Although direct payments to Americans have been utilized during previous economically challenging times – the last as part of the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 – never before had the world looked as it had in the spring of 2020, when the start of the coronavirus pandemic convened a number of unusual circumstances all at once.

By late March, with an anticipated economic stimulus package expected to include direct payments to citizens, a University of Florida food and resource economist wondered: How would this money be spent?

“It’s already a rare occasion, effectively like money falling from the sky,” said John Lai, an assistant professor of agribusiness in the UF/IFAS food and resource economics (FRE) department. “We were curious, with everything going on, what people would prioritize.”To answer the question, Lai and a team of his FRE colleagues deployed a nationwide survey in mid-May, shortly after the payments approved in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act started to appear in citizens’ bank accounts.

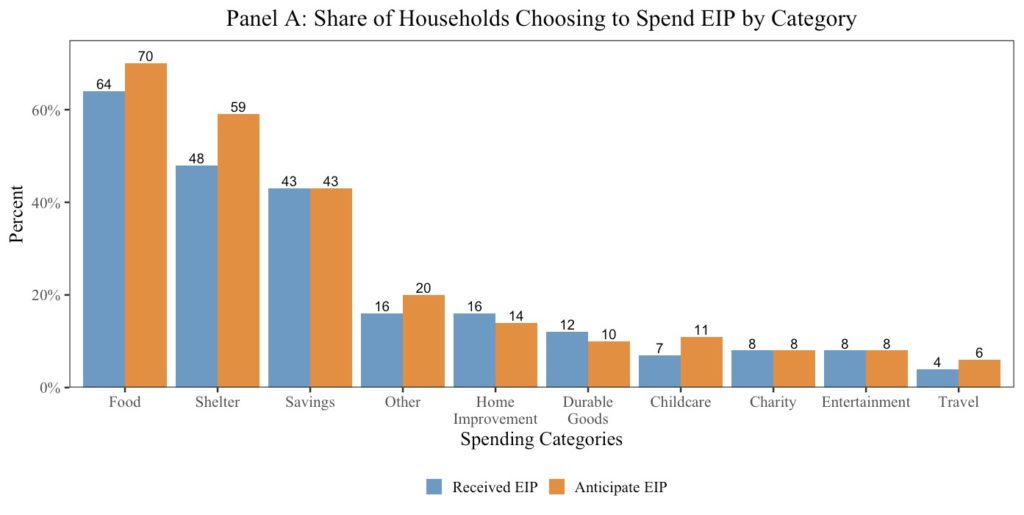

Most of the 972 respondents — a representative sample of the national population — had or planned to put the money toward food (average of 67%) and housing (average of 53.5%) needs. Most of the findings were fairly consistent when comparing those who had already received the payment and those who anticipated receiving it.

“More surprisingly,” Lai noted, “we found that the third-highest allocation was marked for savings, with people likely deciding to shore up emergency funds in the midst of all of the uncertainty.”

The findings are important now as Congress continues to debate future stimulus options and industries have come away with lessons learned regarding supply chain and other pandemic-driven adaptations.

The survey asked respondents to indicate how they spent or planned to allocate the money among 10 categories – charity, childcare, durable goods, entertainment, food, home improvement, savings, shelter, travel and “other.”

“A third of our respondents indicated their income fell due to COVID,” said Stephen Morgan, an assistant FRE professor who was part of the survey team. “So while it wasn’t surprising that people put the money toward immediate needs, it was surprising how large the share was that went toward food.”

Outside of the top three categories, the remaining categories each averaged less than 20% of respondents’ allocations.

Respondents were further asked to specify changes in their food purchasing behavior, both in the types of stores and in the food choices they were making.

“We found that people increased spending the most on shelf-stable products, like dry and canned foods, and they bought less of the pre-prepared foods,” Morgan said.

Both this finding and a reported increase in shopping at grocery stores, the researchers note, are important for sectors like agricultural producers to have identified, as many had to adjust to supply chain issues and other complications early in the pandemic.

Fast food sources, on the other hand, saw the biggest decline, which Morgan said was in line with closures that may have still been ongoing at the time.

“But convenience stores also saw a decline,” Morgan said, explaining that the exact cause for that could not be determined. “It may speak to the decline in people seeking out pre-prepared foods, the fact that people weren’t traveling, or even perceived risk factors.”

The full report, including charts and data, appear now in a new article in Choices Magazine, a peer-reviewed publication of the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association.

This story originally appeared on UF/IFAS Blogs.

Check out stories about UF research on COVID-19.