Growing up in the northern Italian town of Bolzano, near Italy’s border with German-speaking Austria, Eleonora Rossi regularly spoke Italian and German as a child. At 15, she began attending a high school specializing in foreign languages, adding English, French, Dutch and even some Latin to her repertoire.

She says she had so many languages being spoken to her that she came home one day holding her head and told her mother “my brain hurts.”

“In a couple of months, the professors would never speak any Italian to us. It was only the foreign languages,” Rossi says. “In the course of a school day, we maybe had two hours in French, two hours in English. It really did make my brain hurt.”

Today, Rossi, an assistant professor in the UF Department of Linguistics, understands that just as muscles hurt after an intense workout, her brain was exercising so many functions to process learning these four new languages that it became, well, sore.

“Nowadays, as a scientist in the field, I know exactly what was happening,” Rossi says. “There are massive activations your brain needs to do in order to pick up all that information and juggle the competition between all the languages.”

Neuroplasticity

While much of the brain’s development occurs in childhood and adolescence, Rossi says “it is clear that cognitive and neuro-flexibility really exist throughout the lifespan.”

Neuroplasticity or brain plasticity is how our brains adapt, change and respond to different environments.

Megan Nakamura, a UF doctoral candidate and 2019 National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow, describes the brain as a “ball of Play-Doh that’s always changing.”

Nakamura – who Rossi mentored as an undergraduate at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona – describes how every experience changes the brain and its plasticity. Language learning is a powerful one of those experiences.

“A lot of research shows prolonged bilingualism has a positive impact on the brain. There’s a few studies that indicate bilingual brains have an increase of gray matter, and more matter is more brain,” says Nakamura, a first-generation college student. “It keeps your brain healthier.”

In California, with funding from an NSF Partnership in Research and Education (PIRE) grant, Rossi and Nakamura collaborated with researchers at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands to compare how two different groups of native English speakers learned Dutch. Rossi worked with participants in California while Nakamura traveled more than 5,000 miles to the Netherlands.

There’s a few studies that indicate bilingual brains have an increase of gray matter, and more matter is more brain. It keeps your brain healthier.

Megan Nakamura

For 10 days, participants came into the respective labs to learn Dutch for an hour using the Rosetta Stone language software. The only difference between the two groups – the English speakers in the Netherlands were in a Dutch environment.

While both groups learned Dutch during the training, Rossi says, the results showed that the subjects in the Netherlands, immersed in the Dutch language and culture, learned faster and better.

Now, they’ve brought their research to the Department of Linguistics at the University of Florida to investigate how short-term new language training can shape linguistic, cognitive and neural measures in younger and in older adults.

BLaB

Within the maze of offices in the basement of Turlington Hall, in the heart of UF’s campus, is the Brain, Language and Bilingualism lab, affectionately known as BLaB.

It’s where Rossi, lab co-director and linguistics Associate Professor Edith Kaan and Nakamura are seeking to understand how learning another language changes the brain and what benefits, if any, it bestows.

Since arriving at UF in 2003, Kaan has pioneered psycholinguistics research and paved the way for the work of colleagues like Rossi. She is known for her work on language processing in monolinguals and second-language learners by looking at their brain waves.

Kaan says Rossi’s arrival created an opportunity for the two of them to combine their strengths to create BLaB.

“We are one happy family,” Kaan says. “We inspire each other every day. We identify ourselves as being a center for bilingualism.”

Rossi says UF is poised to become a national leader in this field.

“It seems to be one of these moments where there could be a big explosion of bilingualism research at UF,” she says.

