Shauna Quirk has a degree in Spanish and arrived at a career in teaching by roundabout means.

So a few years ago, when she found herself facing a room full of kindergartners eager to learn to read, she also came face to face with a realization.

“There was a lot I didn’t know,” Quirk says.

That year, 2017, the University of Florida’s Lastinger Center for Learning was piloting a new literacy program called the Flamingo Literacy Matrix. Figuring she had a lot to gain, Quirk signed up. And her toolbox grew.

“Almost right away, I found I could apply the lessons I was learning in the Flamingo Literacy Matrix in my classroom,” says Quirk, who teaches at Glen Springs Elementary in Alachua County.

Professor Paige Pullen, the researcher behind the matrix, says she often hears from teachers like Quirk when she attends professional development workshops to talk about the Flamingo Literacy Matrix.

“I’ll ask teachers, ‘How many of you felt when you first graduated that you were prepared to teach reading?’” Pullen says. “No one raises their hand.”

With the Flamingo Literacy Matrix, teachers can get a major boost in their skills. In 2019-2020, 9% of teachers who signed up demonstrated mastery of literacy content on a pre-test. After they finished, 98% demonstrated mastery on a post-test.

Pullen says her desire to use research to help teachers comes from her own experience. Between her master’s and doctoral programs at the UF College of Education, Pullen taught elementary school for 12 years. When she was asked to work with struggling readers, she realized she was not prepared.

“At that time, children were learning to read in spite of me, not because of me,” says Pullen, the chief academic officer of the Lastinger Center.

She began her Ph.D. research and a deep dive into the science of reading and discovered ways to demystify the process of teaching children to read.

Reading Wars

Since the 1980s, educators have debated the merits of reading programs, with whole language approaches on one end of the spectrum and phonics-based approaches on the other.

Whole language approaches emphasize putting books in children’s hands and teaching them to read by recognizing words in text and using other clues, such as pictures.

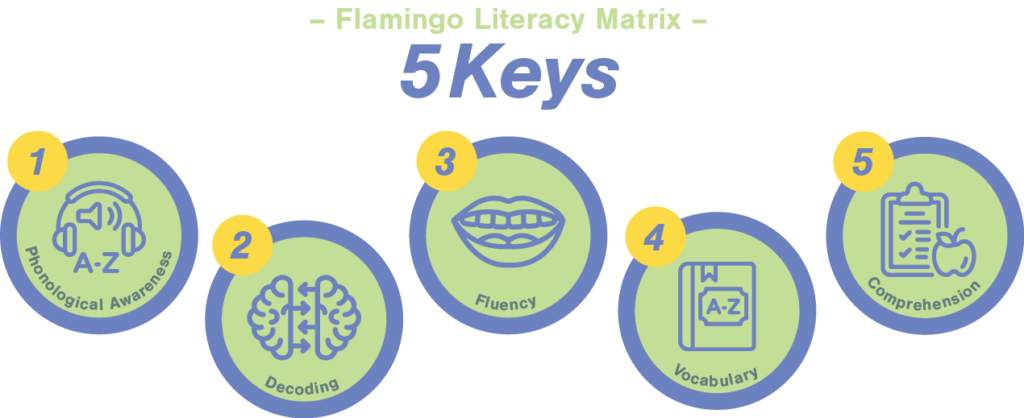

While access to books is still important, over the last 30 years, the science of reading has shown educators that helping children learn to read requires a systematic approach that recognizes key components:

- Phonological awareness, or recognition of individual sounds in words

- Decoding, or sounding out unfamiliar words

- Fluency, the ability to read with speed and accuracy

- Vocabulary

- Comprehension

For each area, the Flamingo Literacy Matrix provides strategies to assess and instruct a child as well as strategies on how to intervene when a child struggles. The program is online, so accessible from anywhere. The program meets the requirements for the Florida reading endorsement, and South Carolina recently adopted it as part of the state’s Read to Succeed program. Other states are interested as well.

The matrix also allows teachers to upload a video of their teaching practices and get feedback.

“Can they translate the research into practice?” Pullen asks. “We’re teaching them the research, the evidence-based practices, behind how to teach reading.”

While the matrix boosts teacher knowledge, it also achieves the ultimate goal of helping students. Students whose teachers completed the matrix saw:

- A 65% improvement in phonological awareness.

- An 86% improvement in their decoding skills.

- A half-year boost in reading growth.

Children with phonological awareness can use the sounds of language to learn how to decode printed text. They can use phonemes, the smallest unit of sound, to understand the relationship between letters and the sounds they make. As they gain fluency, they can segment longer words and match and blend sounds to decode words.

Phonological awareness and reading gains go hand in hand.

Reading is particularly important now, as parents and teachers work to offset pandemic-related learning losses. Pullen notes that this year, only 54 percent of third graders are reading on grade level, compared to 58 percent in 2019, before the pandemic.

The spotlight is on third grade because it is a transition stage, Pullen says. After third grade, students transition from learning to read to reading to learn, making it a skill that lays the foundation for all other learning. Pullen says struggling to read can have lifelong consequences: higher high school dropout rates, lower earnings and greater rates of incarceration.

