Stephanie Cruz did a double take when she entered one of her computer science classes at the University of Florida in the first week of fall 2015. A woman was teaching it. A woman also was teaching the next class — and the next.

Cruz, now a senior, went from a college career in the Department of Computer and Information Science and Engineering with no women professors to three in the first week of classes.

“It was nice to finally have female professors,” Cruz says.

Jeremy Magruder, a civil engineering student in the last year of her doctoral program, is ending her studies, and has never had a woman professor in her field, although she has had women professors in electives.

Such is the experience for women in STEM — Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics — at UF and across the nation: a mixed bag.

But UF President Kent Fuchs, just two weeks into his new position in January 2015, signaled that change is coming.

He praised engineering Dean Cammy Abernathy and a leadership team that then included two women assistant deans, but said UF can do more to foster a supportive climate for women in STEM.

“We won’t have more female engineering leaders without more female engineers,” said Fuchs, an electrical engineer himself, at the Gator Engineering Leadership Summit.

An assortment of projects campuswide are aimed at increasing women student and faculty participation in STEM, among them two large grants for a combined $6.2 million that are pending before the National Science Foundation, in hopes that science can yield solutions.

The quest has prompted some unusual collaborations, including one that may be the first of its kind — certainly on campus and perhaps nationally — between the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, or MAE, and the Center for Women’s Studies and Gender Research.

Chair David Hahn was mulling over statistics on undergraduate enrollment in MAE, the largest department on campus at 1,700 students, and didn’t like what he saw. Women account for 16 percent of the students in MAE, above the 12 percent average nationally in the major but below the 20 percent overall enrollment for women in the Herbert Wertheim College of Engineering.

“Why is MAE underrepresented compared to women in engineering in general?” Hahn asks, adding, “An even bigger question is, why is engineering in general underrepresented with women when they are half of the university’s students?”

Hahn remembered meeting Bonnie Moradi, director of the Center for Women’s Studies and Gender Research, at a class for campus leaders and particularly remembered her answer to a roundtable question about what she valued in a leader. “Bonnie’s comment was ‘I like a leader that can stand up for the people who aren’t necessarily included.’”

The comment resonated. What if women in engineering did not feel included? Hahn and Moradi brainstormed, and today they are seeking a $1.3 million NSF grant, based on research they started with a Seed Opportunity Fund grant from the Office of Research.

Moradi welcomed the chance to develop a model that could solve UF’s problem and perhaps be useful in the global issue of women’s low participation in some STEM fields. She suggested integrating feminist scholarship on subtle gender bias with social cognitive career theory, which aims to explain how students develop career interests and make choices about careers and how they achieve success.

Moradi and Hahn say applying feminist analysis and science to the issue is key. People have strong convictions about their ideas on gender, reinforced by personal experiences. But conventional wisdom has failed to explain why women do not enroll in some STEM fields in the same numbers as men, especially as institutional barriers have fallen.

“Conventional wisdom often is not supported by data, so our job is to apply a higher level of scrutiny to those ideas,” Moradi says. “Rather than relying on stereotypes — this is how women are, this is how men are — we will apply scientific theory and research informed by feminist analysis.”

A Leaky Pipeline

If STEM fields are viewed as a pipeline, more women than men leak from the pipeline as they travel through the academy. Overall, women graduate from college at a higher rate than men, according to NSF’s 2014 biannual report, Science and Engineering Indicators. Women earned 993,872 bachelor’s degrees in 2011, the latest year in the report, compared to 740,357 for men.

A disparity shows up in engineering and some other sciences, however:

- In all engineering fields, women earned 14,658 bachelor’s degrees, men earned 63,441.

- Overall, women earned significantly more master’s degrees — 443,154 to 293,301. However, women earned 9,339 master’s degrees in engineering, men earned 31,943.

- Overall, women earned 29,513 doctoral degrees, men earned 30,334. In engineering, women earned 1,898 doctorates, men earned 6,580.

- In the STEM workforce, women cluster into different fields than men, with women representing 58 percent of the social science work force and 48 percent of the life science work force, but 13 percent of the engineering work force and 25 percent of the computer science and math work force.

- In the academy, women make up less than 25 percent of full-time full professors who hold science, engineering and health doctorates, according to NSF figures for 2013.

Hahn said the attrition of women in engineering has dire consequences because their design perspective is lost, and Moradi points out that early airbags actually were dangerous to smaller women and children because the design was based on an average-size man.