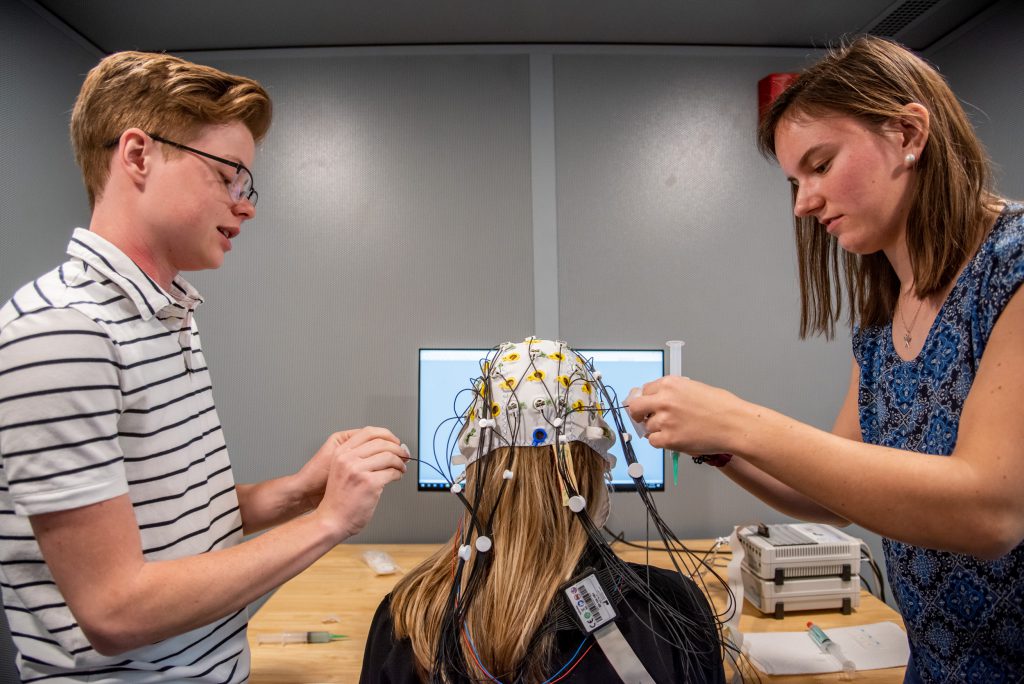

As part of her recruitment to UF, Rossi received funds to build BLaB, knowing she needed a specially outfitted lab to further her research. The lab is a soundproof room that looks more like a bank vault than a research facility. Inside are a chair and a desk and a computer monitor.

