History professors J. Matthew Gallman of the University of Florida and Gary W. Gallagher of the University of Virginia have engaged in countless conversations with their colleagues over the years about the importance of photography to the study of the Civil War.

“People who study the Civil War era spend an enormous amount of energy thinking about and talking about photographs,” the two write in the introduction to their new book, Lens of War. “Yet, we seldom take the photograph as our subject and we almost never share personal reflections beyond our normal academic writing.”

So several years ago they asked several dozen colleagues to select one photograph taken during the Civil War that held special meaning for them and write about it.

“We wondered what would happen when scholars of the Civil War era were invited to reflect about photographs and photography in unfamiliar ways,” they write.

The result is a collection of 27 photos and accompanying essays by scholars whose numerous volumes on the Civil War have explored military, cultural, political, African American, women’s and environmental history. The essays are organized into five areas: Leaders, Soldiers, Civilians, Victims and Places.

“Taken together, the photographs suggest something of the range of subjects that the war’s photographers selected, and the roster of authors reflects the wide range of scholars who share our passion for the Civil War, and for Civil War photography,” the authors write.

J. Matthew Gallman is a professor of history at the University of Florida and author of Mastering Wartime: A Social History of Philadelphia during the Civil War, America’s Joan of Arc: The Life of Anna Elizabeth Dickinson, and Defining Duty in the Civil War: Personal Choice, Popular Culture, and the Union Home Front.

Gary W. Gallagher is the John L. Nau III Professor in the History of the American Civil War at the University of Virginia and author of nine books, including Becoming Confederates: Paths to a New National Loyalty, The Union War, and Causes Won, Lost, and Forgotten: How Hollywood and Popular Art Shape What We Know about the Civil War.

To learn more and order the book, visit https://www.ugapress.org/index.php/books/lens_war/.