“We get them in the door, but they go right out the door, and that’s a real shame. We can’t afford to exclude half our population from helping us solve our big problems: food, water, security, health care, energy. Without them, we’re doomed,” Hahn says. “Getting women to our doorstep, and then losing them, is even worse than not getting them to the doorstep. They were right there, we almost had them. What’s happening?”

Opening Doors

Attrition in engineering is a problem for all students, men included, and that’s one focus of a White House initiative aimed at keeping students in STEM. UF was one of 10 universities asked last year to participate in the initiative. But attrition is much higher for women STEM students.

Hahn says engineering saw an influx of women students as institutional barriers began to fall in the 1970s. Still, they were not necessarily welcome, say Angela Lindner and Linda Parker Hudson, who studied engineering in that era.

Hudson, known as the first lady of defense because she was the first woman CEO of a defense company, was one of two women to earn an engineering degree at UF in 1972.

Hudson says role models like Abernathy, appointed UF’s first woman engineering dean in 2009, are invaluable.

“For me, there were no women role models,” Hudson says. “I was the first woman to ever hold almost every job I had.”

Hudson said it was important to her that she succeed: “If I failed, no other woman would have the opportunity.”

The success of Hudson and Lindner, who got a chemical engineering degree in the 1980s and an environmental engineering degree in the 1990s, set the stage for the women who came after. Lindner, a former associate dean in engineering and now an associate provost, says she has seen UF’s freshman class of women engineering majors grow each year, to about 25 percent in 2015, above the national average.

One reason the pipeline leaks in engineering is a happy reason: the lure of the job market. Unlike some fields, even other STEM fields, engineers with bachelor’s degrees get great jobs.

Women like Hudson and Lindner helped overcome institutional barriers for women engineering students, and enrollment rose in the 1970s, before it hit a plateau. Enrollment rose again in the 1990s, then plateaued again. This plateau, Hahn says, has been stubborn.

To investigate the reasons, Hahn and Moradi have used the seed funding to gather a wealth of information – 10 years of data on women students’ AP credits, internships, class combinations, grades and more. They will mine 6,000 datasets for information that might predict attrition and help them devise interventions. Are there setbacks, struggling in calculus or physics, for example, that play a larger role in attrition of women? A “B” in physics might be viewed as positive by a male student, but perhaps as an ominous sign by a female student, they say.

Anne Donnelly, director of the Center for Undergraduate Research and one of 15 recipients of the Presidential Award for Excellence in Science, Mathematics and Engineering Mentoring recognized by the White House in 2015, says women who leave engineering have equal or higher GPAs than the men who stay, so ability is not the issue.

Moradi and Hahn agree.

“Is there a combination of subtle gender bias and a perceived academic setback that changes the whole course of their career?” Hahn asks.

Seeing women who have survived and entered the academy is important, Lindner says, recalling a story, an object lesson of sorts, from one of UF’s pioneer women in engineering.

The woman professor, now retired, told Lindner that she once asked her preschool-age son what he wanted to be when he grew up and suggested being an engineer. His response?

“No, mom, girls do that.”

“His mom was an engineer, so he viewed women as engineers,” Lindner recalls. “So the message is that we need strength in numbers, and then people’s perceptions will change.”

See It, Be It

One person who has taken that message to heart is CISE chair Juan Gilbert.

Although the odds were against him — from 2000 to 2011, computer science bachelor’s degrees awarded to women nationwide declined 10 percent, according to NSF — Gilbert has transformed the CISE department, which he says has the highest number of women of color on a computer science faculty in the country.

“It is a very different environment here than anywhere else in the country, if not the world,” says Gilbert, adding that the department promoted a woman to full professor in 2015, a first. “We’re the largest producer of African-American Ph.D.s. in the country, and the majority of them are women.”

Gilbert says he learned a valuable lesson observing his Chinese classmates in graduate school. He wondered how they managed to learn a new language, adapt to a new country and excel in their studies. The answer, he says, is that they created a community.

“There was always one person at every stage, and the person in front left footprints in the sand,” Gilbert says. “They had each other all the way through.”

Isolation, Gilbert says, is the downfall of Ph.D. students who are not in the majority. He resolved when he became a professor to always recruit two minority students at a time, so no one would ever be isolated. He also gave his students a say in who was recruited into the lab, and the women students took it to heart.

“It morphed. The women in the lab said, ‘We’re very happy here, so we’ll recruit more people,’ and that’s how it all began.”

Jessica Jones, one of nine women out of 12 total doctoral students in Gilbert’s lab, can vouch for the environment. Having women at each stage is key; what does a woman computer science professor look like?

