When you walk into your voting booth, chances are you think you are choosing the politicians who will represent you.

Actually, says University of Florida political scientist Michael McDonald, the politicians already have chosen you.

The shapes of voting districts — from school board to U.S. Senate — dictate much of an election before voters ever show up to cast ballots, says McDonald, who has studied the science of these political shapes from his earliest days in political science. McDonald says the way we draw these political districts affects the very health of our democracy.

The process is seemingly so simple: draw lines to sort voters into evenly populated districts. And yet it is maddeningly complex: do the voting boundaries respect geographic borders, for example, by keeping next-door neighbors in the same district? Do the boundaries allow all populations a reasonable chance at electing a representative? Are they fair?

Letting a computer handle the job seems like a reasonable solution, drawing perfectly apportioned squares and rectangles, but that would not be fair or sensible either. Those lines could go down the middle of a house, for example.

It is this complexity that has kept redistricting in the hands of incumbent politicians in the proverbial smoke-filled rooms for so long. By controlling their districts, politicians control voters, and they rely on voters’ disinterest in the tedious process, hours on end of drawing and erasing lines. After all, who wants to dive into this murky process?

As it turns out, McDonald did, and as a self-professed elections geek, he has come up with a way to draw districts that is transparent, easy to use, computerized and … fun.

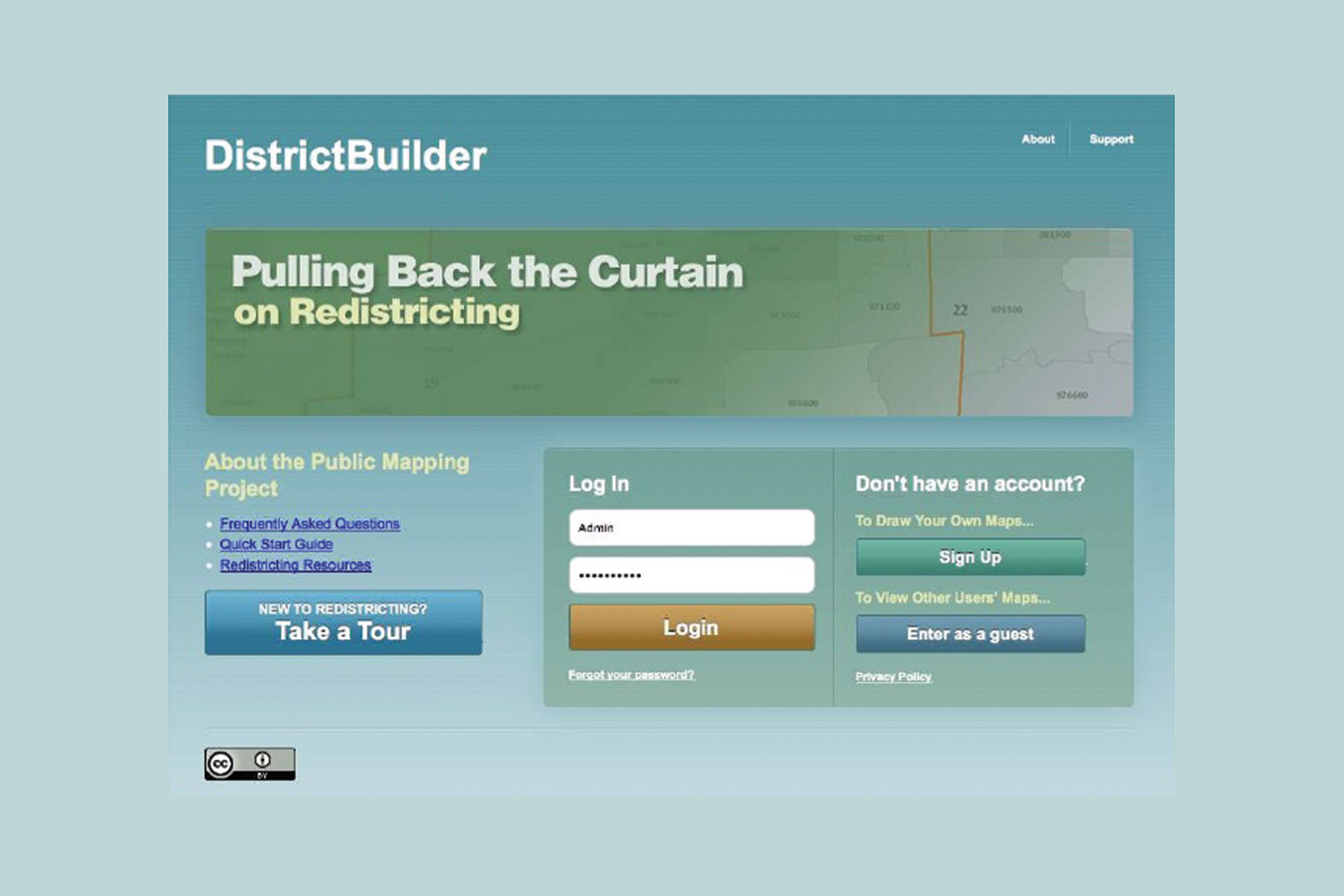

At redistricting competitions across the United States, college students, regular citizens and even a 10-year-old have tackled districtbuilder.org, developed by McDonald and Micah Altman, a colleague at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Student plans have even been used as a foundation for some districts, such as in Virginia, where a district was created that increased minority representation in Congress.

“That was something that had never happened before, students coming up with a very complex map, and it was actually legal,” McDonald says. “The student maps were more fair than the politician-created maps.”

It’s enough to make Elbridge Gerry turn over in his grave. Gerrymandering, the practice of drawing districts to favor one party or the other, gets its name from the Massachusetts governor who, in 1812, presided over a district so convoluted that an opposition newspaper compared it to a salamander, hence the gerrymander. Can software cure the gerrymander? McDonald hopes so.

“I work with Democrats, and I work with Republicans, but I don’t like gerrymandering,” McDonald says. “I don’t care who’s doing it.”

