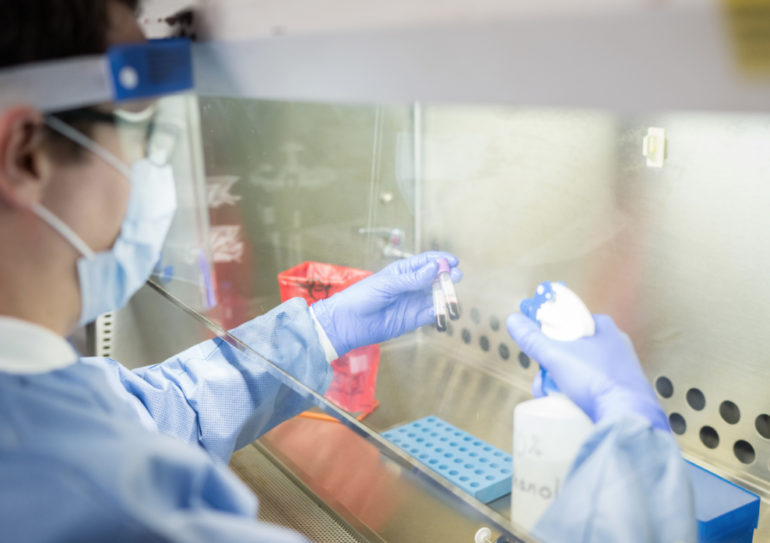

University of Florida Health has enrolled its first patient in a clinical trial for the Regeneron Pharmaceuticals’ monoclonal antibody cocktail to treat COVID-19, a therapy that might neutralize the coronavirus and prevent it from infecting cells.

UF Health is one of hundreds of medical centers internationally participating in the blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial to determine if these synthetic antibodies can lessen the severity of coronavirus infection, shorten hospitalizations and reduce mortality.

Mark L. Brantly, M.D., principal investigator of the trial at UF Health, said researchers also are attempting to calibrate the most effective dosage for patients.

Brantly said researchers across UF Health are working furiously to find treatments for COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. They are all too mindful of the lives lost to the disease.

“It’s just heartbreaking to see this happen to our family members and our friends,” said Brantly, a professor in the UF College of Medicine’s division of pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine and the department of molecular genetics and microbiology. “We’re doing everything we can to find useful treatments.”

Such randomized trials are the gold standard in clinical research, and findings from such work offer the best opportunity to reveal a treatment’s effectiveness. Blinded testing means patients do not know if they receive the drug or a placebo.

UF Health hopes to enroll at least 20 hospitalized patients who are intermediately sick or progressing to a critically ill state. Combined with other medical centers, total enrollment is hoped to reach 2,970 patients during this Phase II trial.

Brantly said it is important to note that monoclonal antibodies, if they are effective, will not eliminate the disease.

“It’s a potential treatment,” he said, “not a cure.”

The trial involves what are essentially designer antibodies. Antibodies are blood proteins that serve as one of the body’s front-line defenses against foreign pathogens, such as viruses and bacteria.

They can battle invaders in several ways. For Regeneron’s cocktail, it is hoped that the antibodies can bind to the spike proteins on the coronavirus and, like a house key unable to enter a lock because it’s wrapped in a wet piece of chewing gum, prevent the virus from entering susceptible cells.

“These are specific areas on the spike protein that bind to areas of the cell surface membrane and sort of ring the doorbell so that the cell lets the virus in,” Brantly said.

Regeneron has developed two lines of synthetic antibodies that, through testing in humans and animal models, have shown the most promise in being able to neutralize the virus. One line comes from laboratory mice whose immune systems have been genetically modified to mimic a human’s. The second line is derived from humans who have previously been infected by COVID-19.

Developing two antibodies, each targeting a different area of the coronavirus, increases the odds that the cocktail might still be effective if the virus mutates slightly.

It’s not a new therapy. Monoclonal antibodies, for example, have been developed to fight certain types of cancer. Monoclonal means the antibodies have been cloned from a single, ancestral cell.

If the antibodies block the coronavirus from binding to cells, it might reduce the viral load carried by an individual, Brantly said. The infective form of a virus outside a cell is called a virion.

“What happens is that a virus gets into our cells, and then those cells are co-opted and so they make lots more virions,” he said. “Then the cell explodes, releasing more virions. If you inhibit the virus getting in cells, then you decrease the number of virus particles in the host.”

And that, it is hoped, improves patient outcomes.

Preliminary evidence in an earlier, smaller trial indicates the patients who might benefit the most from Regeneron’s monoclonal antibodies are those whose bodies have not yet mounted their own antibody defense.

“It is possible it is more helpful in people who have not mounted their own immune response,” Brantly said. “But this is very preliminary evidence that needs to be confirmed.”

He expects the trial to continue through the fall. But if the U.S. Food and Drug Administration grants Regeneron emergency use authorization for the drug, that could complicate things as it might make it more difficult to enroll patients. Patients could receive the drug without being in a trial.

Brantly said he and his team are continually inspired to do their best work to support the UF Health caregivers who are doing so much to help COVID-19 patients.

“Our nurses and doctors who take care of these patients are the honest-to-God heroes,” he said. “I have the greatest admiration for my colleagues who are on the front lines every day.”

This story originally appeared on UF Health.

Check out more stories about UF research on COVID-19.