Leaders

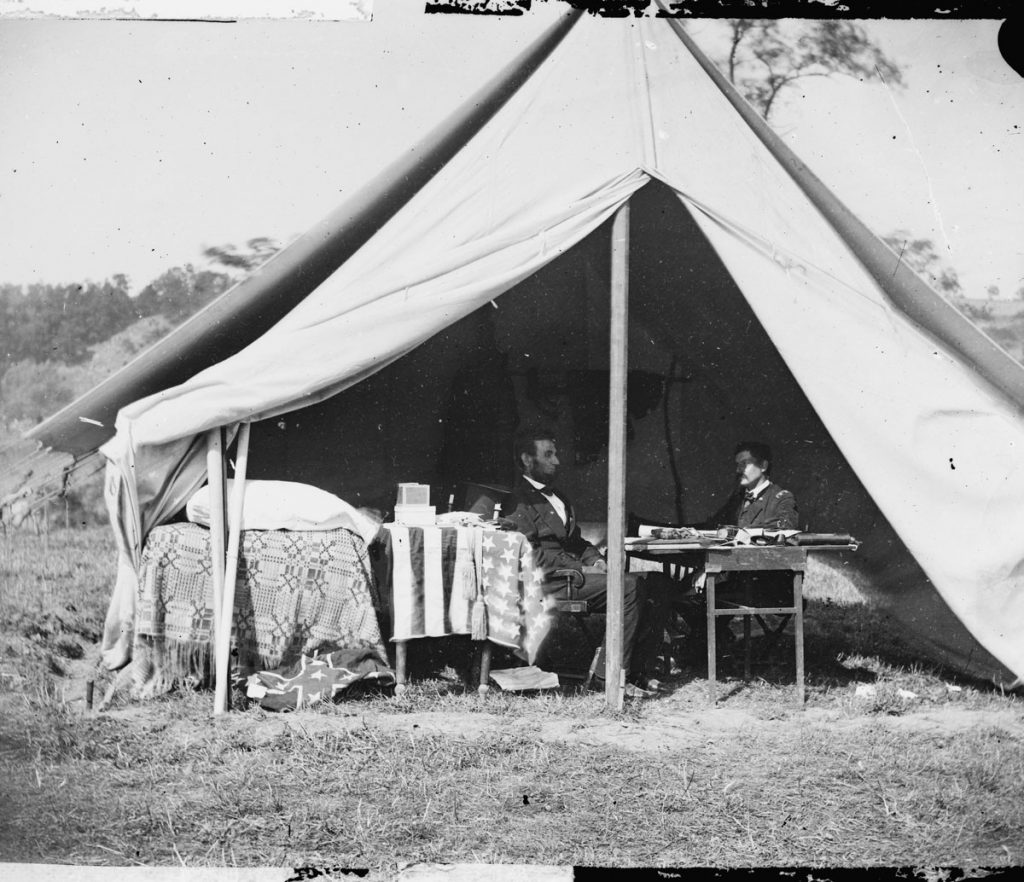

Three Roads to Antietam: George McClellan, Abraham Lincoln, and Alexander Gardner

Alexander Gardner

October, 1862

“Although we do not know precisely what the two were thinking as Gardner produced this wonderful plate, we do have a sense of the broader discussions during the short visit. Lincoln was dissatisfied with McClellan and urged that the Army of the Potomac take the conflict to the Army of Northern Virginia at the first opportunity. McClellan had little respect for his superior’s grasp of the difficulties of warfare and was frustrated that he had not garnered the abject praise that he felt his victory deserved. Gardner clearly understood that the moment was momentous.”

J. Matthew Gallman

Professor of History, University of Florida.

Soldiers

Three Confederates at Gettysburg

Mathew Brady

July 1863

“There they stand, perhaps the three most recognizable Confederate soldiers of the American Civil War. Who are they? No one really knows … Where are they? They are west of the town of Gettysburg, standing along Seminary Ridge … Most probably, the image was captured on July 15, 1863 by Mathew Brady or an assistant … Whether they were stragglers or deserters, these three Confederates standing on Seminary Ridge were also prisoners of war … I still don’t know very much about those three Confederates … I don’t know why they lost touch with the comrades or why they found themselves on the wrong side of the Potomac River … Nor do I know what fate awaited them. In each case, it’s a matter of what might have been … which, when you think about it, is what so much of Gettysburg is about.”

