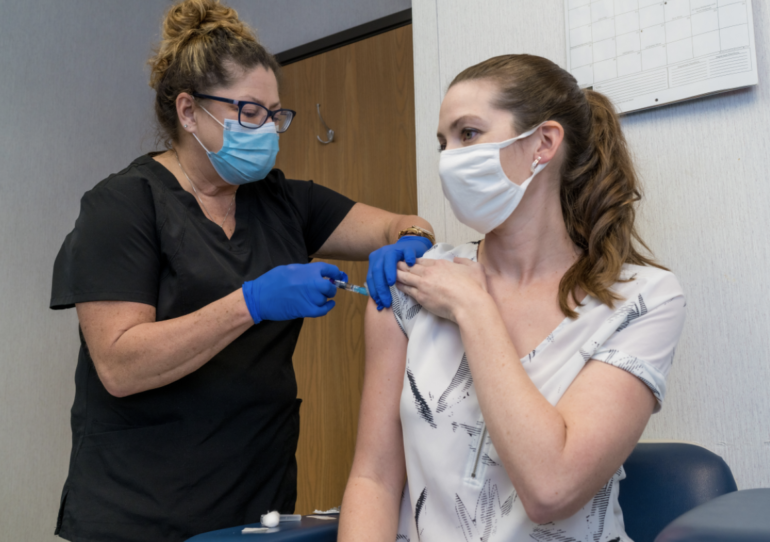

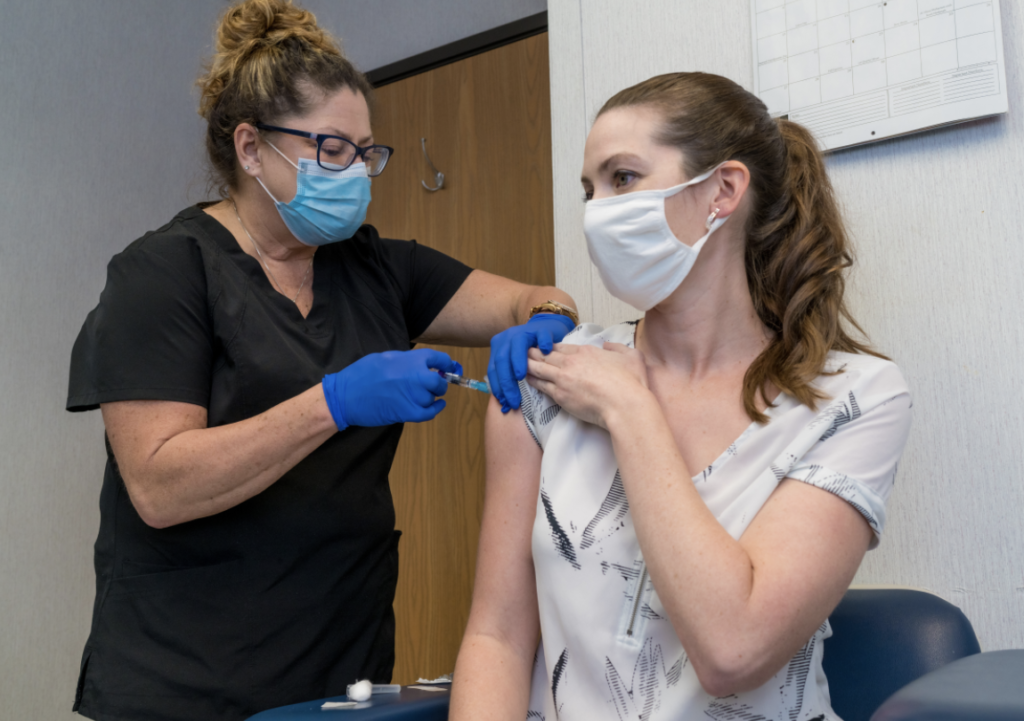

A flu vaccination might do more than protect against influenza. It might also shield some people from a severe case of COVID-19 — even though the infection is caused by an entirely different virus.

