W

hether it’s using geographic information systems to help IFAS researchers rebuild oyster reefs or computer vision and large language models to make collections at the Florida Museum of Natural History more accessible, UF’s George A. Smathers Libraries have come a long way since its first building opened a century ago with 40,000 books that could only be read in the building.

Today, the UF libraries are a state-of-the-art academic resource system that has evolved to play a pivotal role in advancing research across disciplines, leveraging cutting-edge technology and fostering interdisciplinary collaboration. With more than 5.5 million print volumes, 4 million e-books, 17 million digitized pages, 1,500 electronic databases and 320,000 full-text electronic journals, the UF libraries are the largest academic information resource system in Florida. More than 3.5 million faculty, students, staff and guests visit the libraries annually, and 4.5 million people visit the website.

Technological advancements have always been at the forefront of the libraries’ evolution. In 1966, UF was among the first institutions to collaborate with the Library of Congress on developing a computerized catalog information system. Consolidation of six smaller libraries into the Marston Science Library in 1987 reflected the increasingly interdisciplinary nature of research and was a forward-thinking decision for the time. The dawn of the digital era saw the inauguration of the Digital Library in 2000 and in 2019 UF began a mass digitization project with Google Books.

As digital tools have become more varied and complex, the libraries have kept pace. The Academic Research Consulting & Services, or ARCS, team provides unique expertise and services to support research activities using artificial intelligence tools and the university’s HiPerGator supercomputer, geographic information systems and data visualization, and other technologies.

“Our newest department, ARCS, aggregates a number of very talented faculty from a wide variety of disciplines, like informatics, data science and AI, who support many departments and colleges,” says Judith Russell, dean of University Libraries. “Much as the libraries support each unit on campus, ARCS does the same. This is an increasingly multidisciplinary team which reflects and responds to the collaborative nature of research.”

Over the last 15 years, UF researchers have documented large declines in oyster reefs in the Big Bend region of Florida. These declines, which likely began in the 1980s, have impacted not only the oyster populations, but also other parts of the coastal ecosystem which depend on oyster reefs for fish and wildlife habitat, and commercial harvest. Working with the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, a team of UF researchers secured funding to restore Lone Cabbage Reef, located at the mouth of the Suwannee River.

“We came to ARCS needing assistance tackling some really difficult design challenges with the project and also creating a modern data workflow to manage the data related to the oyster reef restoration,” says Bill Pine, a professor in the Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation who led the project. “ARCS was with us every step of the way, from helping to write our data management plans in the proposal, to completing the GIS work required for the design-build parts of the restoration, to tackling data on water quality and oyster projects throughout.”

GIS librarian Joe Aufmuth says, “Working on projects like the Lone Cabbage Reef restoration has shown me the power of interdisciplinary collaboration. By combining our expertise in GIS with the knowledge of environmental scientists, we can achieve remarkable outcomes.”

When Borui Zhang, UF’s inaugural AI librarian, first met Nicolas Gauthier, the Florida Museum’s first curator of artificial intelligence, they immediately saw opportunities to transform how people interact with museum and library collections.

“He specializes in image processing, while my expertise is in natural language processing,” Zhang says. “Both the library and museums have large ‘collections,’ but it can be difficult to find the right data.”

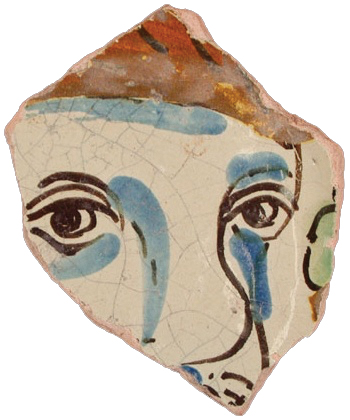

The two are exploring how advanced AI models can make vast museum and library collections more accessible. Their work combines computer vision and natural language processing to help people discover and explore artifacts using everyday language rather than technical terminology.

“The language models Borui works with make all this possible. They can adapt descriptions for different languages and knowledge levels, making our collections accessible to everyone from researchers to students to the public,” Gauthier says. “People can upload a picture, draw a sketch, or describe what they’re looking for — like ‘pottery with spiral patterns in blue’ — and have a conversation about what they find.”

“Integrating AI into our library services has opened up new possibilities for research and accessibility,” Zhang says. “It’s exciting to see how these technologies can transform the way we interact with and utilize our collections.”