We’ve heard a lot about coronaviruses in the past year, after the sudden emergence of the COVID-19 global pandemic. But coronaviruses are a diverse group of viruses known to infect most mammals, some birds, and even a few amphibians

Conventional wisdom holds that only a few strains of the Coronaviridae family infect people, but new research may turn this dogma on its head.

According to new work by a group of University of Florida and Haitian researchers, coronaviruses may spillover from animals into people more frequently than previously understood. The manuscript is available on the medRvix preprint server.

The good news is that most infections are not serious and rarely lead to person-to-person transmission, says the study’s senior author, UF Emerging Pathogens Institute Director J. Glenn Morris, Jr., M.D., M.P.H. & T.M.

“What we’ve shown is that there is likely some movement back and forth with coronaviruses between animals and people,” Dr. Morris says. “It’s simply not detected because we don’t look for it.”

And, because most leaps may not move past their human host.

Different kinds of coronaviruses

Scientists organize the coronavirus family, Coronaviridae, into four genera (which are subgroups within a taxonomic family): Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus, Deltacoronavirus and Gammacoronavirus.

Until now, only seven viruses in the alpha- and betacoronavirus groups were known to infect people. Four of these cause common colds. The other three emerged in the last few decades; all fall within the betacoronavirus group, and all cause serious and sometimes fatal respiratory diseases — Middle East respiratory syndrome, severe acute respiratory syndrome and COVID-19.

Traditionally, it was thought that delta- and gammacoronaviruses only infected nonhuman animals. But this barrier is more porous than we realized.

First known deltacoronavirus in humans

The researchers detected, for the first time, a deltacoronavirus in humans. More specifically, they found the porcine deltacoronavirus —called PDCoV, it is known to infect pigs — in blood samples of several Haitian children.

“This challenges the basic concept that there are only a few coronaviruses capable of infecting people,” Dr. Morris says.

But, he’s quick to add, this is not likely the start of a new pandemic. Rather, it reveals what may be regular but isolated movements of coronaviruses into people which goes largely unnoticed.

Samples from the children also revealed two different genetic PDCoV strains. One strain closely matched sequences known from epidemics of PDCoV in pigs in China. The other closely matched sequences known from PDCoV epidemics in pigs in the United States.

The two strains indicate that the virus was introduced separately on two different occasions into Haiti, probably into pig populations, Dr. Morris says.

Monitoring school children in Haiti

The new insights come from a health monitoring program involving school children in Haiti’s Gressier region. The blood-based infectious disease monitoring study began in the aftermath of the Haitian earthquakes and the subsequent spread of cholera. When the participating children come to their schools’ clinic with fevers, but no other symptoms linked to an obvious known illness, clinicians ask to obtain a blood sample for testing. The children’s parents consented to the research and blood is only drawn when the children agree. The program has previously uncovered some unusual pathogens including Mayaro and Madariaga viruses and has also identified several of the known human coronaviruses associated with common colds.

Blood plasma samples from the children, aged 5 to 10, were collected in 2014 to 205 when they experienced fevers but no clear symptoms linked to illnesses. The children recovered from their fevers, and at the time the researchers were unable to identify a cause.

“But the problem with a lot of diagnostic tests is that they assume you know what you are looking for,” Dr. Morris says. “You have to culture the blood samples, which is difficult and rarely done nowadays, to discover unknowns.”

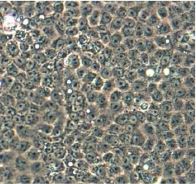

It was not until the current pandemic that the research team went back and reevaluated some of the samples looking for an unknown virus as a possible cause. Using laboratory techniques that inoculate cell culture with human plasma samples, the team observed changes in the cells consistent with infection caused by a virus. They then sequenced the viruses and determined that they were coronaviruses similar to deltacoronaviruses found in pigs.

Detecting the unknown

The study’s first author, John Lednicky, who is a research professor in the department of environmental and global health in UF’s College of Public Health & Health Professions, says that the research team thought outside the box to overcome the challenge of testing for an unknown.

“Traditional PCR technology is guided by a dogmatic view that ‘if you look, you find,’” Lednicky says. “But we merged classic virology with molecular approaches. My laboratory does this frequently, and we continually find viruses that were overlooked by standard tests.”

Polymerase chain reaction technology (PCR testing) is virus-specific and assumes that investigators know in advance what they are looking for. One example of this is getting a COVID-19 test. The gold-standard PCR-based tests target the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 and look for its genetic signature in each sample.

But today if investigators aren’t sure what virus they may find, they must think differently. Lednicky has expertise in using next-generation sequencing methods to reveal the pathogen’s identity, an uncommon step that most research labs don’t pursue due to time and expense.

What does this mean?

Both PDCoV strains found in the Haitian children contained identical genetic mutations in areas related to the spike protein which enables the virus to enter human cells. This means that nature figured out the exact same trick, independently, twice.

“It’s a nice example of convergent evolution,” Dr. Morris says. “Both strains underwent the necessary evolutionary changes to infect people. This is probably happening all the time. We’ve been lucky in that there have not been many outbreaks until the recent COVID-19 pandemic.”

Coronaviruses are very sensitive to adaptive forces that select for mutations that allow them to infect people, the researchers write.

“We don’t think this virus will take over the world, it’s not likely the next pandemic,” Dr. Morris says. “But this does provide some idea as to the readiness of coronaviruses to gain mutations that let them infect us.”

When the current COVID-19 epidemic is taken in the context of the preceding SARS and MERS epidemics, it shows that coronaviruses are a clear cause for public health concern. But the new research also places these more serious diseases in a broader context.

“Coronaviruses are very common in the animal world,” Dr. Morris says. “What our observations say, is that they probably move into human populations periodically, it’s just that most probably lack the critical genes to cause serious illness.”

Which is cautiously good news, for now, as researchers illuminate more about how these viruses move between animals and people.

This story originally appeared on UF Emerging Pathogens Institute.

Check out stories about UF research on COVID-19.