In patients with leukemia, cancer cells can embed within the walls of blood vessels and hide from chemotherapy, according to a University of Florida study.

Now, researchers are using a two-year, $800,000 grant from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society to screen for new drugs that disrupt the tight-knit relationship between leukemia cells and blood vessels.

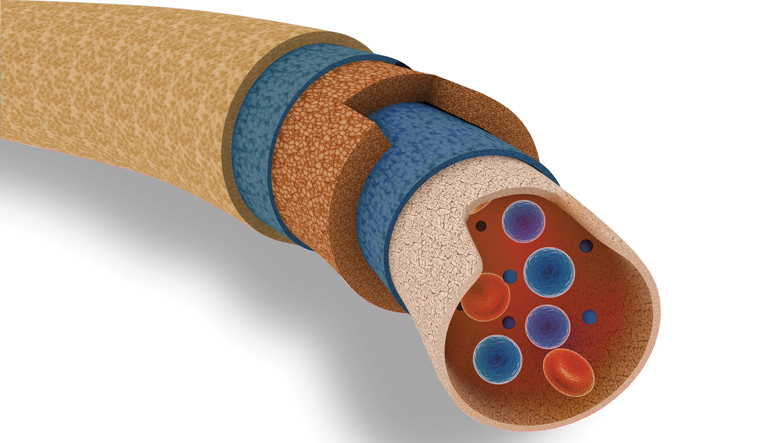

Dr. Christopher R. Cogle, one of the study’s lead co-authors and an associate professor of medicine at the UF College of Medicine, has found that leukemia cells hug the branches of blood vessels. When they do this, they integrate into the lining of the blood vessels. They also change shape, mimicking the long, thin cells lining blood vessels, called endothelial cells.

“There’s a protective advantage when leukemia cells integrate within blood vessels,” Cogle said. “The blood vessel walls are a shelter for leukemia cells, and we found that leukemia cells can nestle within blood vessel linings and go to sleep.”

This can cause traditional chemotherapy to wash over leukemia cells. After some time has passed, these hidden cells reawaken as a form of relapse, Cogle said. Relapsing leukemia is one of the greatest challenges in treating patients with blood cancers.

In the leukemia study, the researchers discovered leukemia cells clustering around and within blood vessel walls. Some leukemia cells fused with endothelial cells, blurring the lines between what is a blood vessel and what is cancer, said Ed Scott, a professor in the UF College of Medicine Department of molecular genetics and microbiology. Using a mouse model, Scott and Cogle, both members of the UF Health Cancer Center, were able to study human leukemia cells in mice. After treating the mice with chemotherapy, the researchers were able to study why some of the leukemia cells were able to survive, Scott said.

“A small number of these leukemia cells stuck to the blood vessels so tightly that we had a hard time getting them out of the blood vessel wall,” Scott said.

Cogle thinks these leukemia cells are responsible for relapsing disease.

“In the race of survival of the fittest, leukemia cells that hug blood vessels have a greater chance of withstanding chemotherapy and taking over the body,” Cogle said.

Most chemotherapies target rapidly dividing cells, which is why people lose hair and can become nauseated, Scott said.

“But when leukemia cells are in the blood vessel walls, it’s easy for them to get nutrients, hang out there and more or less take a nap,” Scott said. “If we can get them unattached or prevent interaction to begin with, then they are out in circulation where they are more exposed to chemotherapy.”

Cogle is currently testing a drug, called OXi4503, in patients with acute myeloid leukemia or a myelodysplastic syndrome to determine the safety of various doses. The drug appears to target blood vessels and leukemia cells. The phase one clinical trial started in 2011.

Sixteen patients age 18 to 70 have received the drug so far, and the team expects 12 more patients to receive it before the end of the trial’s phase one.

“We’re currently recruiting patients with leukemia to our trial,” Cogle said. “I work with an amazing team of laboratory and clinical researchers.”

Sources:

- Christopher Cogle, christopher.cogle@medicine.ufl.edu

- Ed Scott, escott@ufl.edu