Brooks D. Simpson

ASU Foundation Professor of History, Arizona State University

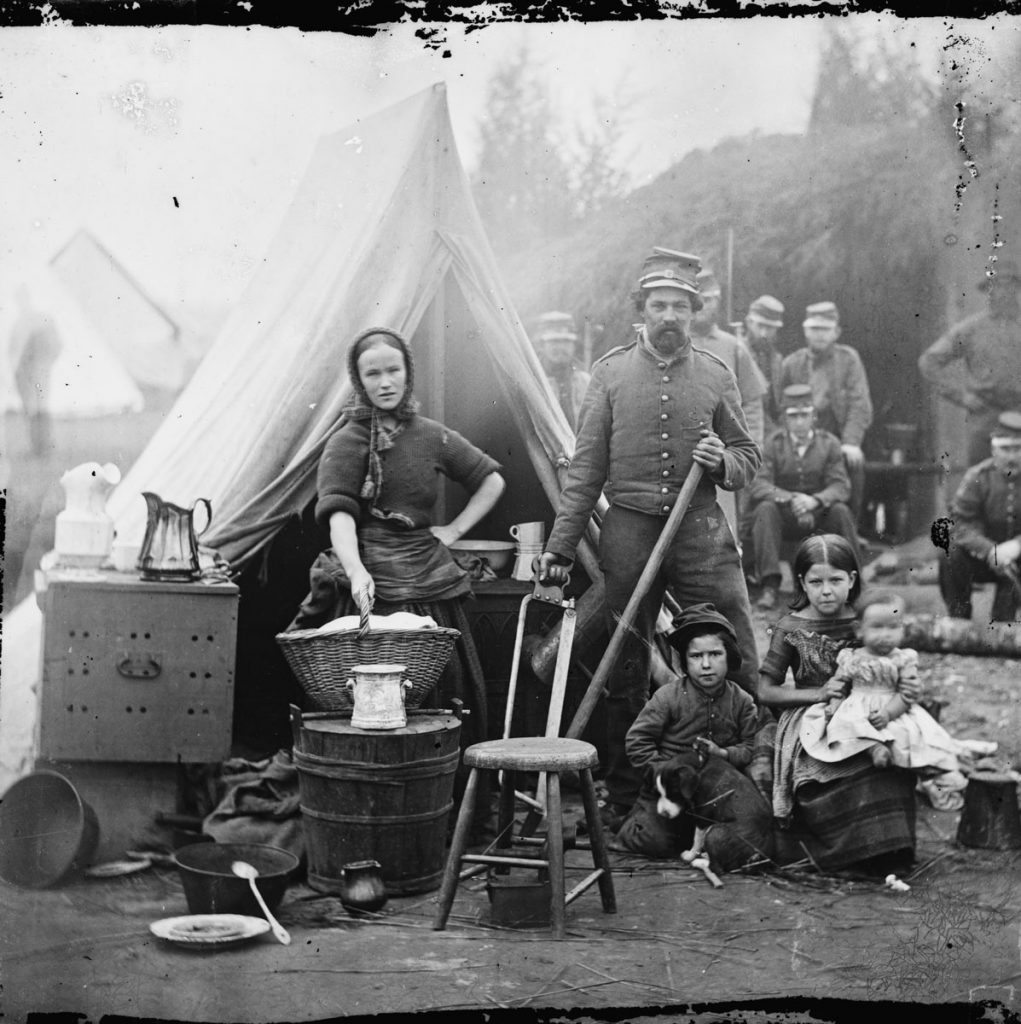

Civilians

A Family in Camp

Mathew Brady

Late 1861

“Much of the appeal of this image lies in the fact that it captures so many different aspects of the war: photography early in the conflict, the material culture of camp life, and the role of women … I am drawn to this photograph time and time again because it offers an endless source of contemplation and emotional appeal. I cannot help but be fascinated by the myriad details, from the ceramic pitchers that seem out of place in a military encampment to the hole in the woman’s sweater that suggests her humble origins. But it also leaves me with more questions than it answers: … What became of this family? Did the soldier survive? We will never know. Even so, their image serves as a poignant reminder of how far-reaching the war was even from the outset, how intimately it affected families — even Union families ostensibly far from the front lines — and how families in turn affected the Civil War.”

Caroline E. Janney

Professor of History, Purdue University

Finding a New War in an Old Image

Timothy H. O’Sullivan

Mid-August 1862

“In mid-August 1862, shortly before the Second Battle of Bull Run, one of the photographers on Mathew Brady’s staff captured what has become one of the most ubiquitous and heavily used images of the Civil War era: a photograph of five African Americans crossing the Rappahannock River near present-day Remington, Virginia … The picture O’Sullivan took … invites viewers to reconsider our more popular understandings about the war, its combatants, and especially the process by which a war for Union came to be a war against slavery … Timothy O’Sullivan probably had no idea what he captured with his camera that summer day … but with the perspective and insights of time and a rich historical record, a 21st-century audience can see beyond the surface of O’Sullivan’s enduring image to catch an important glimpse of a different war, one fought by those who have too often been dismissed as historical bystanders. The details, of course, have always been present in the image, just as slaves were always a part of a war that dramatically remade a nation. The challenge is to see what’s on the page and to read, as anthropologist Ann Stoler has advised, with (not against) the archival grain.”

Susan Eva O’Donovan

Associate Professor of History, University of Memphis

Victims

Andrew J. Russell and the Stone Wall at Fredericksburg

Andrew J. Russell

May, 1863

“Less than 24 hours after the fighting stopped, a photographer set up his equipment and exposed one of the most haunting photographs to emerge from the Civil War … this one was exposed literally within a handful of hours after the killing stopped. Moreover, the ground would be given up before the end of the day … This photograph can tell us a great deal about combat in the Civil War, but it warrants examination for what it hides as well as for what it shows. Aspects of terrain, the care of the wounded, and the experience of combat all are open to us if we take a technical approach to the photograph … This is a picture that lies at the end of the chain of links that begins with competing interests, reflected in the divisive, intransigent politics, and continue through propaganda, jingoism, saber rattling, brinksmanship, mobilization, deployment, maneuver, and engagement … In the case of ‘A Harvest of Death,’ in its relation to the billions of words written by participants in and narrators of the Civil War, I know one picture can haunt them all.”

