As the world’s focus shifts from COVID-19 vaccine creation to distribution, researchers and clinicians continue to search for ways to alleviate the suffering of patients and the demands on crowded hospitals. Now, after Emergency Use Authorization approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, University of Florida Health is the first in the Southeast to implant a novel diaphragmatic neurostimulator in a coronavirus patient requiring a ventilator. This is the third instance of this here in the United States.

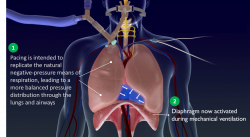

With the temporary transvenous diaphragmatic neurostimulator, a central line goes into a vein under the patient’s left collarbone. It contains electrodes that stimulate the phrenic nerves responsible for spurring the diaphragm to contract. This creates negative pressure ventilation, helping to mimic a more natural way of breathing in tandem with the positive pressure caused by the ventilator, explained Ali Ataya, M.D., an assistant professor within the UF College of Medicine’s division of pulmonary, critical care & sleep medicine.

“Although there are some diaphragmatic pacers already available, they are all surgically placed, and not feasible to use in this population,” Ataya said. “But this uses a temporary central line, like any that the patient would get, so it is much less invasive and easily performed at bedside.”

Thus far, Ataya said, the results have been promising.

“This can improve the inspiratory pressure generated by the diaphragm by almost 250%,” he said. “If this works the way we hope it does, the patient will potentially come off the ventilator sooner than predicted, and with a smoother recovery.”

After one week of using the diaphragmatic pacer, the patient came off the ventilator.

Many COVID-19 patients who contract the virus and require hospitalization are not able to breathe on their own and need to be intubated. For some, this may be for a couple of weeks; others for several months.

But ventilators are like respiratory quicksand — getting in is easy; getting out, however, is another story.

“When we discuss artificial ventilation, we often explain that the vent is giving your body time and body to heal while the machine does the work,” said Erin Silverman, Ph.D., a clinical research assistant in the division of pulmonary and critical care and sleep medicine. “But that neglects the reality of artificial ventilation. From the second someone is placed on mechanical ventilation, their diaphragm muscles begin to atrophy.”

The diaphragmatic pacemaker helps prevent the muscles from “forgetting” how to breathe on their own, and strengthens them after they’ve been weakened by critical illness, steroids, paralytics and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

In the long run, lack of diaphragmatic muscle atrophy also means patients are less likely to linger on a ventilator and require reintubation, freeing up precious bed space and equipment.

“Due to the pandemic, we’ve seen a surge in need for mechanical ventilators and ICU beds alike,” said Ataya. “The toll on hospitals and staff is unparalleled to any time before. We needed a way for patients to be able to come off the ventilator sooner, heal better and allocate space to others in need.”

A second COVID-19 patient requiring ventilation has begun to use the pacer.

“These are patients where we’ve walked that line for a long time, and it’s starting to look like they may not come off the ventilator,” Silverman said. “There’s a cycle of extubating, intubating, extubating, intubating and so on. At that point, something like this device is not even an option, so much as a necessity.”

Media contact: Ken Garcia at kdgarcia@ufl.edu or 352-273-9799.

This story originally appeared on UF Health.

Check out more stories about UF research on COVID-19.