A protein thought to be the novel coronavirus’ entryway into the body could not be detected in the insulin-producing cells of the pancreas in three dozen individuals, the strongest evidence yet that COVID-19 is unlikely to trigger or worsen Type 1 diabetes, according to a new study co-authored by University of Florida researchers.

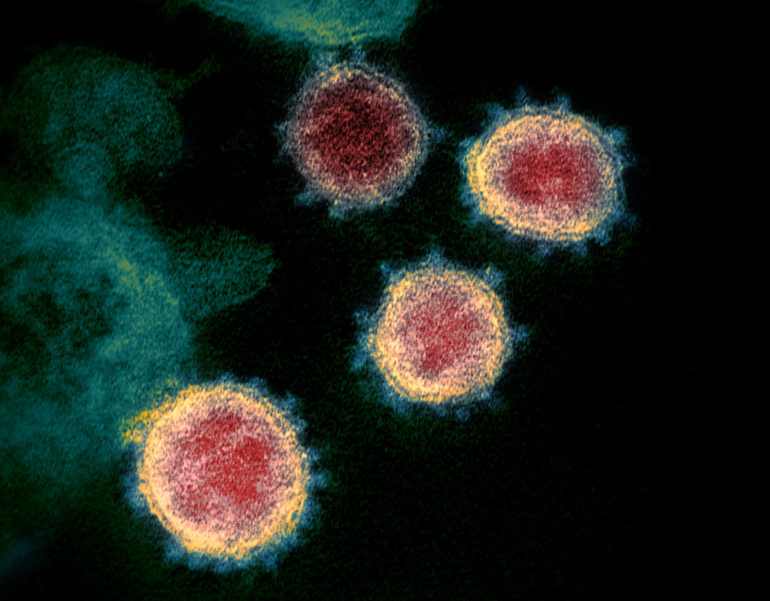

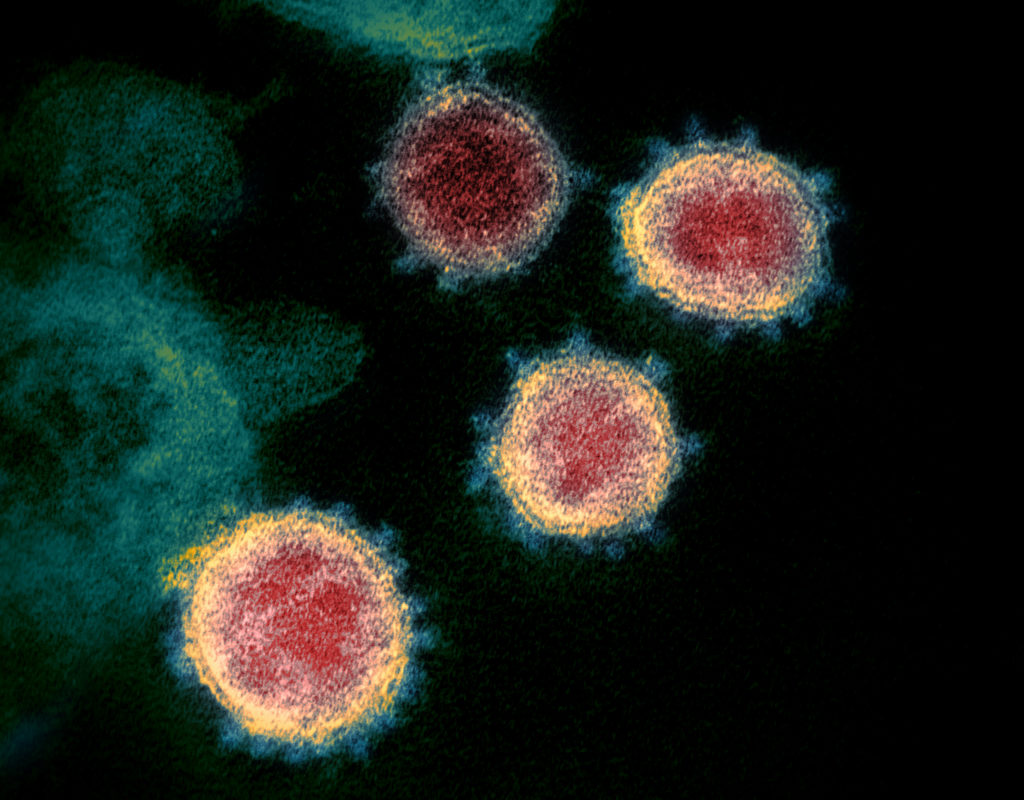

Electronic microscope image of the novel coronavirus isolated from a patient. The virus is shown emerging from the surface of cells cultured in the laboratory. (Photo by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases – Rocky Mountain Laboratories)

The study, involving the UF Diabetes Institute, is not yet peer-reviewed, and its scientists caution that more research is required to understand how the coronavirus might impact insulin-producing beta cells.

Even so, senior author Mark Atkinson, Ph.D., director of the UF Diabetes Institute, believes the work poses a serious challenge to the argument of a causal relationship between COVID-19 and diabetes.

“This does not provide support to the notion that you’re going to develop diabetes because the coronavirus goes in and destroys an individual’s insulin-producing cells,” said Atkinson, who is one of the world’s leading researchers of Type 1 diabetes.

