On the map of life, of biodiversity on the planet, there are patches that are unknown, as if a hiker spilled coffee and covered up a chunk here and there. A hiker might have trouble using such a map and so does a scientist struggling to understand Earth’s biodiversity even as it declines.

Even with more than 600 million biodiversity records virtually available on any smartphone, filling in the patches will require still more data.

For a data analytics fan like Robert Guralnick, that’s like an endless dessert bar. As the associate curator of informatics at the Florida Museum of Natural History, Guralnick’s role is to use technology to place the museum’s resources — not just the specimens but the data housed in the cloud or refrigerator-sized mainframe computers — into the hands of those who can use it and position that data within the larger ecosystem of natural history information worldwide.

“What do 600 million biodiversity records tell us about what we know about the planet?” asks Guralnick.

Mostly, those records tell us how much more there is to know.

“We know the spatial distributions of biodiversity in places that are well sampled. But some places on the map are empty; we need more data to tell the story. And it’s an important story.”

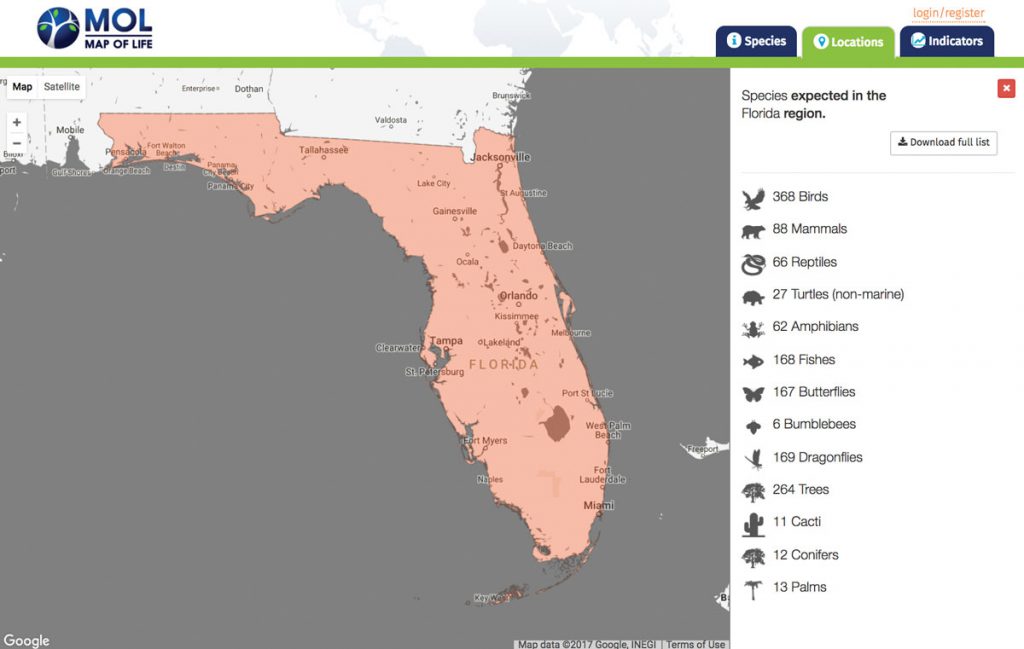

The 600 million records Guralnick refers to reside in the Map of Life app, developed by Guralnick and a colleague, Walter Jetz at Yale University. Anyone with a smartphone can access it, and use it multiple ways. First, it serves as a field guide. That tattered guide to butterflies, perhaps several volumes worth, can stay on your shelf at home. Just download the app and take your phone along and you can learn about butterflies and biodiversity wherever you happen to be. If an interesting plant or animal stops you in your tracks on a nature walk — or an urban walk — check the app.

Want to contribute? Report what you saw and when and where with the GPS on your phone to help track biodiversity around the globe. Guralnick imagines an army of globe-trotting smartphone users adding data as they go.

If your curiosity, or a research project, requires it, you can query the entire dataset, all 600 million records, in about a minute and in six languages. For conservation managers who need data for decision-making, the data can be confined to a particular area of interest, such as a national park. As a user, you can email your own records to yourself and keep track of what you have seen. It’s a robust tool, whether used casually or scientifically.

“There is a lot of simplicity to the app,” says Guralnick, “but at the heart, it’s a very difficult thing to pull off. Intellectually, it’s rigorous and challenging, but Walter and I have always known in our hearts that out of that rigorous science would be something easy for people to understand.”

So easy, in fact, that the American Association of School Librarians named it a Best App for Teaching and Learning in 2016.

“Wherever you are on the planet, you can find out something about the biodiversity there,” Guralnick says.

Web to App

The sophistication of the Map of Life is a long way from Guralnick’s web roots.

Think back, to the computers on your desk in the early 1990s. Chances are, you were transitioning from five-inch floppies to three-inch diskettes, occasionally whacking the boxy machine or jabbing a keyboard repeatedly, unaware of the paradigm shift at hand.