“You can’t be it, if you’ve never seen it,” says Jones, who is on a Department of Defense fellowship and has aspirations to be an astronaut.

Gilbert says some male administrators make a key mistake with good intentions. They set out to hire a woman.

“A woman. One woman. That’s the problem,” Gilbert says. “If you isolate people, you increase the chances they’ll leave.

“It’s not that these guys have something against women. If anything they have a blind spot; they never see them because it wasn’t part of their development through their own curriculum,” Gilbert says. “They just don’t see them.”

Gilbert says cluster hires, like his move from Clemson with five faculty, two postdocs and 20 Ph.D. students, change an environment almost overnight. Oftentimes, he says, people will move in a cluster who will not move for a “token” appointment.

Jones says recruiting for Gilbert’s lab is easy.

“Dr. Gilbert is an example of someone who just decided that computer science can look more than one way,” Jones says. “Brilliant computer scientists can come in all genders, all races.”

Martin Cohn’s lab is another place where women are leading the way. Cohn, a developmental biologist in the UF Genetics Institute, says he didn’t necessarily intend that 16 of the 19 people in the lab would be female, it just worked out that way.

“I know that my selection criteria are simple — I really want the best people in the lab,” Cohn says. “I just want to do science with great people. Not just great science — great people.”

Cohn recognizes that his lab mates face challenges he didn’t face, so he has invited female colleagues to lab meetings to discuss their careers, how much the women want to “lean in,” and how best to go about it.

“My experience as a man in science has just been different,” Cohn says. “I haven’t been asked the same kinds of questions that women are asked. And the questions they were asking me I couldn’t answer.”

The Balancing Act

The only advice Jones says she would not seek from Gilbert is advice on work-life balance. Having women faculty members is important to women graduate students, who are at an age when dating, marriage and family collide with classes and research, she says.

For role models, Jones has a woman professor who is a mother, another who is single and can talk about dating, another she can turn to for advice on negotiating and job searches.

“They would give me a nuanced answer I might not get from a male faculty member,” Jones says.

Jones says her only five minutes of doubt about computer science came in high school.

“I took a computer science class, and I walked in, and it was all guys. They were all talking to each other, but nobody acknowledged me. I didn’t feel like I belonged,” Jones says. “I was ready to walk out when the teacher walked in. She was a woman. I wonder what I would have majored in if she hadn’t walked in.”

Donnelly says even with mentors, women graduate students often face issues their male counterparts do not. Doctoral programs already experience high attrition, but being a woman and being a parent increases the risk. At UF, there is a support group, Ph.D. Moms, also open to dads. “Family burdens don’t go away just because you’re a female Ph.D. student,” Donnelly says. “I had two Ph.D. students, women, who were taking their mothers to chemotherapy while they were students.”

It is difficult to boost the numbers of female faculty if women take time out to have children, or raise a family, because they are not in the pipeline long enough to navigate the process of getting a faculty job, then getting tenure, Donnelly says.

“It’s one thing to have numbers, but are we keeping them, and are they happy?” Donnelly asks.

Social Media

Women in STEM have often sought support from each other, and one group at UF is WISE, Women in Science and Engineering, which sponsors camps and workshops. Social media helps the group connect with women and do outreach, notes adviser Emily Sessa, a biology assistant professor.

Like other women scientists, Sessa also has noted the profound effect of social media on exposing sexism in STEM. Twitter, she says, has become a tool for accountability.

In 2014, space science made history when the Rosetta mission landed a spacecraft on a comet. A male Rosetta scientist gave interviews wearing a shirt covered with scantily clad women and made suggestive comments (“Rosetta is sexy, but I never said she was easy.”) He apologized.

In 2015, Nobel prize winner Tim Hunt expounded on the “trouble with girls” in laboratories, saying they either fell in love with a mentor or were reduced to tears by criticism. Hunt lost his honorary professorship.

Suddenly, conversations women scientists had been having by the water cooler went not only public, but viral, shining a light, Sessa says, on longstanding issues. Sessa refers to the Rosetta incident as #shirtgate, just one of the hashtags that generated over 50 million views. “The fact that people don’t understand why a shirt covered with naked women might be offensive … it’s great that women are more than 50 percent of biology bachelor’s degrees, but it’s frustrating that this stuff still happens.

“In the past, these things would not have gone beyond the department or campus,” Sessa says. “Twitter exposed these incidents in a way they had not been exposed in the past. Few people would have believed Hunt’s comments, but he was on tape, and then on Twitter, and then in the news. Twitter is a really powerful tool for overcoming these kinds of things.”