The study was published late Monday as a “preprint” on the website bioRxiv.org. This is one of several online publishers of scientific manuscripts that have not yet appeared in journals. These preprint sites allow scientists to quickly distribute research, an important consideration in a fast-moving pandemic, albeit with the caveat that results are not yet peer-reviewed.

Carmella Evans-Molina, M.D., Ph.D., a co-author of the study and director of the Indiana University Center for Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases, said, “In late spring, there were some early reports suggesting a potential link between COVID-19 and Type 1 diabetes. We felt that it was important to get to the bottom of this.”

In response, researchers launched a multi-institutional effort that included diabetes investigators from UF Health, Indiana University, the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Louisiana State University, the University of Miami and Baylor College of Medicine.

UF Health was instrumental in launching the study. UF Health’s work with diabetes has been nationally recognized, with its diabetes and endocrinology speciality ranked 34th in the 2020-21 national survey of hospitals by U.S. News & World Report.

The idea that there might be a viral trigger to diabetes is not new. Indeed, scientists have reported that enterovirus, a different type of virus than the coronavirus, has been associated with an increase risk of Type 1 diabetes.

A minor Chinese study from a decade ago reported that researchers detected the ACE2 receptor in the beta cells of the pancreas. ACE2 is believed to be the doorway through which the coronavirus invades healthy cells. ACE2 molecules, for example, are found in the lungs and kidneys.

That finding lent support to the idea that beta cells could be infected and destroyed by the coronavirus, reducing the body’s ability to produce insulin and leading to Type 1 diabetes. That also might have an impact on Type 2 diabetes.

But researchers in the current study noted that this earlier work relied on samples from just one individual and used an unspecified chemical reagent to detect ACE2, two glaring weaknesses, making it impossible to directly replicate the work.

The new study, Atkinson said, is the most comprehensive examination yet of the expression of the ACE2 receptor in human pancreatic tissue.

The study examined pancreatic donor samples from 36 non-diabetic individuals who did not have COVID-19. The samples were obtained from nPOD, the Network for Pancreatic Organ donors with Diabetes, which is the world’s largest biobank of pancreatic tissue for studies of diabetes.

The tissue bank, housed at UF Health, has been transformational in the study of Type 1 diabetes, and its pancreatic tissues have been used in more than 248 studies by researchers in 21 countries.

Atkinson said researchers could not detect ACE2 in the insulin-producing beta cells in any of these samples from 36 “normal” individuals ranging in age from neonates to the elderly.

Evans-Molina, who serves as a co-executive director of nPOD with Atkinson, said, “a major strength of our study is that we used several independent methods to test whether ACE2 protein was present in the beta cells, and experiments were performed in multiple labs to make sure our approach was rigorous.”

In addition, the pancreatic tissue of three individuals who died of COVID-19 was examined, and like the other group, the beta cells also did not appear to express ACE2.

However, Atkinson said, ACE2 was found in specialized structures called ducts and small blood vessels of the pancreas in the COVID-19 victims and in the 36 samples from nPOD.

The study also examined the presence of the virus in the pancreas by studying a coronavirus protein in these COVID-19 autopsy-derived tissues. Similar to ACE2, the coronavirus protein — in essence the virus — was exclusively found in the pancreatic ducts, but not the beta cells, in one of these three COVID-19 patients. This patient did not have diabetes.

Coronavirus infection of cells in the pancreatic ducts could still lead to damage of the pancreas in COVID-19 patients. Atkinson noted that the pancreases of COVID-19 patients who have died are also filled with blood clots.

“It’s just like what occurs with many other key organs of the body — in the kidneys, the lungs, just about everywhere,” Atkinson said. “We’re not saying the pancreas is not distorted by COVID-19. But it’s not the insulin-producing cells that appear primarly affected.”

These researchers, however, point to the study’s limitations, among them the fact that pancreatic tissue samples from those who have died from COVID-19 are difficult to obtain despite the prevalence of the disease. Many individuals are not autopsied, and pancreatic tissue quickly degrades when autopsy samples can be found, scientists said. That limits the tissue available for research.

And study authors also note there might be yet another mechanism through which the coronavirus damages beta cells.

“The coronavirus may use a different type of receptor to enter the cell that we don’t know about,” said Irina Kusmartseva, Ph.D., director of nPOD’s Organ Pathology and Processing Core and one of the study’s lead authors.

She said the fact that ACE2 can be found in the small blood vessels, which provide the beta cells with their blood supply, might serve as an indirect means of infection or damage.

Alberto Pugliese, M.D., a researcher at the University of Miami Diabetes Research Institute and co-author of the study, said he believes there is currently insufficient evidence that COVID-19 causes diabetes. But he warned the case is not yet closed.

“Our study does not support that COVID-19 could be a direct trigger by direct infection of the insulin-producing beta cells,” he said. “Do I personally consider this as definitive? No. I think we have to look at a lot more patients and consider alternative ways that the virus could impact diabetes.”

Pugliese, who serves as a co-executive director of nPOD with Atkinson and Evans-Molina, said medical clinics might eventually prove key in establishing whether COVID-19 leads to Type 1 diabetes. Simply put, the number of diagnosed cases of diabetes would be expected to perceptibly rise if that is the case.

Pugliese said much about the coronavirus is yet to be learned.

“Viruses can be tricky,” he said. “They have a lot of different ways of causing havoc, and the way one’s body responds to the virus can sometimes be deleterious.”

This story originally appeared on UF Health.

Check out more stories about UF research on COVID-19.