Lay people who participate in citizen science develop more interest in science after participating in such a project, a new University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences study shows.

“Participating in science does more than teach people about science,” said Andrea Lucky, an assistant research scientist in the UF/IFAS entomology department and co-author of the study. “It builds trust in science and helps people understand what scientific research is all about.”

Tyler Vitone, a master’s student in Lucky’s lab in the entomology and nematology department, and his co-authors wanted to understand what participants take away from the experience of being part of a citizen science research project. To do this, they looked at a group of people who had limited experience with scientific research: students in an introductory entomology course called The Insects. The course is for non-science majors and meets a biology general education requirement for students across campus, so it includes students with a diverse mix of interests, from art, English and history to finance, marketing and political science. The research team conducted assessments in the fall and spring semesters, from 2013 through 2015.

As part of the course, students must participate in one of two citizen science projects coordinated by Lucky: One is called the School of Ants (www.schoolofants.org); the other, Backyard Bark Beetles (www.backyardbarkbeetles.org).

Both projects involve collecting insects to map and monitor species distributions. The School of Ants project invites participants to collect ants near a home, school or work by placing crumbled cookies on an index card in two types of environments: a paved surface such as a driveway or sidewalk, and a green space such as a lawn or garden. Participants record data about collection location, collect and freeze the ant specimens overnight, and then deliver them in person or by mail to Lucky’s laboratory at UF.

Participants in the Backyard Bark Beetles project follow instructions to make a simple beetle collection trap using a 2-liter bottle baited with ethanol-based hand sanitizer. Participants hang the trap for 24 to 48 hours, then collect the trapped beetles into a zip-top bag and deliver them to Lucky’s lab.

Once the insects have been identified, the participants learn about the species they collected. These samples collected by project participants have led to a better understanding of where ant and beetle species can be found. This is especially important in the case of dangerous or economically damaging introduced species whose ranges are expanding, Lucky said. Similar to citizen science projects nationwide, UF/IFAS scientists work in partnership with the public to address real-world problems.

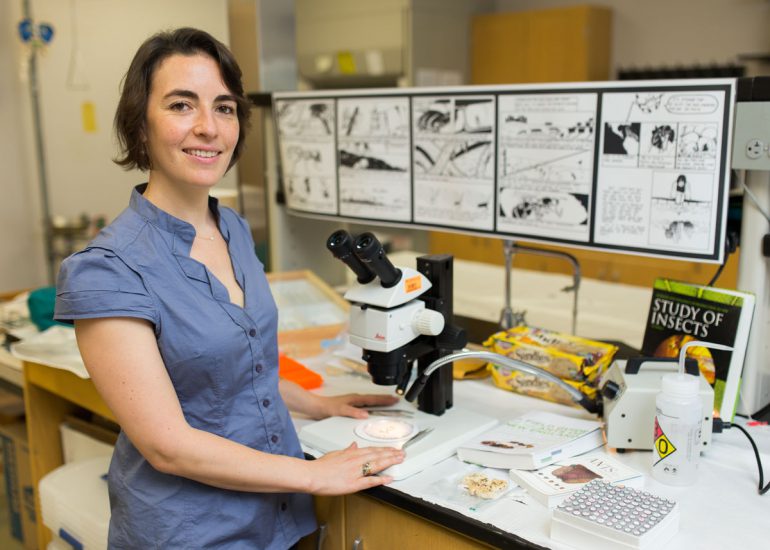

Lucky has been leading — and continues to coordinate — citizen science projects from her UF/IFAS lab.

For this study, in order to understand how citizen science affected both knowledge and attitudes, the research team took a mixed-methods approach that took into account what people learned as well as how their perceptions of science changed. Both before and after students participated in one of the two projects, the research team surveyed how much students knew about insects and assessed their attitudes toward science. After their citizen science experience, students were asked open-ended questions about these topics.

For the quantitative data, 74 students responded to questions about their perception of the value of science how much they trust it and their level of interest in conducting research. They responded with answers in five categories ranging from “low” to “high.” At the end of the course, students were also asked to consider how their perceptions changed over time. Researchers found that not only were students significantly more interested in and trusting of science, they were significantly more interested in conducting research in the future. This pattern was especially strong when students evaluated their own changes in attitude.

These results were echoed by students’ responses to open-ended questions about citizen science; the majority of students were excited to “get inside” the process of doing science, even if they didn’t want to be scientists themselves, UF/IFAS researcher said.

Katie Stofer, a UF/IFAS research assistant professor of agricultural education and communication and a study co-author, said UF/IFAS is full of examples of citizen science or volunteer monitoring programs.

“These projects are often thought of as primarily benefiting professional scientists or ‘science’ by helping professionals collect data over space and time, which they couldn’t do alone,” Stofer said. “However, it’s really a win-win for everyone involved. As we found in the paper, non-professionals can get a better idea of how professional science is done, even when they participate in what might be considered a small project.”

“The fact that these programs help UF/IFAS professionals do research better is a bonus in addition to the impact of engaging non-professionals in science research,” she said.

The study will be published in the January issue of the open-access Journal of Science Communication.