But not Guralnick. In 1992, Guralnick was sitting in a lab in Berkeley, a graduate student at the Museum of Paleontology at the University of California, transfixed by the clunky technology that frustrated others. In the electronic box on his desk, and the ether it connected to, he saw a way to give the public access to fossils cloistered away in the collection. He built one of the world’s first 50 web sites, one of only two or three at the time that were searchable. Did he feel like a pioneer?

“No question about it. I had a sense in real time of what we were doing. I knew,” Guralnick says. “It was one of the few times in my life where I was sure what I was doing was important.”

Not everyone shared the vision. His mentor predicted web sites would be a flash in the pan but let Guralnick geek out. A couple of years later, the mentor allowed that web sites, even museum web sites, might be around to stay. Guralnick, meanwhile, had been giving talks about the web to companies like Disney because there were so few folks with hands-on experience.

“We just had hints of what the transformations would be with the new digital technologies. But we recognized we were giving people a window into discovering content,” Guralnick says.

Before the web, a scientist or student searching for a fossil would follow a laborious process, talking to a collection manager, perhaps several at different museums, then arranging a loan of the specimen. Those with grant funding might have the means to travel to view specimens, only to find a particular object was not quite the right specimen. Overnight, Guralnick says, that changed.

“The web democratized the data, made it widely available. It got our stuff out of boxes and into people’s hands.”

Museums embraced the information revolution because what any collection manager wants most of all is for others to see and value their stuff. Another benefit: In cramped museum collections, space is at a premium, but in the cloud, there’s plenty of room, making it a huge resource for the information ecosystem of natural history museums.

Once an object is in the cloud, it emerges into a world of possibility. Only a handful of people may know an object exists in a museum drawer, but a student, scientist or hobbyist might bump into it online. Then they can explore, perhaps learning genomics, or morphology or other information enriched beyond the object in the drawer.

That prospect for discovery and deepening the knowledge held in each object is what Guralnick is after. In that open access model, the museum’s data does not belong just to the museum anymore; it belongs to anyone.

Technological Toolbox

Although Guralnick has spent eight years working on the Map of Life, it is just one tool. Guralnick has a hand in several others and an eye out for any new ways on the horizon to leverage technology.

Before he arrived, the museum was already knee-deep in iDigBio, leading a 10-year collaborative effort with a $12 million grant from the National Science Foundation to digitize the massive biological collections tucked away at UF and other natural history museums nationwide. In fact, iDigBio was one of the reasons Guralnick was attracted to UF.

One area of particular interest is how to get the public involved in the process of digitization. Guralnick and a team of partners created a citizen science platform called Notes from Nature, that asks the public to help with the challenge of digitizing critical biodiversity information contained on each imaged specimen. He was part of a team that developed weDigBio, the Worldwide Engagement for Digitizing Biocollections, an annual event in which volunteers transcribe specimen records so they can be placed online. The 2016 event spanned four countries and resulted in 35,000 transcriptions.

A 2010 estimate puts natural history collections at two to four billion objects worldwide. Of these, perhaps 5 to 10 percent are available online, making digitizing a critical step in using museum data. Without knowing what’s there, it is not possible to assess human impacts or environmental changes and then use that information to figure out the changes still to come for the planet.

“The really awesome thing about the 21st century, about the next 20 years, is we will be able to go beyond the who, what, when and where of our collections,” Guralnick says. “To ask questions about global change, to understand drivers of change, we need to assemble a better mousetrap, and that means bringing together very rich, very complex, very heterogeneous types of data. We’ve monitored biodiversity for hundreds of years, but our specimens are so much richer, they can tell us so much more.”

Heartened by the community of collaborators he found at UF, Guralnick dove in to a diverse set of projects with big data needs, 10 since his arrival in 2015.

With Akito Kawahara and a $2.5 million NSF grant, Guralnick is developing ButterflyNet, an online database and toolbox for comparative studies of butterflies, with the aim of reconstructing the evolutionary history of about 18,000 butterfly species [see related story, page 34]. A smaller project, CreatureFeatures, will build a toolkit for aggregating and annotating trait data for a variety of organisms.

Guralnick admits he may be guilty of collaborating too much, but when someone comes to him with an idea to tap technology for science, it’s hard to resist. The transformative value is not just in the whiz-bang of novel technology; it’s in the knowledge technology sets loose.

As an evolutionary biologist, Guralnick says, change is the rule, not an exception, so maybe that’s why he’s right at home with the moving target of technology. People talk a lot about big data, he says, but it will take big data to answer the big questions.

“This is our century, for biodiversity and ecosystem scientists,” Guralnick says. “We will be able to pull together the systems and how they are changing, and that can help serve as alarms for the planet. We need to be able to run the clock forward from a period in the past to the present and use that to calibrate the future.

“To do that, either you get a time machine, or you go work in a natural history collection.”

Photo Credits: Kristen Grace

Source:

- Doug Jones, Florida Museum Director

Related Website:

This article was originally featured in the Spring 2017 issue of Explore Magazine.