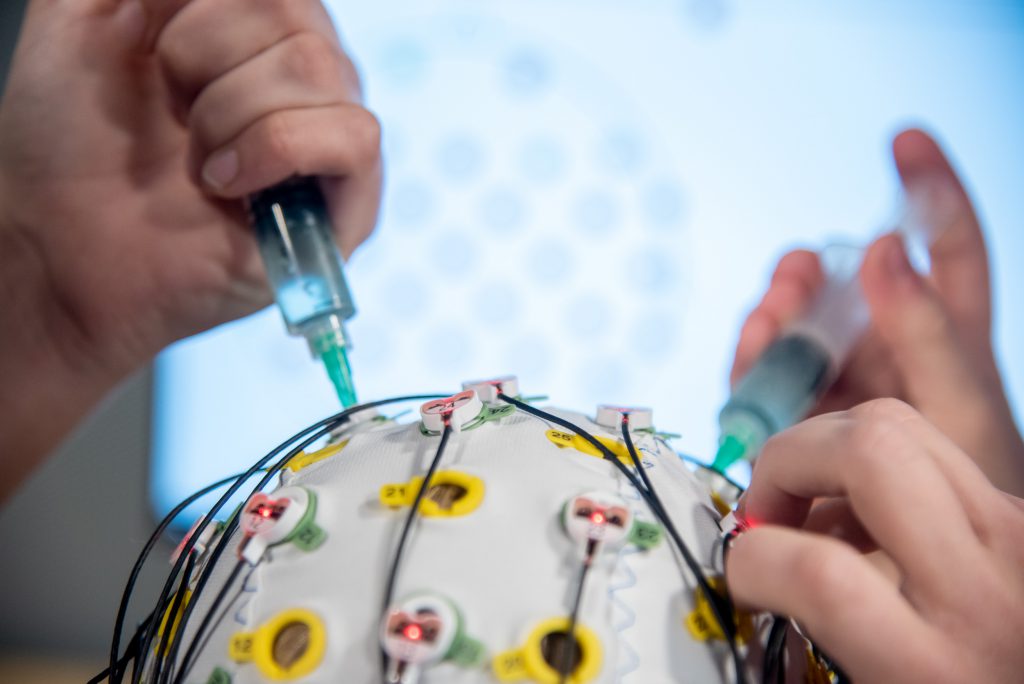

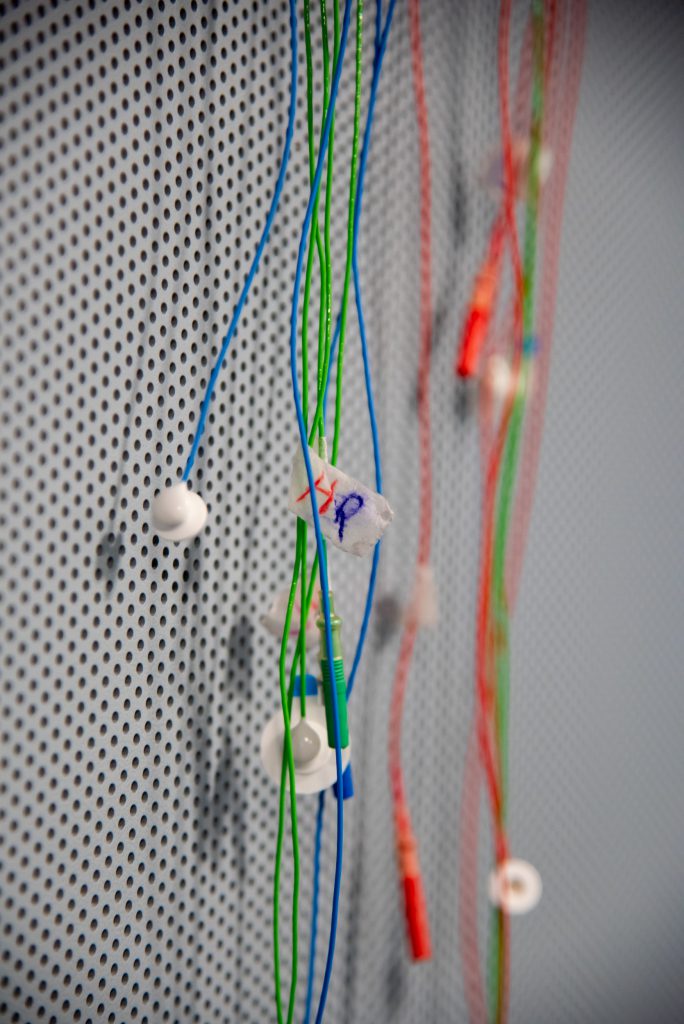

On the wall hang electroencephalography (EEG) caps, or what Rossi calls “funny swimming caps,” that are equipped with several dozen electrodes that allow the researchers to monitor subjects’ brain waves. Electrodes around the eyes ensure participants’ blinks or muscular twitches are also accounted for in the data.

Work in BLaB often extends beyond the Department of Linguistics, Kaan says. For example, Jorge Valdés Kroff, an assistant professor of Spanish and Portuguese studies, frequently works on projects with Rossi and Kaan. Three scholars from abroad have visited BLaB since it opened in mid 2019, and in January UF joined Cal Poly and Penn State University as a site for the NSF PIRE grant.

“I’m very proud of the cross-disciplinary environment and multiculturalism of our lab, partly because I am an international scholar,” Rossi admits. “I really believe in the value of embracing cultural diversity in our lab.”

Kaan believes BLaB’s culture provides an opportunity to attract Latinx and other minority students to the field.

“Bilingualism is part of Latinx students’ identity,” Kaan says. “It has been a major boost to draw minority students to conduct research as well.”

Several times a week, test subjects come to the lab, where they are fitted with the EEG caps and sealed in the lab, where they do a number of tasks to measure different aspects of language processing and learning. As the brain waves move up and down on the monitors, Rossi watches in real time how these waves change in response to language stimuli and how quickly brains adapt to things like learning a new language.

While the participants may be unaware they’re retaining a language after only two weeks, the brain data tell Rossi otherwise. “Our research shows our brains are much faster at encoding the information than what we think,” Rossi says.

“Our brains really outpace us. We should believe in our brains more.”

Great Debate

In the field of neurolinguistics, there is a continuing debate about whether people who speak more than one language have a “bilingual advantage” over monolingual speakers.

Rossi says that while the scientific literature is generally in agreement that bilingualism contributes to neural plasticity, or creates changes in brain matter across the lifespan, the debate lies in whether this results in behavioral changes.

Behavioral measures, such as changes in working memory or attention skills, are difficult to track, and they are measured differently across labs, Rossi says. Some labs find changes in cognitive functions in bilinguals; others do not. These different results have sparked a debate about how to appropriately measure cognitive functions and the accuracy of the results.

