Like so much of science, the invention of Gatorade 50 years ago seems to have happened by magic, as if the whole story could be told in a 90-second television commercial narrated by Keith Jackson.

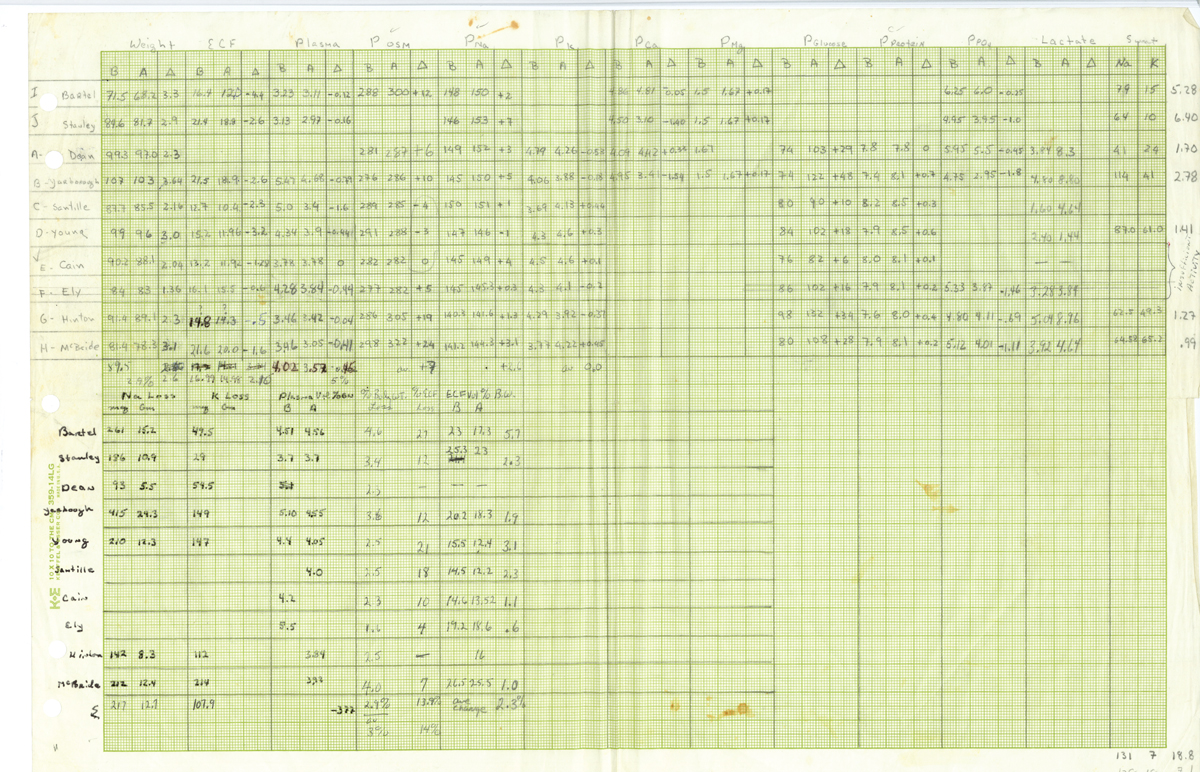

But a closer look at the copious amounts of data Dr. Robert Cade and his colleagues recorded by hand as they sought to understand the physiological changes Gator football players were experiencing in the hot, humid Florida summer reveals the science behind the magic.

In small, concise script across yellow ledger paper, the researchers recorded ambient temperature and humidity, sodium and glucose levels, plasma and potassium volume, and times in the mile and 880-yard run.

The results were eye-opening. The players’ electrolytes were completely out of balance, their blood sugar was low and their total blood volume was low.

The impact on the body of this upheaval in chemistry was profound.

“Each of these conditions, by itself, would to some extent incapacitate a player,” Cade said. “Put them all together and you can have real problems.”

With hard data in hand, Cade’s team began pursuing a remedy.

“The solution,” Cade said, “was to give them water, but with salt in it to replace the salt they were losing in sweat. Also, give them sugar to keep their blood sugar up, but not so much sugar that it would upset their stomachs.”

By all accounts, the first batch tasted so bad none of the scientists could stomach it, but when Cade’s wife, Mary, suggested adding lemon juice, the drink that would soon become known as Gatorade was born.

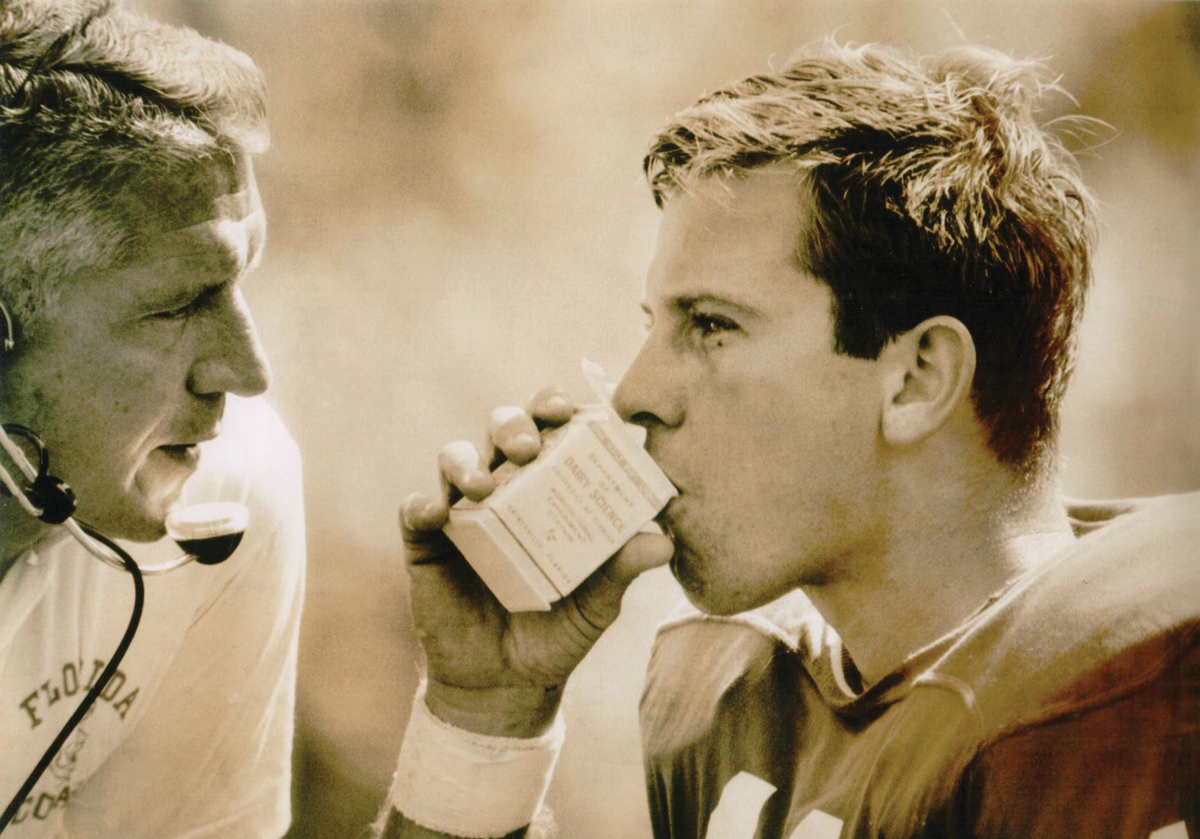

The Gators saw the results on the field immediately, often coming from behind to win games, and in time so did athletes on other teams and in other sports.

Oversized Impact

University of Florida faculty have been conducting scientific experiments since the university’s earliest days — in agriculture, engineering, medicine and many other fields — but the experiments Cade’s team conducted in 1965 have had an oversized impact on the university in the intervening half century.

The more than $250 million in royalties Gatorade has brought to the university have helped to fund thousands of research projects, often providing seed money to faculty who were then able to leverage it into millions more in grants from public and private agencies.

Indeed, many of the UF faculty who brought a record $702 million in research awards to the university last year have benefitted from Gatorade support.

“These funds have allowed us to be competitive with some of the top schools in the country in terms of preparing ourselves with infrastructure, making strategic investments and recruiting high-end researchers in a way that would not have occurred otherwise,” says UF Vice President for Research David Norton.

Gatorade’s success has also inspired generations of scientists to think about how their discoveries could be transferred to the marketplace.

UF entomologist Nan-Yao Su credits Cade for providing him with the inspiration to pursue a new treatment for termites that became the Sentricon Termite Colony Elimination System. Since its introduction in 1995, Sentricon has protected millions of buildings and generated more than $40 million in royalties.

“Gatorade and Sentricon are sort of linked together now, not just because they were both invented at UF and were very successful products, but because Dr. Cade inspired a lot of people, including myself,” Su says.

Gatorade also inspired university leaders to pursue technology transfer aggressively and today UF is consistently ranked among the top institutions in the world at moving discoveries into the marketplace.

“We had a head start on much of the community because of Gatorade and what that invention meant to us,” Norton says.

Over the past 12 years UF has launched more than 160 biomedical and technology startups. According to the Association of University Technology Managers, in 2013 UF ranked sixth in the nation with 16 startups launched and eighth for US patents issued with 107.

Gatorade has also helped to support UF’s two business incubators. The Florida Innovation Hub at UF has contributed to the creation of hundreds of jobs in just its first four years and the Sid Martin Biotechnology Incubator was recently ranked “World’s Best University Biotechnology Incubator,” based on an extensive analysis of 150 incubators in 22 countries.

“We’re moving the cutting-edge research generated at the university from the laboratory to the market, where it helps people in their daily lives,” Norton says. “Outside the lab, these inventions can make the world a better place.”

This article was originally featured in the Summer 2015 issue of Explore Magazine.