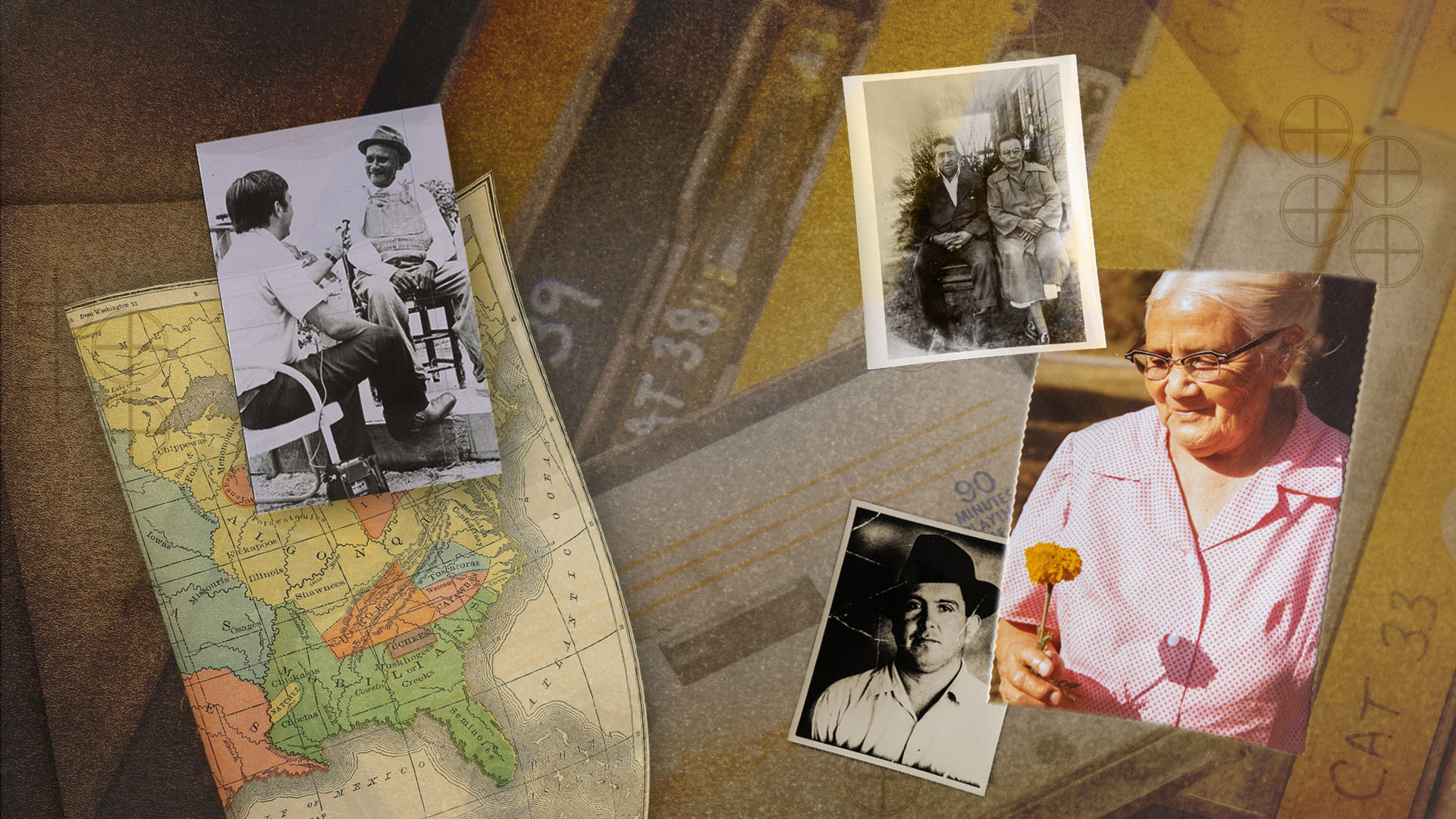

When University of Florida historian Samuel Proctor and his team of volunteers fanned out across the southeastern United States in the late 1960s to record oral histories of Native Americans, they were equipped only with their questions and portable tape recorders.

Proctor was already a leading Florida historian and oral history pioneer when tobacco heiress and philanthropist Doris Duke tapped UF and six other universities around the country to help preserve the cultures and histories of Native Americans. With a $170,000 grant from Duke, representatives of the UF Oral History Program interviewed about 1,000 Native Americans from the Seminole, Cherokee, Choctaw, Catawba, Creek and Lumbee tribes between 1966 and 1975.

“Her argument was that the library was filled with books about Indians, all written by non-Indians,” Proctor recalled in his own oral history several years before he died in 2005. “She believed that the tape recorder would give these otherwise voiceless people an opportunity to talk.”

And talk they did. Proctor and the other interviewers — including members of the tribes and faculty and graduate students from UF and other institutions around the Southeast — recorded some 800 hours of oral history.

“We really reclaimed or recovered a lot of history that otherwise would have been lost,” Proctor said.