For Nakamura, bilingual doesn’t necessarily mean better.

“The idea of this lab is to never draw lines between monolingual or bilingual,” Nakamura says. “The idea is to show here’s what and how the brain changes if you are not bilingual or you want to become bilingual.”

Nakamura is currently recruiting participants for a three-year project to investigate bilingualism in both young adults and the elderly. By studying the brain waves of young and older monolinguals and bilinguals, she aims to understand how the brain responds to learning a third, new language for those who have lived life being bilingual versus those who have not.

“There’s only a handful of people doing this and asking these questions,” Nakamura says. “This NSF Graduate Research Fellowship makes it possible for me to dedicate all my time to be in this lab.”

Bilingual World

As Japanese natives living in Hawaii before World War II, Nakamura’s grandparents and great-grandparents spoke both Japanese and English. But after the attack on Pearl Harbor, her great-grandparents stopped speaking Japanese and told their children to speak only English.

Nakamura, whose Mexican mother raised her to speak Spanish, wishes her grandparents, who now only remember a few phrases in Japanese, hadn’t lost their native language.

“The war took away a big chunk of people who could have been Japanese–English bilinguals,” she says. “It took that away for me. You don’t really realize how much bilingualism has an impact on societal culture until you sit down and think about it.”

Today, she hopes her work will enable the world to embrace culture differences and destigmatize the idea that bilingualism is foreign.

“No language precedes another,” Nakamura says. “The work we do in this lab can easily be translated into this broader aspect that people shouldn’t fear bilingualism.”

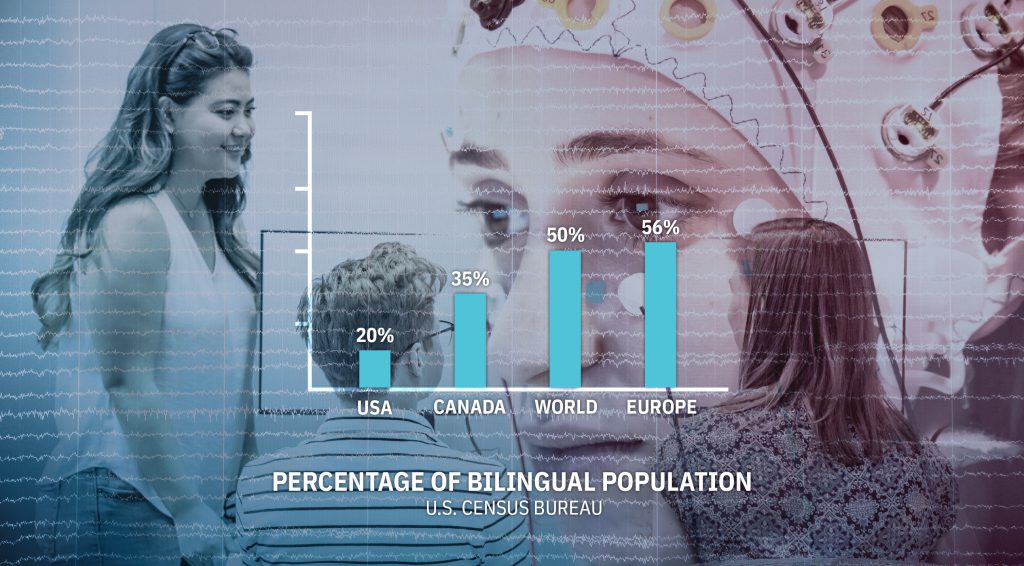

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, only 20 percent of Americans can converse in two or more languages, compared with 56 percent of Europeans, and some experts estimate about half of the human race speaks at least two languages.

Because of her personal experience and her research, Rossi is a strong advocate for language education.

At the American Association for the Advancement of Science meeting in February, Rossi presented a talk about how societies can benefit from embracing bilingualism. She firmly believes bilingualism contributes to a society’s health, education, culture and economics, and she’s gathering data to back that assertion.

“Bilingualism can open a door to communication with neighbors, further job opportunities and aid in healthy aging,” says Rossi, who would also like to see language education promoted in K-12 schools. “What is the negative value of teaching Spanish to our English kids? There is no bad value.”

Sources:

- Eleonora Rossi, Assistant Professor of Linguistics

- Edith Kaan, Associate Professor of Linguistics

Related websites: