“All across the nation

Such a strange vibration,

People in motion,

There’s a whole generation

With a new explanation . . .”

— San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair), Scott McKenzie, 1967

The flower children drawn to San Francisco in 1967 by the strains of Scott McKenzie’s song took to the streets of Haight-Ashbury with youthful abandon in a counter culture celebration, the Summer of Love.

A half century later, the turn on, tune in, drop out generation finds itself on a different march — into retirement — touching off a revolution in what it means to get old in America, says University of Florida Professor Stephen Golant.

Commemorating the 50-year anniversary of the Summer of Love for the journal Generations, Golant says if the hippies had had a crystal ball to show them how much their own old age would differ from their grandparents’ old age they might have been waving signs with different slogans, perhaps “love your elders” or “no more nursing homes.”

Just as the Baby Boom joins the Greatest Generation and Silent Generation in old age, society is becoming reluctant to describe anyone as old, as if “old” is a bad word, Golant says.

“The attitude toward aging has changed over the course of my career. We are much more sensitive about ageist practices and behaviors,” Golant says. “But there is a tremendous emphasis to want to deny aging as a stage of life.”

Since the late 1980s, the concept of successful aging has preached that you don’t have to get old if you exercise, eat right, get enough sleep, stay active, have a hobby. On the heels of that philosophy came the “aging in place” model, urging older Americans to stay in their homes as long as possible.

These messages, Golant suspected, were not one-size-fits-all prescriptions for older Americans. The generation that gave birth to celebrations of diversity following the social upheaval of the 1960s would not suddenly become a homogenous population living together in harmony in old age.

Instead, the baby boomers, Golant says, are “redefining the conception of getting old.”

And where the new generation of older Americans chooses to live, he thinks, could be a key to successful aging.

Aging in the Right Place

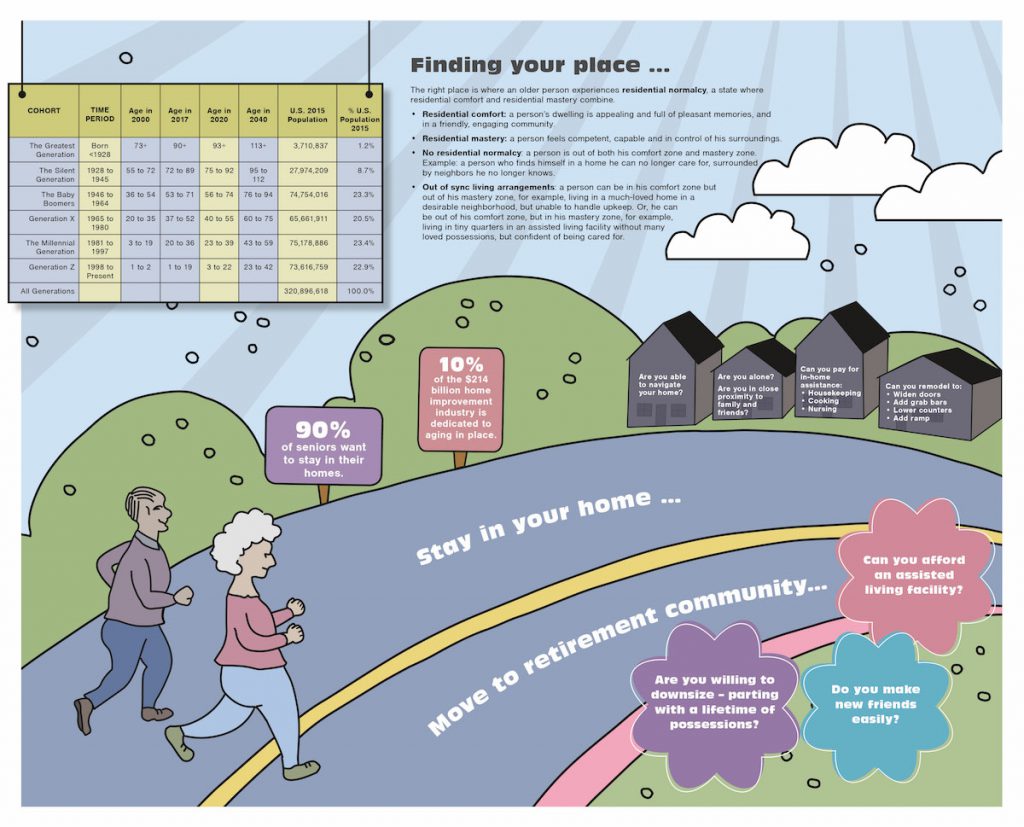

For the next decade or more, 10,000 people a day in the United States will reach the age of 65, as the 63 million late middle age boomers — ages 50-64 — join the 16 million older boomers who make up a third of today’s population 65 and older.

