Like most physicians, Dr. Carol Mathews keeps educational pamphlets in her office about the conditions she treats. Unlike most doctors, she doesn’t want patients to take them.

“I actually have to tell my patients, ‘You’re not allowed to pick up any flyers in my office. I’ll give you the one that’s relevant. You don’t need all the rest.’”

That’s because they’re seeing her for hoarding disorder, a chronic psychiatric condition marked by an inability to part with items that others might easily identify as unnecessary. It’s one thing to keep your late mother’s hairbrush, but most of us wouldn’t feel the need to keep the hair stuck in it. For Mathews’ patients, though, shedding items can feel like losing part of their identity. In the United States, the newly recognized disorder affects about 4% of adults, rising to 6% of those over 65. Found in every country researchers have studied — even minimalist Japan — hoarding is more prevalent than bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or obsessive-compulsive disorder, and is linked to falls, isolation, and 25% of deaths from house fires.

“It’s a hidden illness,” says Mathews, a UF Health psychiatrist. “Even people who have it don’t necessarily know it is a medical disorder.”

With support from the National Institutes of Health, Mathews and her collaborators are demystifying hoarding. They’re looking for genetic markers and big-data clues that could help spot the warning signs of a condition that intensifies with age, offering hope for patients, loved ones and caregivers.

Reality vs. reality TV

Christina, 33, glances at the stack of textbooks in her bedroom. She’s been holding onto them for years, and hasn’t needed them once. But what if she needed them in the future?

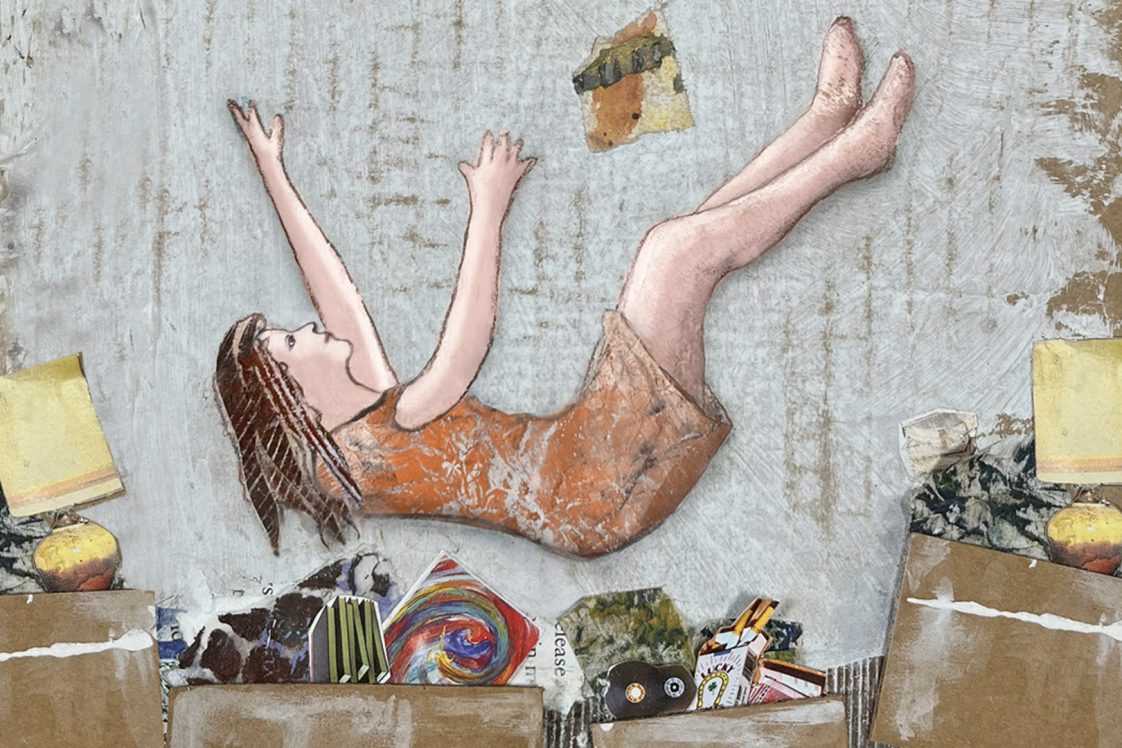

“I don’t know why I have them, but I can’t get rid of them,” she says. “Just thinking about it now, my chest is tightening up. I’m starting to get sweaty and anxious. So why even try? That’s why you end up drowning in stuff.”

For Christina, who is using only her first name because of the stigma surrounding the disorder, the symptoms intensified after her first daughter was born eight years ago. She got good at hiding the clutter, finding places to stash items she knew she no longer needed, but couldn’t part with. Still, the piles of papers and outgrown baby clothes were taking a toll on her marriage. She had seen reality shows where extreme hoarding cases grapple with eviction, shame, denial. She didn’t want that for herself or her family.

“Hands down, I could see where I would be on the show in another 30 years,” she says.

She turned to Mathews for help.

A fascination with the brain had led Mathews to medical school, where she planned to be a neurosurgeon, but quickly realized that path didn’t offer much opportunity to get to know her patients.

“Being very interested in how the brain works, psychiatry was a logical extension of that,” she says.

While studying OCD, Mathews noticed that her patients’ hoardings symptoms didn’t respond the way she expected. At the time, hoarding was considered part of OCD. After it was recognized as its own disorder in 2013, Mathews dove into understanding it. With $3.7 million from the NIH and more than $2 million from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Mathews and colleagues at the University of California San Francisco and Massachusetts General Hospital are working toward better diagnosis and treatment.

In an ongoing NIH-backed study, Mathews draws on local patients as well as the Brain Health Registry, an online repository of 54,000 volunteers who share assessment results every six months to aid in clinical trials of age-related disorders. Using symptom and diagnosis data from over 30,000 participants 60 and older, Mathews hopes to predict who may be vulnerable to hoarding later in life, helping patients and families affected by this highly heritable disease.

What qualifies as hoarding?

If you’ve read this far, you might be eyeing an overstuffed closet and wondering about your own tendencies, or thinking of a loved one who long ago gave up on fitting cars in their garage. While hoarding and its risk factors are still poorly understood, one thing is certain: it’s different from simply having too much stuff. It’s also different from collecting, which might look strange from the outside, but makes perfect sense to the collector.

Like Christina’s textbooks, the items people with problematic hoarding amass don’t bring them pleasure.

“It’s not a feeling of joy, the stuff I have,” she says. “It’s a feeling of obligation. What if I get rid of it and something bad happens?”

One question helps researchers determine when stuff is more than clutter: Are you unable or unwilling to let someone into your home? If so, there’s a better than 80% chance you have hoarding disorder, Mathews says. (Other predictive questions: Can you use your bed or kitchen table as intended, or are they partly covered in stuff?)