McDonald has watched the software at work across the U.S. Everywhere, citizens embraced districtbuilder.org, drawing lines according to their local rules and engaging in the political process. In Minneapolis, the first Somali and the first Latino were elected to the City Council, using publicly drawn districts that impressed the council enough to adopt them.

“We’ve gone well beyond whether it is possible for the public to draw maps to the ideal of collaborative mapping and representational gains for underrepresented communities,” McDonald says. “We can do that in every state.”

The Hybrid

McDonald moves freely between the worlds of computer science and social science, an unusual hybrid. He started out as an electrical engineering and computer science major at Caltech then switched to economics when he became interested in applying math to human behavior. Upon graduation in 1989, he worked on California reapportionment and for a campaign that was using software to microtarget voting districts.

The program was clunky.

“I was the only person on the ground who could use that software,” McDonald says.

In the next election cycle, McDonald offered to produce something better, and they told him to go for it.

“In a month, I wrote a program for microtargeting that the party adopted for 14 races,” McDonald says. “They won 13.”

The marriage of technology with political science suited him, and in his dissertation at the University of California San Diego, he tackled an age-old problem — can computers solve the challenges of redistricting — then went on to Harvard for a post-doctoral fellowship, where he met Altman. They began collaborating on redistricting software and presented an early version in 2007 at an American Mathematical

Association meeting, not a typical conference for political scientists. An officer from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation was in the audience. He liked McDonald’s approach of using software but having people at the controls and contributed $1.5 million to develop the software and data.

McDonald and Altman worked to make districtbuilder.org even easier to use, with clues for users on whether the districts they were drawing were meeting the constitutional requirements of the state they were in. They added social media functions and collaborative functions, so users could share maps or even single districts. The whole system operated through a web browser, eliminating the need for special equipment.

By 2011, Virginia was in the midst of redistricting and districtbuilder.org had reached a turning point, highly developed, well-studied but not tested by the public. To accomplish that test run, McDonald decided to “crowdsource” redistricting. There had been redistricting competitions using old data or phony data. Why not try it for real?

