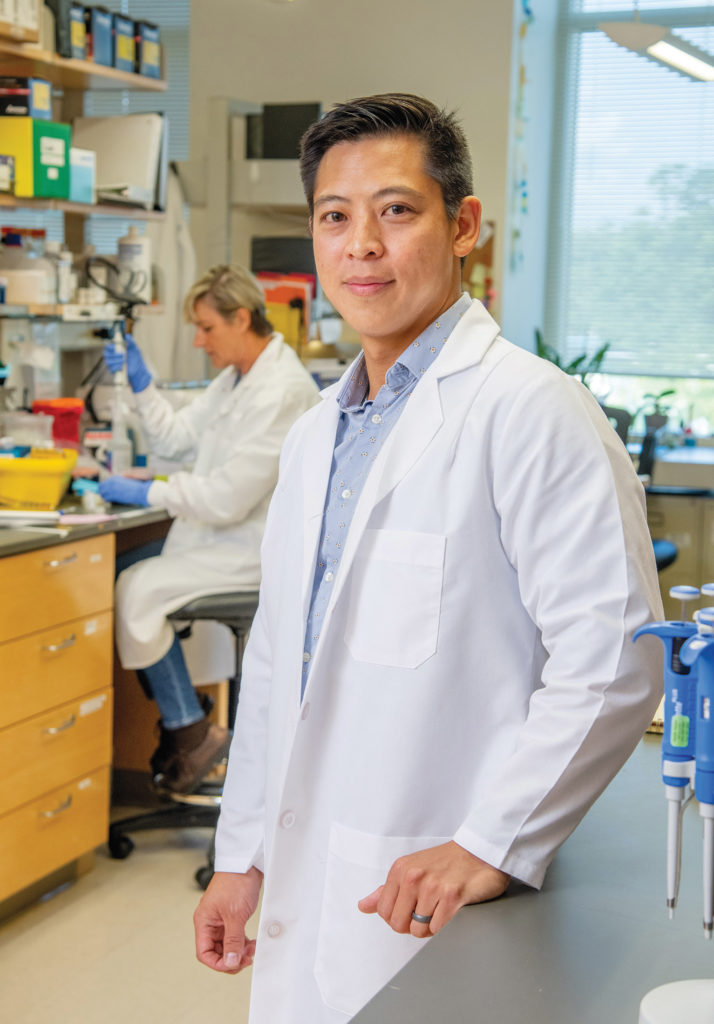

Wang took their advice to heart, dropping the med school plan and instead studying bioinformatics and integrative genomics at the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology. An NIH Director’s Early Independence Award allowed him to skip a postdoc and launch his lab at MIT. In 2015, he joined UF’s Center for Neurogenetics.

“There’s nowhere else in the world that has this concentration of basic scientists and clinical researchers working on this class of diseases,” he says. “There’s a whole ecosystem here you can’t just build right away, with clinical trials, the McKnight Brain Institute, the Genetics Institute, the Myology Institute — we have all the pieces in place.”

Still, he feels the clock ticking.

“When I was in grad school, I thought, ‘We’re definitely going to have approved drugs soon.’ I’m 40 now. I’m close to halfway through my life,” he says. “What keeps me up at night is making the right decisions about how to spend my time, because time is the most limiting reagent.”

Advancing toward a cure

In 2018, help arrived in the form of a $2.5 million award from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. The unrestricted funding — designed to pursue ideas that might be deemed too audacious for other agencies — allowed him to build and staff a lab that doesn’t have to choose between unraveling the basic science behind the disease and developing therapies for it. His team of 20 now tackles both simultaneously. Some lab members focus on gene therapy, others study how repeat expansions cause symptoms, or on the details of how thousands of mRNA and hundreds of RNA binding proteins travel through the body, which Wang likens to passengers getting on a bus.

“How do different molecules recognize their vehicles? How do they know what bus to get on? What’s the code that underlies it? The process is important to understand,” he says.

In Wang’s lab, students don’t have to choose between translational and fundamental science, says second-year graduate student Juan Arboleda, who joined as a technician in 2017.

“What’s inspiring to me is that everyone contributes to the translational work,” Arboleda says. “It’s cool to see the basic science coming into play for therapeutic projects. You’d never be able to repair a plane unless you first know how it all works.”

It can be frustrating studying aviation, though, when what you really want to do is board a flight. Wang feels the tension between time spent on basic science and therapeutics, especially when he talks to his father, who now uses a wheelchair and a pacemaker and battles brain fog and fatigue. His dad has a doctorate in physics, and the two always bonded over their love of scientific discovery. Now, “even my ability to communicate with him in the same way that I used to has changed,” Wang says.

He knows therapeutics hinge on the basic science. And he knows his relatives — and many others — are counting on him allocating his hours the right way. He takes comfort in the strides he’s made toward addressing the deficits he asked about 16 years ago.

“That gap has been filled,” he says. “The genome-wide approach happened, and not just in myotonic dystrophy. Taking things from a one-gene, one-pathway approach to the genome-wide approach has been one of our major contributions.”

Discoveries from his lab have been licensed to biotech companies and used in clinical trials. And advances in deep sequencing are helping identify how the disease disrupts gene expression and RNA processing: A microwave-size machine in his lab can run 3 billion sequences overnight, which would have been unimaginable when he started this work.

“We’re much closer, but there’s still so much we don’t know,” Wang says. “We need more people working on this to change the landscape.”

The eager student who sent those emails to top scientists in 2006 now collaborates with them, “and likely will be the leading American researcher working on myotonic dystrophy,” says Thornton, the University of Rochester neurologist.

“Our field would be a very different place if Eric was not in it. One person can make a huge difference, and he certainly has.”

Photos by John Jernigan

Source:

Eric Wang

Associate Professor of Molecular Genetics & Microbiology

eric.t.wang@ufl.edu

Hear the Story

The audio version of this story is available on our YouTube.