With his interdisciplinary view as both gerontologist and geographer, Golant says one decision can affect the success of all the other decisions you make about aging: where you live.

For all their youthful rebellion, a huge portion of the love-in, sit-in set have ended up in the cul de sacs of suburbia, and their low-density living can be an impediment to accessing everything from groceries to doctors if they do not have auto transportation, Golant writes in his recent book, Aging in the Right Place.

A longtime family home can be a good choice — or not — but it is not the only option. Others span a continuum ranging from living in luxurious assisted-living communities that offer a suite of services from health care to housekeeping, to modest age-restricted communities or with family members. In between are various downsizing options offering varying levels of independence.

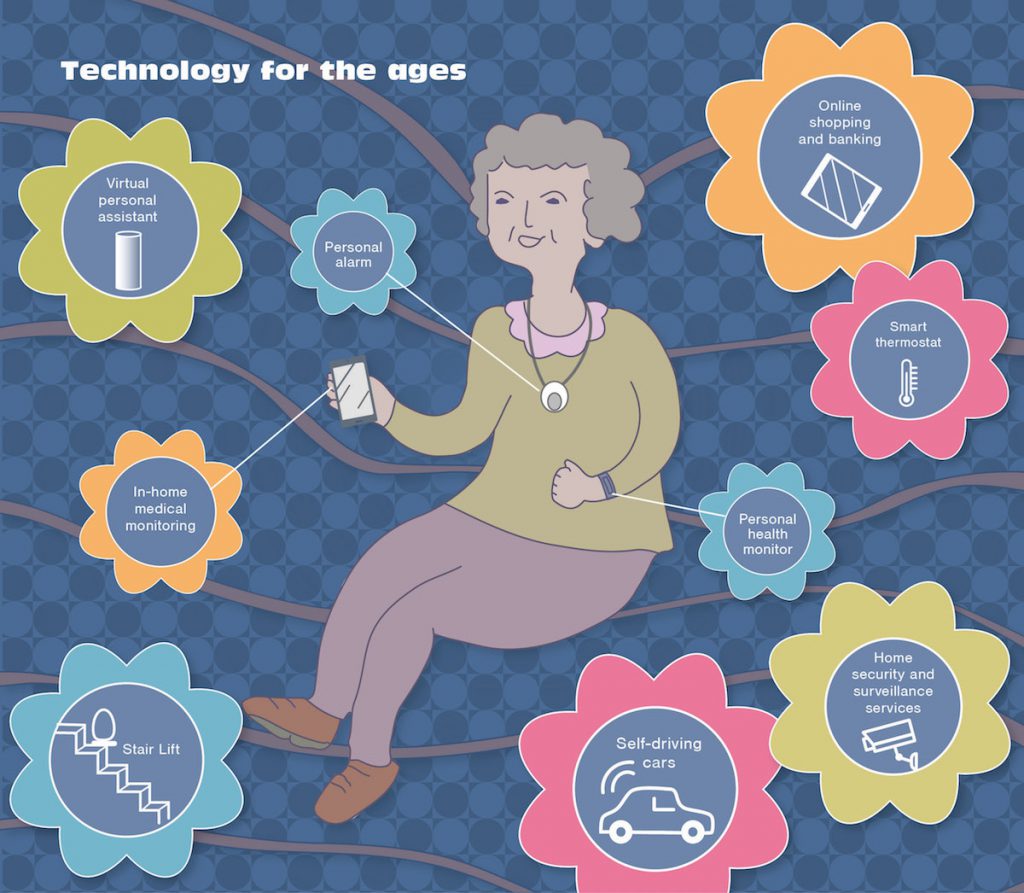

And another revolution in society — the technological revolution — may be the most critical factor in living independently in old age, Golant says.

In 2015, 58 percent of persons age 65 and older used the internet, compared with 14 percent in 2000. In the 1970s about 6 million older people lacked even a telephone. The change in connectedness in the last half century is allowing older generations to shop, bank and manage their finances online. They are able to access information about medicine and health care and order medications online that are delivered to their door.

