Brent Sellers never tires of visitors’ reaction when he gives them a tour of the DeLuca Preserve, a 27,000-acre gem donated to the University of Florida in 2020.

His four-wheel drive Silverado 2500 is like a time machine as he opens a gate and steers it straight into the past, into a Florida known today mostly in history book pictures. It’s wild and unpopulated, not the Florida most people see every day, and he is used to open-mouthed stares and oohs and aahs.

As overseer of the preserve, Sellers is keenly aware of how easily his truck could have been a golf cart and the dirt road a four-lane highway. The gift from Elisabeth DeLuca, however, changed that fate, and Sellers and a growing cadre of scientists are grateful.

“The opportunities for research here are just about endless,” says Sellers, who added oversight of the preserve to his already big job as the director of the Range Cattle Research and Education Center, a 2,840-acre research ranch in Ona.

Sellers stops the truck for a moment at his favorite spot, where palmettos stretch across a landscape with soldier-straight pines lined up on a horizon of bright blue sky. Traffic on this day is a flock of dozens of wild turkeys with somewhere else to be and a cow and calf that refuse to budge from a patch of grass between the ruts of the road.

The road, however, is about to get busy.

To get science off the ground at the DeLuca Preserve, UF’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences earmarked $600,000 for Jumpstart Awards that funded eight projects involving 23 scientists. And although the preserve looks like a 1950s postcard, there is nothing dated about the science about to be unleashed on the sprawling ecosystem.

The first question for the science pioneers is a basic one: What’s there?

“We don’t have much information about the preserve from a foundational point of view,” says forest resource economist Andres Susaeta. “What we’re doing, what all the jumpstart awards are doing, is the first research to determine what’s in there.”

Assessing Biodiversity

Considering the rate at which the world is losing species, entomologist Lawrence Reeves wanted to try a faster way to measure biodiversity.

Traditional field work can take a long time, says Reeves, noting a project at the Savannah River Site in South Carolina where it took 45 years to accumulate enough records to identify hotspots of herpetological diversity. Science, he says, needs to move faster.

One novel way to speed things up is to use mosquitoes, a plentiful and untapped resource in Florida’s wildlands.

Reeves and his team will test whether analyzing DNA from mosquito blood meals is an effective way to determine the diversity of mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians, including threatened or endangered species.

“For a century, we’ve been interested in identifying the blood meals of mosquitoes in order to learn which animals they feed on from an epidemiological context, how mosquitoes act as vectors for viruses,” says Reeves, whose lab is at the Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory in Vero Beach.

“So, we’ve done a lot with mosquito blood meal analysis, but this will be among the first times it’s been applied to these kinds of questions about what vertebrate species occur in a particular area,” Reeves says. “It’s the first real in-depth test.”

Traditional methods of biodiversity surveys, like camera traps and acoustic monitoring, will also be deployed, and over time the approaches will be compared to see which is more accurate.

Mosquitoes can go places camera traps can’t reach and detect animals camera traps can’t, so analyzing blood meals could detect the presence of creatures from the smallest lizards to the largest mammals, potentially even Florida panthers if they’re out there.

To collect the mosquitoes, Reeves will use two methods. For one, he will wear a Ghostbusters-style aspirator attached to a backpack and move through the habitat, vacuuming mosquitoes out of their resting sites as he goes. For the other, he will set out resting shelters, which look like a trash can on its side, to attract mosquitoes looking for a dark, cool place to relax and digest after a blood meal.

“Mosquitoes go in thinking it’s a nice place to rest, and then we come along and vacuum them out.”

DNA is extracted from the blood, then PCR tests are performed, and DNA is sequenced. Those sequences are then matched to a database of sequences from different animal species.

Reeves said he realized the preserve’s potential for biodiversity work right away.

“On our first scouting trip to the DeLuca Preserve, we got out of the car and almost stepped on carnivorous hooded pitcher plants and sundews,” Reeves says. “We looked up, and there were crested caracaras flying overhead — it was like a scene straight out of the Pleistocene.”

Bottom Up

In conducting a ground-to-treetop assessment, Jango Bhadha, like the seasoned soil scientist he is, figured it made sense to start on the ground, characterizing the soil-water-microbiome domains at DeLuca.

To sense the magnitude of the job ahead, the team met at the preserve, with Bhadha driving up from the Everglades Research and Education Center and others coming from the Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center and from Gainesville.

“All of us have done ecosystems work, and scaling up is something we do on a regular basis,” Bhadha says. “But sometimes even though you might deal with hundreds and thousands of acres, the diversity could be monotonous, just one soil type or a single vegetation.

“The preserve has shrubs, flatwoods, wetlands, pines, palmettos. And then there is cattle and some old citrus groves,” Bhadha says. “It was 27,000 acres with all this diversity.

