Shark attack numbers have sunk to dramatic lows, likely a side effect of closed beaches and widespread quarantines, according to experts at the University of Florida’s International Shark Attack File.

Only 18 unprovoked shark bites have been confirmed globally from Jan. 1 to June 18, down from 24 over the same time period in 2019 and 28 in 2018. Seven of this year’s bites occurred in the U.S., two in Florida waters. Three unprovoked attacks resulted in fatalities, two in Australia and one in California, an increase from last year’s total of two deaths.

The ISAF experts have noted an unusual decrease in bites in recent years, with 2019’s 64 unprovoked attacks representing a 22% drop from the most recent five-year average of 82 incidents annually. But this spring and early summer’s numbers are an even more significant dip in the downward trend, said Tyler Bowling, manager of the ISAF.

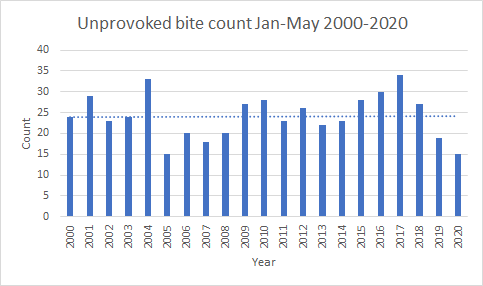

In a 20-year comparison of bites, 2020 ties 2005 for the lowest number recorded from January through May, with 15 unprovoked attacks, compared with an average of about 25.

“The fact that we’re in the teens at this time of year, with only two bites in Florida, is a sign that something else is at play,” Bowling said. “COVID-19 is the obvious answer, though there could be other factors.”

Bowling and Gavin Naylor, director of the Florida Museum of Natural History’s shark research program, investigate all human-shark interactions, with a focus on bites initiated by a shark in its natural habitat with no human provocation.

Florida, which annually tops the global shark attack leaderboard, had tallied eight bites by mid-June in 2019 and seven in 2018. This year, experts have confirmed two minor bites in the state thus far, one each in Duval and Brevard counties.

Two bites also occurred in Hawaii, with single bites in California, Delaware and North Carolina.

“The East Coast has been pretty quiet, and that’s where we pick up blacktips and the occasional bull shark,” Bowling said.

A few additional incidents remain under investigation, and bites can change classification as more information becomes available, he said.

Many Florida beaches, parks and boat ramps were closed during parts of March, April and May, with restrictions still in place in certain counties on activities such as sunbathing, beach-access parking and number of visitors.

Capt. Tamra Malphurs, public information officer for the Volusia County Beach Safety Ocean Rescue, said the county’s beaches, which closed for one day in April, experienced fewer visitors during typical peak times such as Spring Break, and the usual flood of tourists slowed to a trickle. But the pandemic has not deterred one particular group of beach-goers.

“We haven’t seen fewer surfers,” she said.

While shark attacks are down, swimmers and surfers should not lower their guard, Bowling said. Bite numbers tend to surge in July, the height of vacation season, and in September, the month that marks the beginning of the annual blacktip shark migration from the Carolinas to South Florida.

While the chances of being bitten by a shark are minimal, the ISAF offers recommendations on how to lower the risk of a shark attack or fend off an attacking shark. Vigilance on deserted beaches is especially important, Bowling said, advising surfers to have a first aid kit and tourniquet on hand.

“The buddy system is always key,” he said. “You should always have someone with you or let someone know where you’re going and when you expect to return.”

This story originally appeared on the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Check out stories about UF research on COVID-19.