Self-driving cars could make the loss of a driver’s license a less traumatic event, as could services such as Uber. Barriers to navigating the physical environment in public have declined since the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990. Virtual personal assistants, such as Amazon’s Alexa, can be instructed by voice to do a range of tasks.

“Once upon a time, there was a concern that older people who had to get their checks cashed were susceptible to being ripped off,” Golant says. “That threat is in many ways reduced.

“Gerontechnology — smart homes, telehealth and telemedicine — will allow baby boomers to track their physiological functions, health status, mobility, dwelling functions, and physical and social activities from the comfort of their homes,” Golant says. “Wireless sensors inserted in their bodies and clothing, and on the walls, floors, ceilings, furniture and appliances will transmit information to remote monitoring stations. When sensors detect deviations from norms, they can trigger interventions by family or others.”

The up side is that older Americans may rarely need to leave their homes. But that also is the down side, Golant says. Aging in place may be lonely, isolated from everyday human connections with grocery baggers or bank tellers or postal clerks.

Residential Normalcy

The grandparents of the baby boomers were likely to live out life in a nursing home if their health failed, or at home with family. Golant says most people have an inflated idea of nursing home residency today. The nursing home population has fallen from 6 percent of older people in the 1970s to 2.5 percent today, a particularly startling statistic considering that the oldest populations today are in their 80s and 90s and that cohort is rapidly expanding.

Just as the hippies of the 1960s have exhibited an independent streak in their approach to aging, so have women. In 1970, only 42 percent of women 60-69 were licensed to drive. By 2014, 89 percent of women in that age group held a driver’s license and all the independence that goes with mobility. That will change the traditions of caregiving, Golant says.

“Daughters or daughters-in-law have been the default caregivers for our elders in the past,” Golant says, “but women have changed.

“We’re in a generation of women used to having jobs and having independence and sending their 18-month-old to child care,” Golant says. “If you’re willing to send your 18-month-old baby to child care, what is to say you wouldn’t be willing to have your mother or father in elder care? So, the idea of the daughter as the caregiver is changing, absolutely.”

If family care is not an option, older Americans who opt to age in place will need to make peace with hired, in-home care, Golant says. While a 65-year-old in 2006 could expect another 12.2 years of active life, he had 6.3 years after that of dependent life.

In his book, Golant offers a theory of residential normalcy, the ideal situation in which older people feel comfortable, competent, and in control of their lives. When residential normalcy is achieved, a person is aging in the right place.

Often, the quest to age in place, however, leads to a living situation in which a person is no longer comfortable or competent. A longtime home may be too big, exhausting, or too expensive to maintain. Interestingly, Golant says, the same person so eager to follow a job opportunity or relocate for a lifestyle change at 30 often does not recognize the need to relocate due to the changing circumstances of aging, even when a move would make him more comfortable and self-reliant. Residential inertia sets in, and only about 2 percent of older homeowners and 12 percent of older renters move annually.

Many people also are reluctant to part with their home, their most valuable investment.

“The house is viewed as a last resort source of money,” Golant says. “If you run out of money, you can sell the house and get your heart transplant and move in with your son and daughter-in-law.”

Alternatively, the home can be left as an inheritance.

Golant says it’s no surprise to find the older boomers are much more connected than their grandparents were, and the connections have boosted their well-being. They face the final stages of life better off in many ways than generations before. Golant hesitates even as he makes the statement. He worries that policy makers will target the very programs that have made a better life possible for aging Americans.

“Are older people better off? Absolutely. But it’s because of those programs like Social Security and Medicare.”

Even older Americans who appear to be relatively well off are often one or two calamities away from financial stress: a leaking roof, a heating system gone bad. Golant says the middle class is most at risk. The rich can achieve their aging in place preferences or access top-notch facilities. The very poor will get at least some federal assistance to cover their care expenses. The middle class will not be able to afford the nicest retirement and care options and will be ineligible for government programs.

“A downside to underplaying old age, not celebrating old age, is that you don’t prepare for old age,” Golant says. “You don’t see it coming.

“We respect reaching adolescence or young adulthood or middle age,” Golant says. “I want to respect old age.”

Aging well is important, but so is accepting the eventual arrival of old age. All generations, after all, get old.

Photo Credits: John Jernigan

Source:

- Stephen Golant, Professor of Geography

Related Website:

This article was originally featured in the Fall 2017 issue of Explore Magazine.