People who received a flu vaccination in the year before testing positive for the novel coronavirus were nearly two-and-a-half times less likely to be hospitalized for COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, than those who were unvaccinated, an analysis of patient data by University of Florida Health researchers has found.

And those with a flu vaccination were more than three times less likely to be admitted to an intensive care unit. The effect could be the result of a general priming of the immune system that boosts the body’s readiness to attack, no matter the invader.

“This would actually be a pretty easy way of keeping some people out of the hospital and out of the ICU,” said Arch G. Mainous III, Ph.D., the study’s senior author and a professor in the department of health services research, management and policy at the UF College of Public Health and Health Professions.

The study, which the researchers believe is the first peer-reviewed investigation to document this protective effect, examined de-identified information for the 2,000 patients at UF Health who tested positive for COVID-19 between March and August.

The researchers said more investigation is needed to confirm this association. They said it is important to note the limitations of their work, including that it involved just one medical center. So, it’s unclear if results would also be seen in patients across the nation. Additionally, the number of vaccinated patients in the group studied is relatively low — 10.7% of the total, or 214 people. However, all of the data, including COVID-19 tests, hospitalizations, ICU admissions and influenza vaccination status, come from the patients’ electronic health record and not surveys of patients.

Numbers were adjusted for age, ethnicity and comorbidities, such as diabetes, obesity and other chronic illnesses that can increase the severity of COVID-19.

“We think this gives people a huge incentive to get a vaccination. It’s a double-win in many ways because the vaccination is, of course, helping protect you from influenza as well,” said Mainous, also vice chair for research in the UF College of Medicine’s department of community health and family medicine.

Nothing in the study, however, should be construed as suggesting COVID-19 is identical to flu — COVID-19 is still more lethal than influenza and a far more serious public health concern, Mainous said.

The lead author of the study, published today in the Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, is Ming-Jim Yang, M.D., a third-year resident in family medicine at UF Health.

“People who were vaccinated seem to be more protected,” Yang said. “Many of them seem to be able to avoid hospitalization. And when they are hospitalized, fewer of them are being upgraded to the intensive care unit. We were pleasantly surprised by the results.”

Mainous and Yang said the findings potentially have important implications for defending patients against a disease with few proven effective treatments.

Yang noted this protective effect appears to be present even in the absence of actual flu infection. Why the vaccination might benefit COVID-19 patients remains unclear.

“Honestly, we don’t know why,” said Mainous. “There are a number of ideas out there. And obviously, our study doesn’t point to a specific mechanism.”

One thought is that the flu vaccine essentially primes the body’s natural killer cells, which are part of the immune system. They can target tumors or virally infected cells, containing infections while the immune system’s other defenses are called into action to destroy a pathogenic invader.

If the natural killer cell levels increase because of vaccination, they could presumably mount an attack on infections other than influenza, Yang said.

Scientists “have shown in a couple of other studies that natural killer cell quantities in the lungs are decreased when you’re infected with COVID-19, especially if you have moderate to severe disease,” Yang said.

So, he said, anything that enhances natural killer cell numbers could be beneficial to COVID-19 patients.

Another theory is that components added to the flu vaccine to make it more effective — called adjuncts — heighten the body’s immune response generally. Previous research, Yang said, shows that vaccines with specific adjuncts might have offered protection to those infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, an earlier, less-deadly coronavirus infection first identified in 2003.

Regardless of the mechanism, Mainous said, the patient data are clear.

“The effect is there,” he said. “And it’s very, very strong.”

Mainous and Yang said their research group also will continue to look at whether other types of vaccinations offer the same benefit, particularly the pneumococcal, or pneumonia vaccine, which typically is administered to older patients.

Mainous said he hopes the study will spur people to get their flu vaccinations, especially with the influenza season quickly approaching. A majority of Americans, he said, don’t get their flu vaccinations.

“One of the biggest problems we have with any preventive measure is getting people to do it,” Mainous said. “So, maybe this would be a pretty good push for people to go out and get their flu shot.”

Media contact: Ken Garcia at kdgarcia@ufl.edu or 352-273-9799.

This story originally appeared on UF Health.

Check out more stories about UF research on COVID-19.