“So, it’s like a little kid in a candy store with all these different candies, and now I get to taste a lot of them all in one go.”

Bhadha will set up sentinel plots and analyze them for pH, organic matter, active carbon and other soil health indicators, as well as document land uses and the plant communities in various soils. Microbial diversity will be monitored along with seasonal wet and dry trends. Data will reside in a digital repository, open not only to researchers but to extension and K-12 classes.

“Open access data is key to leveraging the opportunities of the DeLuca Preserve for the benefit of all,” Bhadha says. “It is very important to get baseline data when the page is clear, to reflect the beginning. What we learn can then be used by others.”

Bhadha says he looked over the projects by fellow jumpstart awardees and noticed some synergies. He reached out to Aditya Singh in agricultural and biological engineering, who is assessing the tree canopies.

“We are doing everything below ground, they are doing the canopy,” Bhadha says. “Maybe we can find correlations.”

Singh’s team will use a small plane to deploy hyperspectral imaging equipment and LiDAR laser rangefinding to sample the entire preserve at high resolution, filling a vital early need to map and inventory the diversity across scales: biological, structural, functional.

Hyperspectral data will be collected on the ground as well. The data from the ground and airborne equipment will be curated, and then the team will deploy AI models to generate comprehensive maps of the plants’ biochemistry.

Singh says the curated dataset will be the first of its kind anywhere. The DeLuca Preserve, he says, is an ideal place to gather information to develop novel AI-based data integration algorithms.

Singh says the map and inventory will show the distribution and structure of plant communities, including rare and endangered species as well as invasive species. The team also will produce a photographic field guide handbook.

Future teams can use the data as a springboard. Want to look at mature stands of pine? Here they are. Need to study invasives? They’re over there.

Forests and Trees

Working forests — those managed for timber as well as for carbon sequestration, water production and aesthetics — dominate the southern landscape. Working forests:

• Have the potential to sequester nearly ¼ of the region’s greenhouse gas emissions

• Produce 34 percent of the water yield in the southern United States

• Host more than 1,000 native terrestrial vertebrate species

• Generate about $14 (water, carbon, habitat services) for every $1 in timber value

Andres Susaeta’s team wants to develop a bioeconomic model southern forest managers can use to assess wildfire risks and determine the tradeoffs of managing forests for timber production vs. ecosystem services.

Susaeta will establish 34 plots in the preserve, which will be examined top to bottom as data is collected. With 5,339 acres of longleaf, slash pine, sand pine, live oaks and understory species, the preserve is ideal for this work, he says.

To assess the canopy size and density, a Jetsons-style machine, a terrestrial laser scanner, will produce a 3D point cloud that can measure the volume of each and every tree, an important statistic considering that 50 percent of the volume of a tree is carbon.

The model could also help forest managers assess vulnerability to wildfire.

“Wildfire is a negative, but a prescribed fire is a tool,” Susaeta says. “Wildfire is something that we need to learn to live with, especially since the risk has increased because of climate change.”

Forest management practices can help or harm ecological functions, and variations in management from plot to plot matter. Stand A will be affected by how Stand B is managed, so the goal is to model those effects and share the information on an open database.

Susaeta says the plots can be permanent, so future researchers and grad students can use the coordinates to return for new experiments.

“This lab belongs to UF; it’s a fantastic natural laboratory for everything. After 20 years of measuring, we can see the evolution of the forest over time,” Susaeta says. “Think of the dissertations that will come out of there.”

Hidden Diversity

One of the most understudied aspects of biodiversity worldwide is fungi, yet no ecosystem could function without them, say plant pathologists Matthew Smith and Laurel Kaminsky.

Fungi help turn dead branches and tree trunks into soil and play key roles in carbon and nutrient cycling. Without fungi, dead wood would pile up and become tinder for catastrophic fires. There are an estimated 2.2 million to 3.8 million species of fungi on Earth but only 120,000 have been described. By comparison, of 300,000 plant species, nearly all are described.

In the past 10 years, Smith’s lab has found a handful of Florida fungi that had rarely been seen since they were originally described in the 1940s, along with a handful totally new to science. He and Kaminsky see DeLuca as fertile ground for new species since only 138 fungi collection records exist for Osceola County, most collected before 1980.

But that doesn’t mean fungi aren’t there. On their scouting trip, Kaminsky says, they were glad they brought their collecting gear because they found a bounty of fungi in minutes just a short distance from the entrance.

Smith and Kaminsky will collect, identify, document, preserve and DNA barcode the macrofungi at the preserve, and they hypothesize that DeLuca will yield rare fungi that are new to science or restricted to the region. The monthly collecting trips will be augmented by two mycoblitzes in which teams including students will collect as many fungi as possible. The specimens will be housed at the UF Fungarium, which Smith curates.

Basic questions scientists are starting to answer about other organisms — how climate change might affect distribution, for instance — can’t be easily answered for fungi yet, Smith says.

