Even though President Donald Trump is back at the White House following his hospitalization for COVID-19, people around the world are watching his health, in addition to that of a number of other politicians who have tested positive for the disease. Infectious disease specialist and physician Kartikeya Cherabuddi, who has treated COVID-19 patients, explains what medical doctors monitor and how they treat patients, from the early days after an infection and the critical days that follow.

Early symptoms and when to seek medical help

Common early symptoms include those of the upper respiratory tract – sore throat, runny nose, cough – as well musculoskeletal symptoms, such as as muscle aches, joint pain and fatigue, as well as vomiting and additionally the loss of smell or taste. Fever is present in only a few patients. Many patients may have very mild or no symptoms.

As the illness progresses, doctors monitor the lungs for sympto

ms, such as shortness of breath, or other organ-related problems, such as chest pain of cardiac origin. They sometimes observe confusion, extreme fatigue and weakness in the elderly.

Difficulty breathing or the sensation of being out of breath, new confusion or the inability to stay awake, chest pressure or pain are reasons for being evaluated and for possible hospitalization. Monitoring body temperature is not as helpful for evaluating whether one needs to be hospitalized but a pulse oximeter, which measures your blood oxygen level, can be quite helpful. The higher your risk for severe disease, the lower the threshold should be for being evaluated.

In addition to knowing symptoms, it’s a good idea to have a COVID-19 plan for all members of your family. Here’s how to start:

- Where and how will you seek care?

- Who will care for your dependents, including pets?

- If living alone, who can check on you by phone?

Watching for a second wave after the first week

Symptoms may worsen initially as they progress from the upper respiratory tract to the lungs. A second wave of worsening symptoms can then happen after the first week (often day 8 to 10) of illness, when the immune response goes into overdrive.

In high-risk individuals, it is important during this period after the first week to monitor the patient and to avoid a false sense of security.

Worsening shortness of breath, rapid breathing, the use of additional muscles to breathe, difficulty in getting sufficient oxygen and the appearance of being unwell are some of the signs practitioners watch for. A breathing rate above 30-per-minute or a low oxygen level with a new requirement for supplemental oxygen is classified as severe COVID-19.

Why the immune system response is critical

During early onset of infection, a person’s immune system kicks in with a broad, nonspecific response to the virus, which is especially effective in kids. Immune system proteins called interferons appear to control the infection. The immune cells that attack seasonal coronaviruses which cause common colds do not appear to control the infection but may limit disease severity, duration or both.

From days 5 to 14 after infection, a person’s adaptive immunity, which is specific and targeted to SARS-COV-2, takes over. It involves three components – antibodies, killer and helper T-cells. This response needs to be coordinated and controlled. This is often not the case in the elderly, and could explain the more severe illness that is seen in older individuals. Antibodies can eliminate, or neutralize, the virus.

These immune cells and their products – cytokines, interleukins and interferons – can control infection but in severe cases go out of control. This produces a severe imbalance and causes the cytokine “storm” in adults or the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children.

Doctors carefully follow the patient’s symptoms, exam findings and clinical and laboratory parameters, such as blood tests that measure levels of specific proteins to determine if the patient’s immune system is over-reacting. Critical illness due to COVID-19 develops in 5% of all patients but occurs in 1 in 5 individuals requiring hospitalization.

Levels of treatment – mild to severe

For people who test positive for COVID-19 but are asymptomatic or have mild symptoms, there is no proven, effective therapy. Getting a good night’s sleep and exercise and limiting anxiety are helpful. It is recommended that you maintain physical separation but stay in touch with family or friends. Taking vitamin D could provide some benefit, and has been shown in one metanalysis of studies to protect against acute respiratory infections. Those with very low vitamin D levels benefited the most.

For people with mild to moderate symptoms, monitoring for any symptoms or signs of worsening in addition to pulse oximeter readings is recommended. Blood oxygen levels should be 94% or over in those with no underlying lung disease. If able, you can walk a little and repeat pulse oximetry, gradually increasing to 6 minutes of walking.

For people with severe disease who are hospitalized, there are a number of therapies available:

- Antiviral agents. Remdesivir has been shown to decrease the duration of hospitalization.

- Immunosuppressive agents. Corticosteroids, such as dexamethasone have a broad effect in damping down the immune system and have been shown to reduce the number of deaths from COVID-19 if oxygen is required.

- Oxygen. It is administered to keep oxygen saturation above 94%.