The tapes came back to UF for transcription, on manual typewriters followed by some heavy editing with pencil, then were filed away. Although they were publicly accessible, in reality only committed scholars willing and able to come to Gainesville could access them. The same was true at the other institutions in Oklahoma, Arizona, Utah, South Dakota, New Mexico and Illinois where another 5,600 recordings were collected and archived.

In 2019, a casual conversation between the former president of the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and the former director of the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian “provided a much more substantial understanding of the breadth and rareness of the oral history collections that Doris Duke funded during her life,” according to Rumeli Banik, a senior program officer at the foundation.

The foundation hired Laura Marshall Clark, a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma, to evaluate the collections at all seven universities. Clark says the state of the collections differed widely at each institution, but that UF had some of the most complete transcripts.

Based on Clark’s analysis of the project nationwide, the foundation awarded $300,000 to the Association of Tribal Archives, Libraries, and Museums (ATALM) to “work with the seven universities and Native communities to improve culturally appropriate access to the collections; provide the originating communities with copies of all materials collected; ensure proper care of the original materials; and promote and encourage use of the collections.”

In early 2021 the foundation also awarded $1.35 million in grants to the original seven institutions — including $200,000 to UF — to “digitize, translate and index recordings and materials spanning 150 Indigenous cultures; improve their accessibility and utility to Native communities, tribal colleges, and the wider public; expand the collections to include contemporary voices; and develop related curriculums and educational resources for students and visitors.”

“The oral history project was under development before the pandemic; however, the pandemic has reinforced the importance of this effort. We recognize that the pandemic has had disproportionate impacts on the health, social and economic well-being of Indigenous communities and that Covid-19 has resulted in a high death rate in Indigenous communities and loss of the elder population, who are important culture bearers,” Banik says. “This project aligns with the foundation’s broader efforts to raise the visibility of Native experiences and increase authentic representation of Native communities and their experiences through their own stories and voices.”

Ginessa Mahar, principal investigator on the grant and anthropology librarian for UF’s George A. Smathers Libraries, says “this grant funding provides an opportunity for us as a repository to reconnect with the communities from which these materials were gathered. We’re very excited for this project, as it ensures not only the preservation of this rich cultural heritage, but does so in a meaningful way that includes repatriation and culturally responsible accessibility.”

Preserving the Past

Mahar has three degrees in anthropology, including a doctorate from UF, and she worked as an archivist and lab supervisor at the American Museum of Natural History in New York before coming to UF, but nothing she has done prepared her for the challenge of managing the Doris Duke Native American Oral History Collection at UF.

“Most of my archival experience has been with bringing materials into the digital era, especially visuals like photos and maps,” Mahar says. “But this is the first time I’ve ever worked with audio, and this is certainly the first time I’ve partnered with an oral history program.”

What Mahar and colleague Deborah Hendrix from the Samuel Proctor Oral History Project (SPOHP) found as they dove back into UF’s Native American collection was a project framed by the technologies and methods of the 1960s and ‘70s. A thorough inventory of the project materials found that the tapes were generally in good condition, but fragile. The accompanying documentation consisted of Proctor’s field notebook of interview details, index cards with basic information typed or hand-written on them, some permission slips and many examples of correspondence. The original typed transcripts and some of the index cards had been scanned in the early 2000s, but they were not searchable

“The inventory alone was enlightening, and that was the basis for the creation of our catalog and database,” Mahar says. “We ended up with over 35 linear feet of archival material.”

While the team initially considered trying to digitize the tapes in house, Mahar says it soon became clear they needed specialized expertise, so they made the “nerve-wracking” decision to pack up the tapes like they were favorite family photos and ship them off to be digitized by Preserve South, an Atlanta company that has “one of the most advanced, high-resolution, multi-track audio archiving studios in the world,” according to its website.

Before digitizing the tapes, Preserve South inspected and repaired any damage, including what is known as “sticky shed syndrome,” which Library of Congress archivists describe as a degradation of the binders that hold the magnetic particles to the tape, causing them to peel off as the tape runs through the playback equipment.

The solution is to “bake” the tapes at about 130 degrees to re-cure the binding material. After baking, Preserve South queued the tapes up and started digitizing. In the rare cases where the sound was lost, the company was usually able to use a duplicate tape to fill in gaps.

While the high resolution files Preserve South returned to UF in the summer of 2021 were a vast improvement over the old analog tapes, Hendrix is working with several students to perform additional “audio optimization” on them using three different types of software to merge tracks, eliminate background noise and enhance voices.

“We’re really just trying to make a clearer audio recording, so it’s easier for the transcription assistant to go through and get a more accurate rendition of the interview,” Mahar says. “It’s great that we can provide this kind of training for our students to enhance their future career opportunities.”

Although most of the interviews had been transcribed shortly after they were conducted, Mahar and Hendrix decided they needed to be transcribed anew. During that process Mahar says they are finding additional information, like secondary speakers on the tape or sections in Indigenous languages that were not transcribed.

To speed up the process, Mahar said they used optical character recognition, or OCR, on the scans of the original transcripts to make them editable, “and that allowed us to get a lot of the typing out of the way.” The researchers are now listening to each interview again, using these rough transcripts as a starting point, but applying modern transcription protocols that recognize not just the words that are said, but more intent, like inflection and other non-verbal elements.