“We have all sorts of questions we would like to answer, but we don’t even know what fungi exist to begin with,” Smith says.

“In the DeLuca Preserve, there could be hundreds and hundreds unknown before now.”

DNA sequencing has also disrupted previous ideas about fungi. Smith and Kaminsky have uploaded DNA data from specimens they collected that should be one thing based on appearance but that turn out to be something else when DNA is sequenced.

“Once you start generating data, you find all kinds of hidden diversity,” Smith says. “Even under the microscope, we often can’t see differences.”

Smith says the preserve can escape the fate of Miami, where there were many early records of fungi from live oak hammocks lost to development.

The DeLuca Preserve, he says, represents an opportunity to collect in a habitat that has some features in common with the lost South Florida landscape.

“We can go in and see if some of those fungi might be there,” Smith says. “To get answers, we need to do this basic, age of discovery work.”

Sight and Sound

Wildlife ecologists Hance Ellington and Marcus Lashley are collaborating on two jumpstart projects.

Ellington, the wildlife specialist at Ona, is examining the influence of grazing on bird biodiversity, an important issue in Central and South Florida, where sprawling ranches contribute to open spaces used by wildlife.

Ellington will deploy 48 acoustic recording units to remotely monitor avian biodiversity across different pasture types grazed at different intensities. Grassland bird populations have been declining globally, and while pastureland may be more bird friendly than urbanization, there hasn’t been a lot of research to determine how grazing management impacts avian biodiversity.

Some avian species do well on pastures, others not so well, Ellington says. An improved pasture, for instance, generally is not burned, and the grasses are usually monoculture with uniform vegetation height. In contrast, DeLuca is a mosaic with both improved pasture and semi-native rangeland.

Ellington is also collaborating with research biologist Reed Bowman of Archbold Biological Station in work at DeLuca on the endangered grasshopper sparrow.

Lashley will be adding the DeLuca Preserve to SNAPSHOT USA, a standardized yearly camera trap survey of wildlife populations in all 50 states. SNAPSHOT USA has collected data three years in a row, so it’s the beginning of a long-term, open-access database. Some species, Lashley says, are monitored across their entire range.

“It’s unprecedented to be monitoring wildlife at that scale,” Lashley says.

At DeLuca, the work will create a record of diversity for the southeastern fox squirrel, the wild turkey, and non-native species like wild pigs. Ellington says he hopes to pair some of his 48 acoustic monitors with 60 camera traps where possible.

The preserve also puts time on a scientist’s side. As a dedicated research space, it allows scientists to start a 10- or 20-year project and be assured they can see it through.

“Frankly, in ecology,” Lashley says, “many things need to be studied for decades before you really start to get a good handle on how they work.”

Reviving Citrus

Citrus researcher Jude Grosser remembers being a graduate student in Kentucky and driving to a biotechnology meeting in Miami in 1983.

“We came down US 27, and it was just wall to wall beautiful, dark green, big, lush citrus trees as far as the eye could see,” says Grosser, who returned in 1984 to take a job at the Citrus Research and Education Center in Lake Alfred.

“When I drove back for my job, it looked like a nuclear bomb had gone off. All these skeletons of trees.”

That was the aftermath of the freeze of 1983. Today, the enemy is citrus greening, also known as Huanglongbing, or HLB, and it’s taking land out of citrus fast. Estimates are that Florida will produce only 50 million boxes of citrus this year. At the peak of production, Florida produced 240 million, and an average year was 150 million boxes.

“We’re down to about a quarter or a third of the citrus production we had when this scourge arrived,” Grosser says. “A lot of people are going out of business. The whole industry is collapsing.”

Why do citrus research anymore?

“Because I think we can solve this problem,” Grosser says.

Grosser and his research team want to try 10 scion/rootstock combinations on five elite new UF citrus varieties and plant them on 10 acres at the DeLuca Preserve. Recent work has revealed that micronutrients boost resistance to greening, so combining scions with new rootstock genetics and new knowledge about nutrients could make a difference, Grosser says.

The scions selected for the project are two sweet orange varieties, two red grapefruit varieties (including one that doesn’t interact with prescription drugs) and an easy-to-peel seedless tangerine, aimed at edging into the market for Halos and Cuties, which don’t grow in Florida. The rootstocks selected are “gauntlet” rootstocks, tolerant or resistant to HLB.

“There’s a jigsaw to making rootstocks work against this disease,” Grosser says. “We’re going to stack the deck for gene combinations we think work best.”

The existing trees at DeLuca look puny, and the grove is infected with HLB, but that doesn’t worry Grosser.

“You can’t hide from greening, no matter where you go in Florida. That’s the reality. We can count on there being a strong HLB presence at DeLuca, but I think the project we’re designing can handle it,” Grosser says.