- Medications to prevent blood clots. These medications are given for preventing blood clots during hospitalization. Individual risk and mobility is considered by physicians when used post-discharge.

- Convalescent plasma. Plasma – the liquid portion of blood – from people who have had COVID-19 contains antibodies that can lessen the severity of an infection or prevent a current patient from getting ill. It is primarily available through clinical trials, which are needed to understand it better.

- Monoclonal antibodies. These laboratory-manufactured antibodies, which are now going through clinical trials, could similarly lessen the severity of the disease or shorten the course of the illness.

Lingering effects and ‘long haulers’

Doctors have known that viral infections, including measles, can cause long-term symptoms. Forty percent of survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, which was also caused by a coronavirus, have reported having residual effects even 3.5 years later.

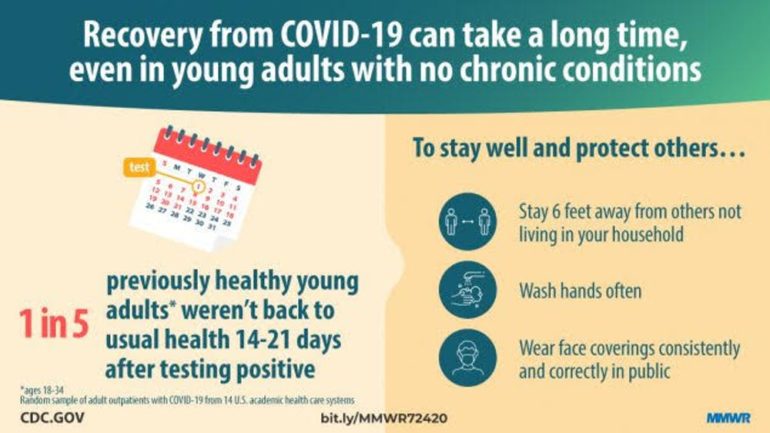

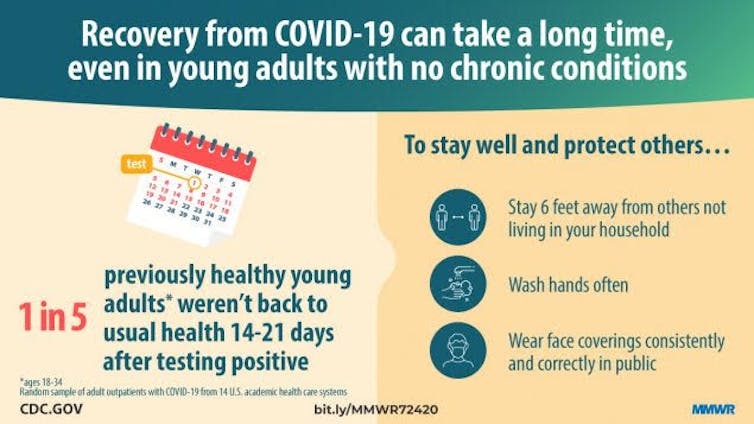

Persistent symptoms for COVID-19 sufferers, termed “long haulers,” sometimes occur even in young adults and children with no underlying medical conditions. In a telephone survey of symptomatic adults who were never hospitalized, 1 in 3 people overall and 1 in 5 among those aged 18 to 34 had not returned to their usual health 14 to 21 days after testing. Symptoms that persist include fatigue, cough, shortness of breath, loss of taste or smell, headache and body aches. Individuals with severe illness requiring hospitalization may take up to six weeks to recover.

Blood clots in the lung, brain and other areas have been reported but with a wide variable range of estimates. Sicker patients and those with more underlying risk factors have a higher incidence. These blood clots – in addition to viral and immune damage to the lungs, heart and brain – can lead to prolonged ill health, decreased mobility and mental issues. A practical and useful guide to rehabilitation self-management after COVID-19 related illness is available from the World Health Organization.

[Get facts about coronavirus and the latest research. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Long-term mental effects are an area of tremendous concern. Doctor offices should perform follow-up phone calls, establish post-COVID-19 clinics, and make mental health resources available. Patients and family members can monitor breathing, exercise tolerance, swelling of limbs, body weight and mental activity, and be on the lookout for signs of depression.

For an individual patient, the course of illness and complications both immediate and long-term are unpredictable. They need to be closely monitored for two weeks following diagnosis for the second wave of worsening and for up to six weeks for recovery if hospitalized with severe illness.

This story originally appeared on The Conversation.

Check out more stories about UF research on COVID-19.