Digital Repatriation

Another major goal of the project is to reconnect the oral histories with the people and tribes from which they came.

“Community engagement is a core part of this,” Mahar says. “Not only are we trying to render more accurate representations of these interviews through transcripts, we’re also working with the communities to ‘digitally repatriate’ the materials.”

“The ultimate goal really of working with these communities is not only to give them back digital copies of these interviews, but also to provide them with more autonomy over how those materials are accessed.”

The Association of Tribal Archives, Libraries, and Museums and the universities are employing a content management system called Mukurtu that describes itself as a “free, mobile and open source platform built with Indigenous communities to manage and share digital cultural heritage.”

Mukurtu allows tribes to “label third-party owned or public domain materials with added information about access, use, circulation and attribution,” according to its website.

“Cultural protocols are the core of the Mukurtu content management system,” the website continues. “Protocols make it possible to define a range of access levels for digital heritage objects and collections from completely open to strictly controlled.”

“Perhaps an indigenous group doesn’t want non-members of their communities to hear these oral histories, maybe there’s knowledge within these oral histories that outsiders should just not be privy to.” Mahar says. “Or, there could be segments within their societies that don’t have those privileges. Maybe this is knowledge that only elders should be privy to, or maybe it’s women’s knowledge that’s not appropriate for men. Mukurtu allows them to have multiple levels of accessibility either within or outside of their community.”

“There are a lot of protocols in place for tribes,” Clark adds. “Some of the more obvious topics would be ceremonies and spiritual practices or songs and chants that they might not want publicly available.”

UF museum studies master’s student Evangeline Giaconia was already looking at how museums have historically misrepresented Indigenous peoples when her experience working with Mukurtu on the Native American Oral Histories project over the last year prompted her to shift her entire research focus.

“I was a little familiar with Mukurtu from my research on museums and I thought it was a really awesome system,” Giaconia says, “so when Ginessa gave me an opportunity to learn more about Mukurtu and actually upload digital heritage items to it I jumped at the opportunity.”

The more Giaconia worked with Mukurtu, the more she realized she wanted to learn about it, until it became the subject of her master’s research. Now, she is going to study how platforms like Mukurtu bridge the gap between providing open access to historical collections and ensuring that Indigenous communities can maintain control over their heritage.

“There’s a big move to make things open access across the board these days, but when you’re working with native cultural heritage, open access is not always the preferred option,” she says. “Mukurtu is a really interesting platform that is, I think, a good mediator for those situations because of how it’s structured to allow tribal control of access on every level.”

SPOHP continued to gather Native American oral histories after the Duke project ended, including one that revisited Seminole Tribe of Florida members 30 years after the original interviews. That work resulted in a book co-authored by former SPOHP Director Julian Pleasants titled Seminole Voices: Reflections on Their Changing Society, 1970-2000 that aimed to “shed light on how the Seminoles’ society, culture, religion, government, health care, and economy had changed during a tumultuous period in Florida’s history,” according to the book’s description.

“In 1970 the Seminoles lived in relative poverty, dependent on the Bureau of Indian Affairs, tourist trade, cattle breeding, handicrafts, and truck farming. By 2006 they were operating six casinos, and in 2007 they purchased Hard Rock International for $965 million. Within one generation, the tribe moved from poverty and relative obscurity to entrepreneurial success and wealth,” according to the book description.

SPOHP is currently working with the Poarch Band of Creek Indians in Alabama. Since 2017, the program has conducted nearly 100 interviews with members of the tribe.

Beginning as part of the UF Doris Duke project in 1971, Florida State University anthropology Professor Anthony Paredes spent 13 years researching and interviewing Poarch Creek Indians. Parades provided much of the documentation the tribe used to gain federal recognition.

“Dr. Parades came into our community in the 1970s and became a well-loved person in our community,” says Dr. Deidre Dees, the tribal archivist for the Poarch Creek Indians. “We actually have the tape recorder he used to conduct his interviews in our collection.”

Dees first learned of the recordings when she was hired in 2009, and the tribe quickly moved to get them digitized.

“We began disseminating information to the tribal community as soon as we got our hands on the recordings and the transcriptions,” she says.

In 2013, her team established an “Evening with the Elders” program that regularly draws hundreds of tribal members. They play clips from the recordings and share the transcripts so people at the events can follow along. They also gather photos of the interviewees’ families to put the recordings in perspective and to bolster the tribal archives.

“We have had grandchildren, adult grandchildren, come up to us after an event with tears in their eyes because it was the first time they had heard the voice of their grandmother or grandfather,” she says.

Sources:

Ginessa Mahar

Anthropology Librarian, George A. Smathers Libraries

Deborah Hendrix

Program Coordinator, Samuel Proctor Oral History Program

Related websites:

UF Digital Collections: Samuel Proctor Oral History Program

UF Liberal Arts and Sciences: Native American History Project

Hear the Story

The audio version of this story is available on our YouTube.