Florida’s economy — so reliant on tourism — has been particularly hard hit by the pandemic. Tens of thousands of workers at theme parks, on cruise ships, at airlines, airports and the countless other businesses that support them have been laid off as international and domestic travel ground to a halt last spring.

The loss of that business directly affected Florida’s next biggest industry — agriculture — as farmers lost some of their biggest customers, the restaurants in those parks and on those ships.

UF researchers across campus quickly turned their expertise to understanding the economic impact of the pandemic, and to developing ways to mitigate losses now and in the future.

Tourism Upended

Travelers have gone through several stages of concern as the pandemic grew, then waned, then grew again, according to a series of 30 surveys totaling more than 22,000 people by UF’s Tourism Crisis Management Initiative.

The survey has been conducted weekly since the beginning of the year, and while initial concerns focused on avoidance of international travel, then domestic travel, by October the surveys showed people were either avoiding travel altogether or making sure they have contingencies, said Lori Pennington-Gray, director of the initiative and a professor in UF’s College of Health and Human Performance.

“Travel anxiety is linked to stages that are occurring in the progress of the virus,” Pennington-Gray said. “When we as a nation were in lock down, the travel anxiety was at its highest. As we saw cases starting to decline, we saw travel anxiety decrease. As of the most recent data collection, we see that travel anxiety is increasing again as we climb in the number of cases nationally.”

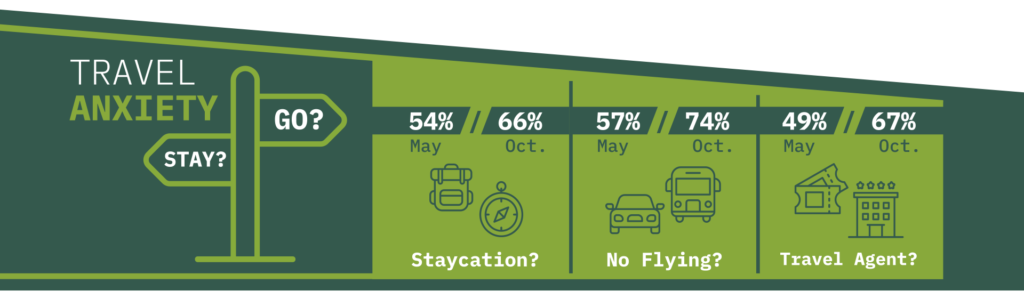

In mid-October, more than 66% of respondents said they were more likely to take a staycation than in the past, up from 54% in May.

“Staycations are more than just staying home and not traveling,” Pennington-Gray said. “They are engaging in travel closer to home, participating in day trips and drive tourism. As one would expect, this type of travel is at a higher level than ever.”

Over 74% of the October respondents said they were more likely to take a trip that doesn’t require flying, up from 57% in May.

“Drive tourism has been a type of travel that we have seen in the past. It was a response to 9/11, the 2008 global recession and now COVID-19,” Pennington-Gray said. “We are typically seeing shorter trips, but there are also a growing number of people who are buying RVs, camping, taking longer trips and exploring our parks.”

When people do travel, more said they would get travel insurance and use a travel agent.

“As we saw at the outbreak of the pandemic, many travelers were stranded in foreign countries or on cruise ships,” Pennington-Gray said. “U.S. travelers are aware that this pandemic is fluid and that things are still continually changing. They are more aware of the need for travel insurance to help with itinerary changes, evacuation or other needs that may arise due to a change in government policy during their trip.”

She added that in addition to a growing interest in travel insurance, “we are seeing the growing need for a travel agent to help to coordinate the entire travel itinerary, particularly in the case of a change due to increased cases and potential closing of borders.”

More than 67% said they were more likely to use a travel agent, up from 49% in May.

Travelers are also holding travel companies to a higher standard when deciding which company to use.

“The U.S. travel market expects more safety precautions than ever from the travel industry. Travelers are looking at websites for information, making sure that there are policies surrounding social distancing, wearing masks and sanitization practices,” Pennington-Gray said. “We think this is the new normal and that these expectations of safety are here to stay. Although the context of safety may change, the responsibility of the industry to provide information to the consumer will not.”

Agricultural Angst

More than 70% of Florida’s large farms sell to the service industry, which includes theme parks, hotels, restaurants and cruise lines, so when COVID-19 brought the tourism industry to a crashing halt last spring, farmers around the state were left with millions of pounds of fruits and vegetables that were at peak harvest.

Florida farms took losses that are hard to comprehend. One grower plowed under 2 million pounds of green beans and 5 million pounds of cabbage because there was nowhere to send the produce before it spoiled. Another farm dumped 100,000 pounds of tomatoes in one week.

“COVID-19 hit these growers at the worst possible time,” said Catherine Campbell, a UF/IFAS assistant professor of community food systems. “It was our peak harvest season, and the market fell out. Florida supplies most of the produce east of the Mississippi River in the spring and it all just stopped. It was bad for everyone, but producers in other parts of the country were at planting time, not harvest time. For our producers, they had already reached the maximum investment on those crops — paid to plant, maintain (spray, irrigate, fertilize, etc.) and in many cases they already harvested crops — then they couldn’t sell them.”

While the losses were huge, UF/IFAS experts, industry groups, and state and regional organizations such as the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services and the Florida Farm Bureau Federation developed a variety of programs and resources to connect Florida growers to buyers.

Retailers around the state committed to purchasing more Florida and U.S.-grown produce, but farmers also marketed direct to consumers. One packing house in Homestead opened on weekends for consumer sales and sold more than 120,000 pounds of vegetables.

“This event was a ‘cue to action’ to develop support systems that make it possible for producers to make these kinds of changes in market channels. Their profits were probably not even close to breaking even, but at least it’s a help.”

Despite substantial losses, producers also harvested and transported produce to food banks and other hunger-relief organizations to meet the increased demand from those in the community who were unemployed.

“These programs can help producers, large and small, find buyers when their traditional supply chain breaks down,” Campbell said. “The hope is that this strategy will provide a foundation to support food system resilience in the event of future public health emergencies and natural disasters. It can also help move product instead of it going to waste. If we know where there is food and where people need it, we can mobilize it and get it to those in need.”

Consumer Confidence

Florida’s Consumer Confidence Survey, conducted monthly by UF’s Bureau of Economic and Business Research (BEBR), was at a 20-year high of 102 in February, but it plummeted a record 13.5 points in March as coronavirus caused business in many of Florida’s most important industries to slow or shut down entirely.

“The decline in consumer confidence was fueled by growing pessimism … due to the economic damage brought by the coronavirus outbreak,” said Hector H. Sandoval, director of BEBR’s Economic Analysis Program.

Confidence clawed its way back in fits and starts throughout the summer, but by September it had only regained half of what was lost in March.

The index used is benchmarked to 1966, which means a value of 100 represents the same level of confidence for that year. The lowest index possible is a 2, the highest is 150.

Tory Moore, Perry Leibowitz and Joseph Kays contributed to this article.