The leading COVID-19 vaccines aren’t anything like the polio vaccination your grandparents received — or even the flu shot you got this fall. A look under the hood unveils a remarkable advancement in medicine.

The COVID-19 vaccines manufactured by pharmaceutical giants Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna build on a decade’s worth of research into the genetic underpinnings of immunity. They essentially use a piece of the pathogen’s genetic code against it.

These vaccines use an artificial piece of the coronavirus’ genetic instructions to help the body protect itself.

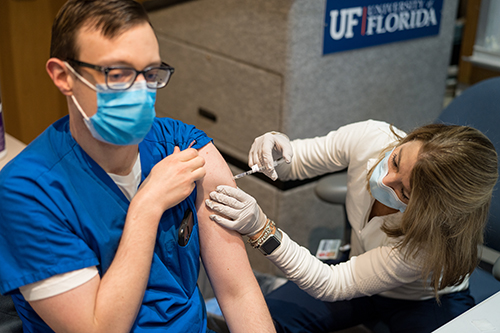

Kartik Cherabuddi, M.D., an associate professor in the University of Florida College of Medicine’s division of infectious diseases and global medicine, is a key player in UF Health’s efforts to vaccinate health care workers who are most at risk of contracting COVID-19 as they treat patients.

Q: Pfizer and Moderna have developed what are known as mRNA vaccines. What is mRNA?

A: Messenger ribonucleic acid, or mRNA, is an essential part of the machinery of life that helps translate the instructions encoded in our DNA, which is found in all our cells, into proteins that actually carry out or express those instructions. If you have to synthesize a protein for a body function, our DNA sort of gets photocopied into the mRNA. The mRNA is sent out of the cell’s nucleus, where it is used to make specific proteins. Among the proteins they can make are those that can help us fight disease.

Q: How do the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines use mRNA?

A: The coronavirus’ famous spike proteins allow the virus to enter and invade, or infect, our cells. These proteins are the key opening the door into our cells. The vaccine’s synthetic mRNA provides the genetic instructions to the cells at the site of injection to produce an important piece of the coronavirus spike protein so that immune cells can recognize the protein and get activated. The vaccine does not transmit live virus, so you can’t get the coronavirus by getting vaccinated.

Synthetic mRNA requires stabilization so it won’t be degraded and destroyed by the immune system before it is taken up by cells. So, the mRNA is packed in lipid nanoparticles that help deliver it straight to the cells. Cold temperatures also help keep it stable.

We’re not interfering with the DNA in the nucleus of our cells or making changes to our genetic encyclopedia. We’re instead introducing this photocopy straight into the cells of our body, so it can be used to produce this specific part of the spike protein. This mRNA degrades and does not stay long-term.

Q: How does that confer protection against the coronavirus?

A: Your cells take up the vaccine with the mRNA and assemble the spike proteins, and then your immune cells recognize the protein as something that’s foreign. This is sort of replicating the infection by using a narrow but critical part of the virus pathway. Your immune system creates antibodies against the spike proteins introduced by the vaccines, conferring protection against future infection by the full coronavirus.

Q: Why is a second shot necessary about 17 to 21 days later for the Pfizer vaccine and about 28 days later for Moderna’s?

A: Moderna and Pfizer saw in their initial studies that a single dose didn’t produce as much of an immune response as necessary. Most vaccines are given as a series of shots. In general, we know the first shot primes the immune cells. The second shot really gears them into action, so you obtain adequate protection. For these vaccines, the effectiveness is only 50% with one dose, but goes up to greater than 90% with the second dose.

Q: What are the side effects of these vaccines?

A: The first potential side effect is at the site of the shot itself, an infusion site reaction. It can cause a sore arm, similar to what you would have experienced with flu shots, or tetanus shots.

In some people, it can cause a flu-like illness after either the initial or second shot — a little more with the second shot than with the first. The second shot activates more of the immune system, so you could have a moderate flu-like illness — fever, fatigue, chills and body aches. The symptoms usually go away in 24 hours.

It is important to emphasize that the vaccines have been shown in trials to be extremely safe.

Q: How effective are these vaccines in preventing COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus?

A: The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines have been shown in trials to be about 95% and 94% effective, respectively, in preventing symptomatic and severe illness. The efficacy numbers make it incredibly good. You’re not going through this all for nothing, right? There’re very few things in medicine that are 95% effective. Extremely few.

Q: How long will the vaccines protect us?

A: We know for some viruses, measles and rubella, for example, that a vaccine offers protection for many years. On the other extreme is the influenza vaccine, where we have to get vaccinated every year. These mRNA vaccines may fall somewhere in between. We’ll have more information about the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines in the coming months and be better able to predict long-term immunity.

This story originally appeared on UF Health.

Check out stories about UF research on COVID-19.