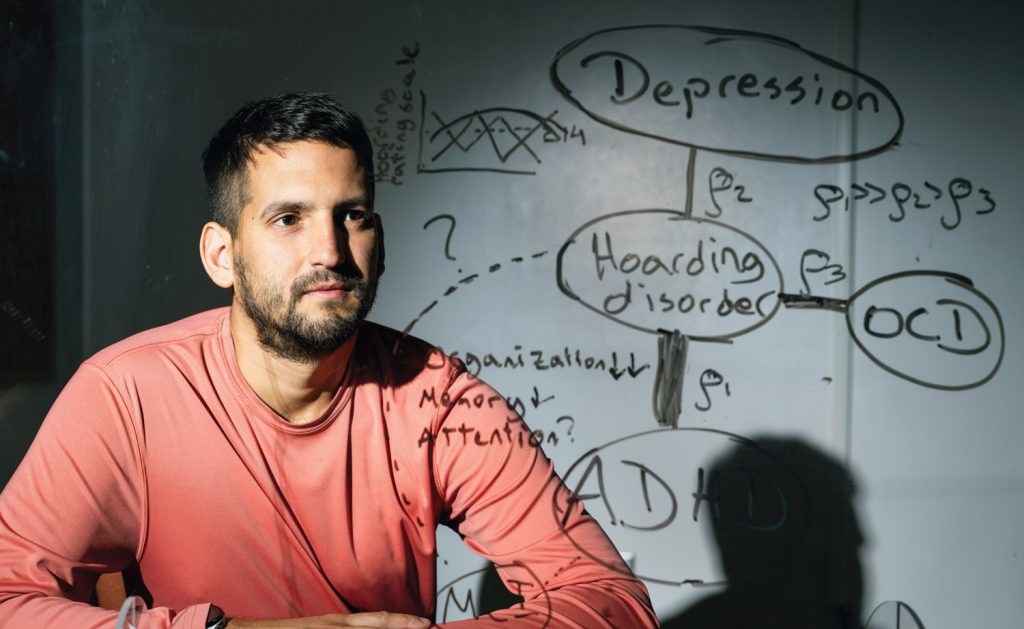

Because many don’t see their hoarding as a problem, much less a medical disorder, Mathews and her colleagues want to develop other ways to predict who’s at risk. For that, the researchers turned to math. As part of the NIH study, Luis Sordo Vieira, a UF computational biologist, used the university’s HiPerGator AI supercomputer to analyze data from the Brain Health Registry, which includes 24,000 responses to hoarding questionnaires alongside other longitudinal measures. Using network science, machine learning and artificial intelligence, Sordo Vieira hopes to find ways to screen patients and catch hoarding early, an approach that isn’t usually used because of the small sample sizes typical in psychiatric studies, he says.

“We know so little about mental health disorders and psychiatry as a whole, and yet we have all these large databases coming out,” Sordo Vieira says. “How do we best leverage them to better understand psychiatric disorders?”

Sordo Vieira’s research looks for connections that can help doctors predict who is at risk without asking about hoarding at all. That’s advantageous for three reasons: It avoids the stigma around hoarding; it doesn’t rely on patients or physicians knowing about hoarding as a medical disorder; and finally, it doesn’t add the burden of screening for yet another condition during the brief time doctors get with patients. Mathews and Sordo Vieira have already found correlations to depression and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Sordo Vieira hopes big data analysis could open new pathways in psychiatry for other disorders, too.

“What I’m trying to do is connect these different disorders that are usually thought of as silos,” he says. “These things don’t occur in isolation. Can you look at a patient’s symptoms as a whole and come up with individual therapies? That’s the idea I would like to push forward.”

Bringing hoarding out of hiding

A daughter stands in her widowed father’s living room, where clutter covers every available surface. After a complaint from a neighbor, he’s in danger of having his house condemned. She’s concerned, he’s unmoved. It’s a familiar scene to anyone with a loved one who hoards, but it’s playing out in the American Airlines Theatre with Danny DeVito.

DeVito and his real-life daughter Lucy co-starred in the Broadway play “I Need That,” which closed in December. Mathews didn’t see the play, but she’s intrigued: Could this be an indication that hoarding is moving out of the shadows? Because the disorder disproportionately affects older people, its prevalence will likely climb as the U.S. population ages. The nonprofit Population Research Bureau estimates that the number of Americans 65 and over will climb to 82 million by 2050, a 47% increase from 2022. Add in the millions of caregivers and loved ones affected, and the disorder suddenly seems like a public health issue, not a fringe fascination on reality TV.

For those wondering how to help a loved one, Mathews emphasizes that hoarding is treatable. Options include cognitive behavioral therapy where patients learn to discard items and a technique called motivational interviewing that builds buy-in for change. Mathews has also studied peer counseling by those with lived experience in hoarding, which she has shown can be just as effective as professional therapy. Another approach is harm reduction, which can help make homes safer for patients who aren’t ready to reduce their hoards.

Safe treatment, she is quick to add, never includes the type of forced clear-outs seen on television, which can put patients into crisis.

For Christina, seeing Mathews and other UF doctors has helped her understand that she can part with items without disregarding the meaning they once held. She used to keep all of the papers her daughters brought home from school — not just the adorable art projects, but every single math worksheet. She held onto all of their baby toys and clothes and blankets. To relinquish even one item would have felt like erasing part of their precious childhood. No longer.

“I’ve gotten rid of a ton of things now,” she says. “It’s a process. But it’s like weights that were holding me down are slowly being released. I’m finally able to breathe.”

Sources:

Carol Mathews, M.D.

Donald R. Dizney Chair and Professor of Psychiatry

carolmathews@ufl.edu

Luis Sordo Vieira, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor of Medicine

luis.sordovieira@medicine.ufl.edu