Sessa, a specialist in the evolution of ferns, says she is one of the lucky women in science. She had mentors who were women or who were strong advocates for women in science. At UF, the biology faculty, both men and women, suggest women for openings, and the department chair is a woman.

She says she is both an optimist and a feminist. Although it’s great that women are 59 percent of biology bachelor’s degrees nationally and at or above parity in fields like medicine, attitudes need to change along with the numbers.

“Women need to be respected in ways that they’re not,” Sessa says. “Fundamentally, we need to change the way we think about and speak about women, and men.”

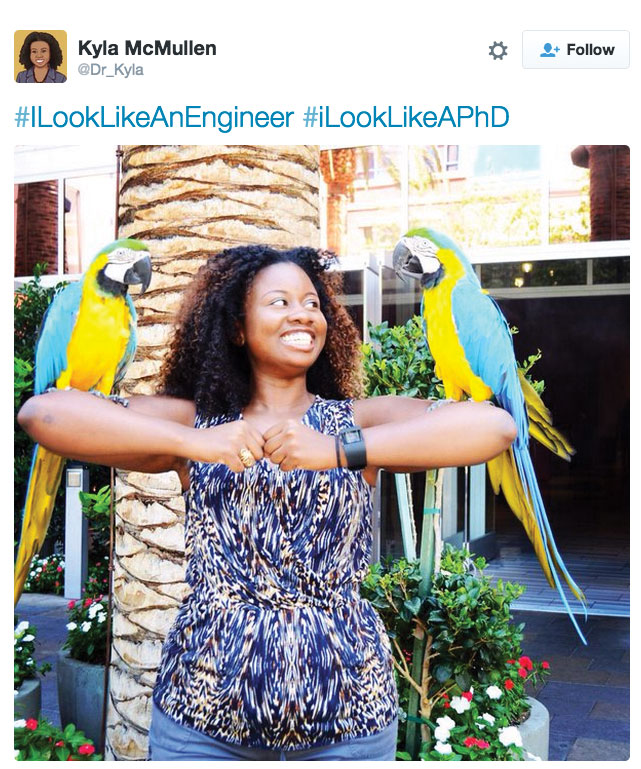

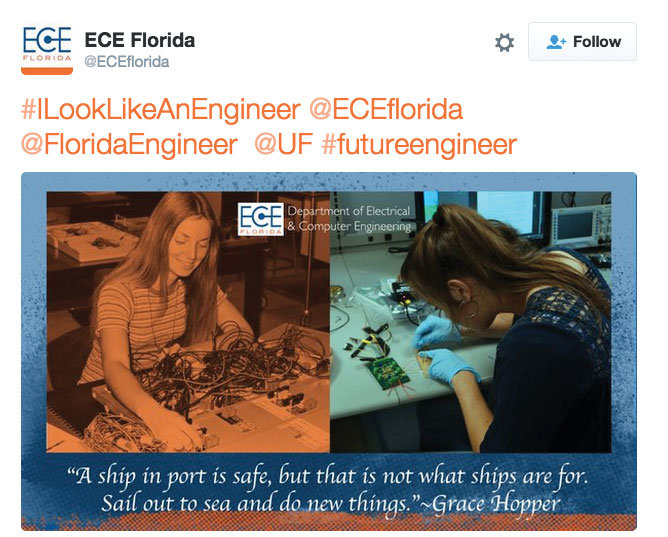

Social media can also reinforce positive messages and create community. In 2015, a hashtag took Twitter by storm, when a California engineer, told she didn’t look like an engineer should look, tweeted a photo of herself with #ilooklikeanengineer.

What is an engineer supposed to look like? At least 100,000 ways, and counting. The hashtag did not disappear into the Twitterverse. Women — and men — still post to the hashtag today. Among the tweeters was alumna Linda Parker Hudson.

Hudson says she was moved to tweet because she felt it was important that engineers not be stereotyped. “Engineers come in all shapes, sizes, ages, types, genders,” Hudson says. “Anybody can do it.”

Photos By: John Jernigan

Ellison Langford contributed to this story.

Sources:

- Juan Gilbert, Professor and Chair of Computer and Information, Science and Engineering

- David Hahn, Professor and Chair of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering

Bonnie Moradi, Professor of Psychology and Director of the Center for Women’s Studies and Gender Research

Related Website:

This article was originally featured in the Spring 2016 issue of Explore Magazine.