“It was the first time ever there was a redistricting competition using real data in real time,” McDonald says.

The competitions were a hit — one even included a 10-year-old who won second place — and McDonald got valuable feedback on the software, which is open source, allowing anyone with the right skillset to use it, adapt it to their needs, and add to it. McDonald says a government official in Vermont called him out of the blue one day to ask a technical question, and McDonald told him he and Altman had not built that feature yet. No problem, the guy said, he’d do it.

“That’s the point of open source — having a community of people developing tools and making it better for everybody. The other thing about open source is everyone can evaluate what the code is doing. If they don’t think something is fair, they can evaluate it for themselves. It’s transparent.”

Florida has had its own journey through redistricting. In December 2015, the Florida Supreme Court approved a congressional district map after four exhausting years of bickering over how to sort voters into 27 districts. There’s a chance, McDonald says, that one of his students, using districtbuilder.org, could have done it in days, or even hours.

For politicians, however, a transparent, open process that engages the public could be disastrous. McDonald says politicians have little to lose from making the process labyrinthine and engaging in gerrymandering.

“It’s sad to say, but there’s no incentive for a legislature not to gerrymander and wait for the courts to overturn their plans. The longer the process takes, the more elections can be held under redistricting maps that favor the party in power,” McDonald says. “Who pays for it? The voters, the citizens, the taxpayers who fund that litigation.

“Redistricting has a role in the corrosive politics we see today. With each redistricting cycle there are fewer and fewer competitive districts because they are not in the interest of the politicians,” McDonald says. “We’ve hollowed out the middle.

“There are lots of other things going wrong in our democracy,” McDonald says. “But this is one we can get a handle on.”

Turnout by the Numbers

Redistricting is not McDonald’s only election obsession. By challenging the conventional wisdom a decade or so ago that fewer voters were going to the polls, he also became the nation’s guru of voter turnout.

Voter engagement, as it turns out, was stable. What had changed was that the number of ineligible voters had grown. From 1972-98, the non-citizen population of the U.S. grew from 2 percent to 8.5 percent. When they were removed from the equations, voter turnout was stable over time.

A 2001 paper co-authored by McDonald and colleague Samuel Popkin, titled “The Myth of the Vanishing Voter,” is one of the most-cited articles in political science.

Debunking the myth took data, however, and McDonald says it was clear then that better data were needed, so he started the United States Elections Project, www.electproject.org. The site — which aims “to provide timely and accurate election statistics, electoral laws, research reports and other useful information regarding the United States electoral system” — contains an archive of voter turnout data, along with a wealth of other data and useful links.

McDonald’s skill crunching election numbers has made him a popular source for national media. In 2002 he helped ABC News “kluge together a system, a kind of Frankenstein system, on the fly in under a week,” after the network’s exit polling software failed a pre-election night test. With the revamped system, “ABC was calling everything faster than anyone else” on election night, McDonald says.

“I’m a very good data rat as it turns out.”

On election night 2016, McDonald expects reporters will be hounding him with voice mails and texts right up until he tweets his numbers in the wee hours of the morning.

“And that’s the number you read on the front page of the newspaper or hear on the morning newscast,” he says.

In preparation for the 2020 round of redistricting in the wake of that census, McDonald is working with a group of students and others on national voter registration, to take data from all the states and share it with the Census Bureau. Although partisan companies already pull some of this data together, McDonald says a centralized impartial database is needed for non-partisan applications, such as academic research. The kind of database he wants to build would help the Census Bureau, too, by providing more accurate population-based statistics.

Viewing the chaos of voting and elections through the prism of science and bringing order to it is one of McDonald’s goals in districtbuilder.org, the U.S. Elections Projects and a future UF Elections Science Research Center. Ultimately, he says data and democracy go hand in hand.

“Big data itself can’t tell us everything we want to know, we have to be able to interpret it. And so the social science background is very important, otherwise this is just data, and valueless.”

Source:

- Michael McDonald, Associate Professor of Political Science

Related Websites:

This article was originally featured in the Fall 2016 issue of Explore Magazine.