A team of researchers at the University of Florida has developed a system powered by solar energy that uses artificial intelligence to ultimately decrease the cost of keeping essential home appliances or devices running through a power outage.

That kind of system would come in handy or even save lives during hurricanes and natural disasters when people can spend days — sometimes weeks — without power, in sweltering homes while food spoils in the fridge.

Ultimately, the system would provide, at a lower cost, energy resilience to hurricanes and natural disasters, which have become a more common issue in the face of climate change, said Prabir Barooah, Ph.D., a professor at the Herbert Wertheim College of Engineering’s Department of Mechanical & Aerospace Engineering and one of the researchers on the team.

“Our energy infrastructure needs to be sustainable, and it is not at present,” Barooah said. “‘Smart’ is a way of achieving that sustainability. Without the ‘smart-ness,’ our energy infrastructure cannot handle renewable energy.”

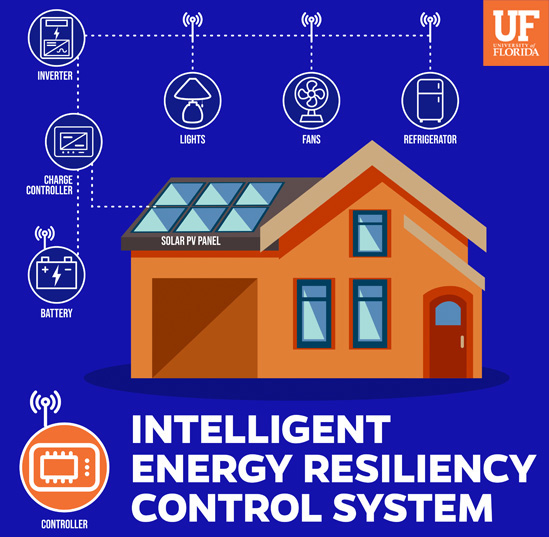

The Intelligent Control System

When a hurricane barrels toward a community, most people brace for damaging winds and flash flooding. Yet, most of the time, the immediate destruction of the wind and rain event is short-lived. The indirect effects, however, like the loss of electricity, can be life-threatening.

But powering a home during an outage is expensive, and fuel might be difficult to find during the aftermath of a hurricane. A rooftop solar system with a battery could provide a better option since the sky is often clear right after a hurricane. But a large number of solar panels and a large battery is needed to provide full backup.

The system developed by the team — which includes Barooah, Sean Meyn, Ph.D., at the Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, and graduate students Naren Raman and Ninad Gaikwad at the Department of Mechanical & Aerospace Engineering — would eliminate the need to seek fuel. And, if the researchers achieve their goal, it would also be more economical.

“My goal is to have a positive impact on everyone — and especially on the economically disadvantaged,” Barooah said.

To work toward that goal, Barooah and the team decreased the number of solar panels needed to supply power to a house to about three (a typical home needs 20 to 25 solar panels to generate enough electricity for the whole house).

Also, the battery, which is not in use 99% of the time, needed to be smaller and more affordable.

Finally, he and the team had to address how to keep the battery powered even when there are clouds.

That’s where the team’s Intelligent Control System comes into play.

The system would determine how much power and what appliances receive electricity throughout the outage. It would send a wireless signal to receivers connected to designated outlets to turn on or off power as needed. The cost of the additional electronics is under $300.

For example, if it’s running low on power reserves from the previous night and it knows it has a small window of sun, the system may choose to fast charge the battery.

“Also, the Intelligent Control System can determine what it can power with the amount of energy it has left,” Barooah said. “It can predict, ‘I cannot power the refrigerator, the fans and the lights, or three hours from now I will have zero energy’. It can make the decision to only power the fridge since that is the most critical appliance.”

Additionally, if it knows that it’s going to be cloudy during the afternoon, it may cut off certain devices or appliances, to prioritize others. And it can make those decisions in a fraction of a second, Barooah said.

There’s a catch, however, which the team is still working to address.

Though they have worked aggressively to cut down on the cost of the system to make it economically feasible, the installation of the solar panels — whether it’s three or 30 — is still a costly barrier, requiring electrical rewiring as well as checks and inspections.

If the team can decrease the cost of installation, it can move on to the next phase: seeing it in as many homes as possible.

“The ultimate goal with this particular system is to have it widely adopted so that no one struggles after a storm, even if the outage lasts a long time,” Barooah said.

This story originally appeared on UF News.

Check out other stories on the UF AI Initiative.