Book a Month

Pullen and her colleagues at the Lastinger Center took on another challenge this fall after the Florida Legislature passed a $200 million program called the New Worlds Reading Initiative, which was championed by House Speaker Chris Sprowls.

“We cannot overstate the profound impact teaching a child to read will have on their future success,” Sprowls said. “Not only do we open them up to new worlds and ideas, we give them the tools to expand their imagination, foster their curiosity and ultimately chart their own destiny.”

The Lastinger Center was asked to administer the program, which will put a new book each month in the hands of students from kindergarten to fifth grade who are reading below grade level. To complement the books, Pullen says the professional development resources in the Flamingo Literacy Matrix will be adapted to make modules that are easy for parents to use.

Short videos will demonstrate strategies parents can use at home to help support the development of foundational skills that go into reading.

“We’ll actually be able to implement similar strategies from the literacy matrix, but designed for parents to implement at home, and these services will be delivered with the books,” Pullen says. “This will increase the opportunity for parents and children to read together while providing foundational skills.”

By combining teacher development, access to books and parental support, the goal would be improved outcomes for students on third grade reading and beyond.

“For struggling readers, we know that we have to go beyond the school day,” Pullen says.

“If you can’t read, you are not going to be successful in math and social studies and science or any other content area,” Pullen says. “Reading holds the key and opens the door to knowledge in every other field.”

Words on a Page

For readers who struggle, words on a page are a frightening puzzle, one they lack the skills to figure out. There are clues, to be sure, like pictures on a page, but guessing a word is different than knowing it. And as school progresses, the pictures on the page become less and less common.

Pullen uses a slide in her professional development presentations that shows a phrase in other languages to demonstrate how alien text can look to a struggling reader:

Tha leughadh na obair iom-fhillte a dh ‘fheumas ioma-fho-sgilean a thoirt a-steach. Feumar na fo-sgilean sin a chuir an sàs le ìre àrd de fèin-ghluasad agus mionaideachd.

That’s Scottish Gaelic for: Reading is a complex task that requires the integration of multiple subskills. These subskills must be implemented with a high degree of accuracy and automaticity.

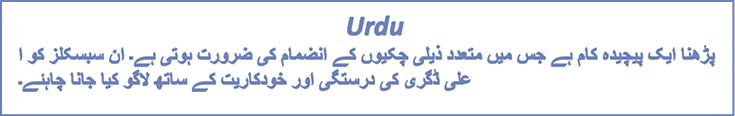

Another example Pullen uses is Urdu (see graphic), an alphabetic language that immediately puts the viewer in the position of being a non-reader.

“Suddenly, you realize the complexities of learning how to read,” Pullen says. “You have to understand the symbols. You have to understand the sounds the symbols make. You have to understand how to put those sounds together. You have to understand where one word begins and another word ends. You have to understand directionality, where do you even start reading.”

Pullen says it takes explicit systematic instruction to pull all the subskills together to learn to read. The sound system of language — where words begin and end, the sounds of letters and what the letters sound like when combined with others, and that the sounds go together to make words — is only part of the puzzle. Readers need to understand the structure of language and how language works as they build their knowledge of grammar and vocabulary and learn to discern meaning from text.

“When we think of how all these processes have to work together, we suddenly realize how complex learning to read is,” Pullen says. “We’re not going to be able to just give a child a book and expect that they will figure it out.”

The Toolbox

In her path to teaching, Quirk was a veteran of multiple teacher training seminars and kept a cheat sheet handy for the professional jargon she often encountered. Decoding the bureaucratic lingo, she said, was half the battle in getting trained.

“For me, there was a lot of technical jargon thrown about in professional development, and they expected you to just know it,” Quirk says. “I’d spend a lot of time writing down terms to look up later.”

By contrast, the Flamingo Literacy Matrix was easy and immediately usable. No decoding necessary.

“The literacy matrix didn’t assume you knew it all but also didn’t dumb it down. I think I knew I had absorbed it when I was walking home with my daughters and I remember stopping and saying, ‘Holy cow, I understand this well enough that I just explained it to my daughters.’’’

Pullen says she learned to teach reading in the 1980s using a whole language approach, so she is enthusiastic about sharing the science of reading in training the teachers of today. Raising children to be readers requires raising proficient readers, she says.

“Think about what we love and choose to do in our free time,” Pullen says. “If you’re not good at something, you’re not going to choose it. Part of the love of reading comes when we find success.”

Quirk recalls the change in her skills and the skills of her students in her 2017 kindergarten class. The literacy matrix, she says, became second nature for her, something she used every day, and it allowed her kindergartners to enter first grade with a solid foundation.

“Curriculum comes and goes,” Quirk says. “This will age well.”

Source:

Paige Pullen

Chief Academic Officer, Lastinger Center for Learning

ppullen@coe.ufl.edu

Related Websites:

Hear the Story

The audio version of this story is available on our YouTube.