Earl J. Hess

Steward W. McClelland Chair in History, Lincoln Memorial University

Places

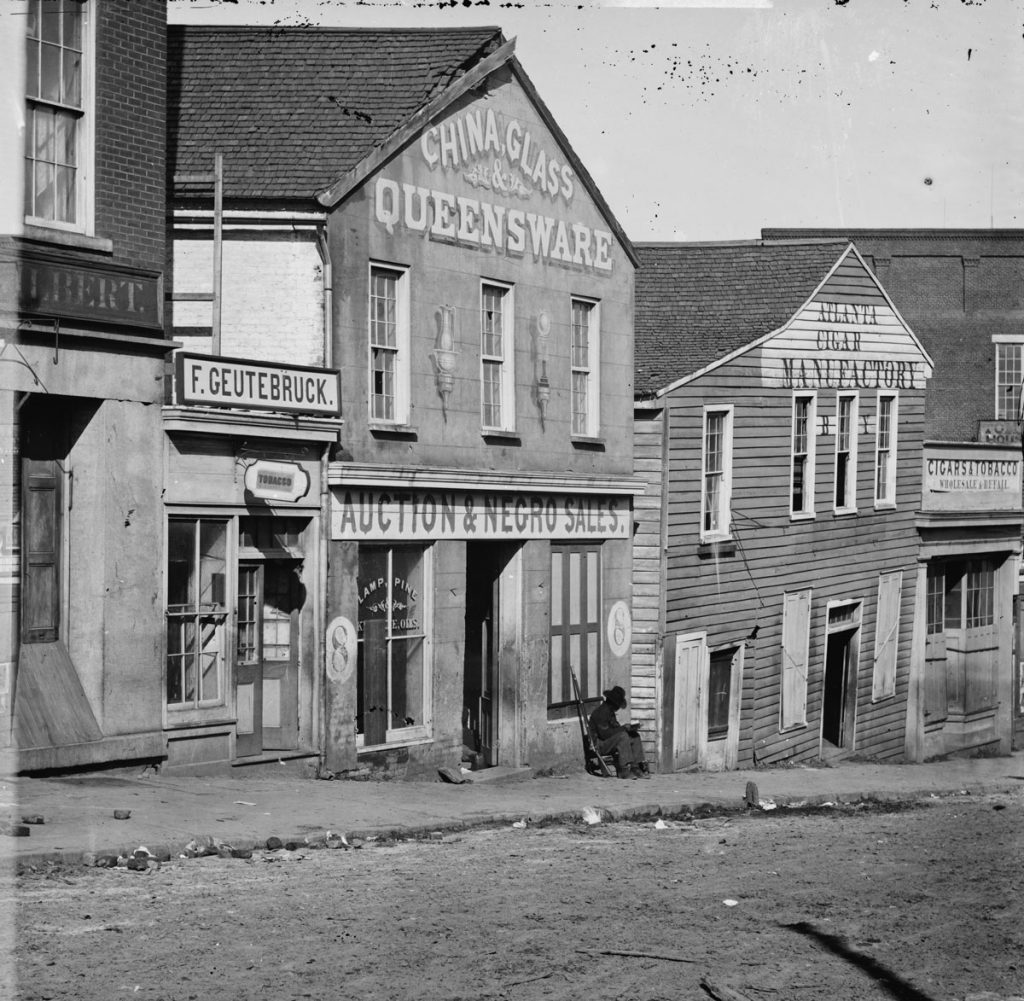

The Book or the Gun?

George N. Barnard

September, 1864

“In early September 1864, General William Tecumseh Sherman ordered Union Army photographer George N. Bernard to report to Atlanta … Before putting the city to the torch, Sherman wanted Atlanta to be photographed … At the center of Barnard’s frame is an ‘auction house,’ plastered with the banner ‘Auction & Negro Sales’ … The most arresting thing about the image, however, is the lone figure at the center. Though reprinted often, it wasn’t until the photograph was digitized and blown up that it became widely recognized that the soldier is African American. His rifle is leaning against the building, and two rocks have been drawn up to serve as his chair as he reads from a book … For here is the whole of the war in a single tableau — a war fought so that men capable of thinking and reading and dreaming might never be sold as things.”

Stephen Berry

Gregory Professor of the Civil War Era, University of Georgia

This article was originally featured in the Spring 2016 issue of Explore Magazine.