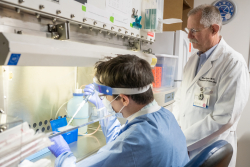

University of Florida Health researcher Mark Brantly, M.D., and his team are working to evaluate a drug treatment for the novel coronavirus that might block the deadly inflammatory response caused by the disease that curtails the lungs’ ability to function.

In the absence of any known therapies for COVID-19, Brantly wanted to open a clinical trial on severely ill patients with respiratory distress to see if the treatment works.

First, though, he needed approval from UF Health’s Institutional Review Board. This committee of 21 physicians, nurses, pharmacists, researchers and community members oversees all clinical trial protocols. This ensures all federal, state and local rules and guidelines meant to protect patients’ rights and safety are followed.

Under normal circumstances, an IRB review can be a slow process with thousands of other studies in line in what is a first-come, first-serve undertaking. In some cases, it can take a couple of months for approval.

Brantly’s approval came in four days.

“It was really done in record time,” said Brantly, a professor in the UF College of Medicine’s division of pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine and the department of molecular genetics and microbiology. “That is the fastest I’ve seen it done in my career.”

This isn’t happenstance. It’s by design.

Amid the worst public health emergency in a lifetime, UF Health leaders have taken steps to speed novel coronavirus research, recognizing the urgent need to provide answers and options to the communities they serve. There are two key components of this effort: IRB retooled its approval process for coronavirus trials, and the UF Clinical and Translational Science Institute, or CTSI, set up a $2 million pilot research fund for scientists with translational projects that can be rapidly mobilized.

These rapid-response pathways are intended to quickly facilitate COVID-19 clinical trials.

“UF Health researchers are working tirelessly on innovative approaches to combating the novel coronavirus,” said David R. Nelson, M.D., senior vice president for health affairs at UF and president of UF Health.

“We need to better understand the virus, search for new treatments and bring them from the bench to the bedside as rapidly and safely as possible,” he added. “To that end, we want to provide all the support we can to our scientists and staff to promote a rapid response to a health emergency unrivaled in modern times.”

At any one time, hundreds of study protocols might be in the pipeline for IRB review. So, the board is streamlining the approval process by putting coronavirus research to the front of the line, without sacrificing proper regulatory review or patient safety.

“It’s like when you go to Disney World,” said Peter Iafrate, Pharm.D., chair of the IRB for UF Health since 1996. “If you stand in line, you can be there for two hours. If you have the right pass, you get right on. No matter how long you wait, the ride you get is the same. Once the IRB reviews the study, no shortcuts are taken.”

The full IRB is now meeting weekly via Zoom, rather than its traditional biweekly schedule, said Iafrate. He is now spending up to 80% of his time reviewing COVID-19 projects.

Iafrate said it is important to note that all safeguards are still in place. A COVID-19 project must still check all the boxes and provide all patient protections. This disease presents some unique safety issues not only for the patient, but for the scientists who might themselves be exposed to the coronavirus through the research.

CTSI’s funding efforts are especially crucial for researchers. The institute accepted applications April 1 through April 30, providing a rapid turnaround for grant approval.

In the world of science, grant proposals and funding awards are often many months, even years in the making. That obviously won’t do in a pandemic.

Duane A. Mitchell, M.D., Ph.D, CTSI director and assistant vice president for research and associate dean for translational science and clinical research, said CTSI funding serves as a bridge until extramural funding becomes available.

“These pilot awards are designed to support initiatives that will have a near-term impact within the next six months on efforts that will either allow for the diagnosis, prevention or the treatment of COVID-19 disease, or the SARS-2 virus,” Mitchell said. “We accepted applications with a very rapid turnaround for funding decisions really from all avenues of behavioral, social, biological or medical and clinical research.’’

Awards are capped at $100,000 each. The funding program is administered by CTSI with support from UF’s “Creating the Healthiest Generation” Moonshot initiative, UF Health and the UF College of Medicine.

UF Health pediatric oncologist Elias Sayour, M.D., Ph.D., received a $100,000 grant from CTSI to develop a vaccine for COVID-19 by adapting a vaccine formulated for cancer in his lab over the last several years. This CTSI award is co-sponsored by the UF Health Cancer Center.

The cancer vaccine, a novel form of immunotherapy, is slated to be tested to treat malignant brain tumors starting this summer in a long-planned, U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved clinical trial. Sayour’s lab now will simultaneously begin to investigate ways to translate and test the method in preclinical studies for COVID-19.

Sayour’s cancer vaccine method attempts to “educate” the immune system that a tumor is foreign by surgically removing the tumor, extracting genetic material called RNA and then encasing the RNA in biocompatible lipid nanoparticles. When reinjected into the patient, the nanoparticles make the cancer look to the body like a dangerous virus, activating the immune system, Sayour said.

“We can make synthetic RNAs that encode for COVID-19’s spike protein since the sequences are known,” said Sayour, an assistant professor of neurosurgery and pediatrics and principal investigator of the RNA Engineering Laboratory within the Preston A. Wells, Jr. Center for Brain Tumor Therapy and UF Brain Tumor Immunotherapy Program.

What everyone working on COVID-19 research has in common is unusually long hours.

“There’s not really a weekend anymore,” Iafrate said.

This story originally appeared on UF Health.