“This is an opportunity to put everything together in one basket: the new rootstocks, the scions and the new science on nutrition.”

Connected Habitats

Before development plans collapsed, the DeLuca Preserve was slated for an urban future. On land use maps, it appeared as Destiny, a town of up to 250,000 people.

Maps now will show it as part of the Florida Wildlife Corridor, and people will be outnumbered by crested caracaras and grasshopper sparrows, free-roaming cows and wild turkeys. In place of golf courses, there will be hooded pitcher plants and sundews and more pines and palmettos than perhaps even the most sophisticated equipment can count.

Ducks Unlimited, the world’s largest private nonprofit group devoted to wetlands, holds a conservation easement for DeLuca Preserve and will collaborate with UF on protecting it. Tom Hoctor, the architect of the Florida Ecological Greenways Network, a science-based map that identified the corridor, says the DeLuca tract is a keystone in the region.

“The DeLuca property is an essential piece of the Florida Wildlife Corridor,” says Hoctor, director of the Center for Landscape Conservation Planning in the UF College of Design, Construction and Planning. “It’s a strategic location.”

Hoctor’s work since 1995 on the greenways network identified “critical linkages” that would chart a continuous network of protected land, making the corridor possible. In his work on habitat connectivity, he has learned how animals move across landscapes and anticipates the DeLuca Preserve will be traveled and well-used.

“Grasshopper sparrows are an indicator of healthy dry prairie,” Hoctor says. “If they’re doing well on DeLuca, that means a lot of other species that depend on a large functioning, connected landscape are going to be doing well, too.”

The dry prairie landscape itself is rare and threatened. Historically it has been dominated by both open uplands and open wetlands, but much has been converted to other uses over the past century.

Beyond the landscape and the wildlife, Hoctor says, the property is a critical linkage between two watersheds: the Kissimmee River watershed to the south and the Upper St. Johns River watershed to the north. The preserve is also part of a swath of land that contains the headwaters of the Everglades, the United States’ most endangered ecosystem.

“Having the DeLuca Preserve turned into both a conservation property in the middle of an extremely important conservation landscape and being open for this kind of research is a really unique opportunity,” Hoctor says.

With approximately 8 million acres remaining to be protected for the wildlife corridor, the DeLuca Preserve gift provides hope.

“Some people say Florida’s way too developed to protect these lands,” Hoctor says. “Well, actually, no, it’s not. Here’s the science, and here’s the map.”

Source:

Brent Sellers

Professor and Director, Range Cattle Research and Education Center, Ona

Related website:

Florida Ecological Greenways Network

http://conservation.dcp.ufl.edu/fegnproject/

Reimagining the Ocklawaha River

What if the Rodman Dam — created in the 1960s as part of the ill-fated Cross-Florida Barge Canal — was breached and the Ocklawaha River was allowed to return to its natural course?

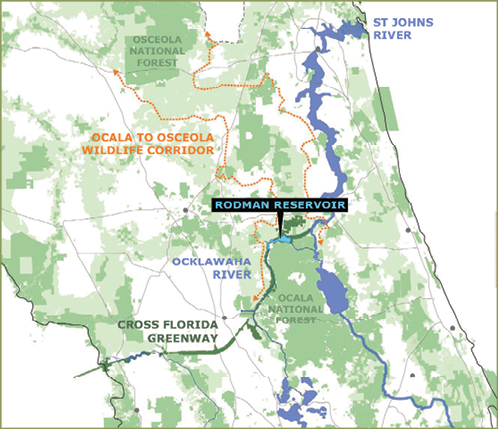

This was the challenge UF landscape architecture Associate Professor Tom Hoctor posed to his senior design class in 2020 after being approached by Free the Ocklawaha River Coalition, an advocacy group promoting breaching a portion of the dam and reconnecting the Ocklawaha and St. Johns rivers. The group maintains that a free-flowing Ocklawaha — which represents another segment of the Florida Wildlife Corridor — would have environmental benefits and would bring significant outdoor tourism dollars to the local economy in Putnam and Marion counties.

In response, 14 undergraduates developed nine recreation and restoration designs which have been featured in focus groups, community events, a viewbook for leaders, a newspaper supplement and more. This fall, senior Kathryn Stenberg took one critical project, the current Rodman Recreation Area, to the next level. In addition to a map series visually explaining partial restoration, she developed three detailed concepts for repurposing the recreation area, post restoration. These concepts helped solicit citizen feedback for her final project design.

“The student designs, particularly Kathryn’s designs, have helped us show leaders and residents of all backgrounds what they could gain in the river restoration process, not just what they will lose,” says Margaret Spontak, chair of the coalition. “The work has been the door opener to healthy conversations, opening people to change, and moving this

project forward in ways that have not occurred in 50 years.”

Hear the Story

The audio version of this story is available on our YouTube.